In March 2023, the government offered teachers in England higher salary increases, as well as extra grant funding for schools. The salary rises and extra funding were rejected by teaching unions as being insufficient. As a result, there is ongoing industrial action in schools and continued debate on teacher salaries. In this article, we seek to describe the offer made by the government and how it affects the long-term changes to teacher pay in England over time.

In short, our analysis comes to three main conclusions:

- The offer of higher salaries is only part-funded. The government has offered to pay the full cost of a one-off £1,000 bonus, but it will only pay half the cost of an extra 1% on pay settlements. Schools will need to fund the other half from existing budgets.

- The higher salary offer is still, on average, affordable for schools. Even with the higher teacher pay offer, we still expect total school funding to be growing faster than costs for most schools this year and next.

- The underlying position on school funding and teacher pay is basically unchanged. School funding will still be about the same level in real-terms in 2024 as it was in 2010, and most teacher salaries in 2023 will be about 12% lower in real-terms than in 2010.

What have teachers in England been offered?

In September 2022, most teacher salaries were increased by 5%. New and inexperienced teachers received higher increases of up to 9%, on the way to delivering a government commitment of teacher starting salaries of £30,000 in England by 2024. These increases were in line with the recommendations of the School Teachers' Review Body (STRB). These changes represented some of the biggest cash-terms increases in teacher salaries for over 15 years. However, with CPIH inflation (i.e. CPI including owner-occupied housing costs) running at 9% in 2022–23, these increases will still represent real-terms salary cuts for the vast majority of teachers.

As part of its higher offer in March 2023, the government offered teachers in England an extra non-consolidated payment of £1,000 for the 2022–23 academic year. This represents over 3% of existing teacher salaries for new and inexperienced teachers, down to about 2% for more experienced teachers. This part of the package was fully funded with £530m of extra grant funding to schools to cover the cost.

For September 2023, the government had very recently assumed that an average offer of 3.5% was affordable for schools within existing budgets (as set out in the government’s evidence to the STRB published at the end of February 2023). In its updated offer to teachers, the government instead proposed a higher average teacher pay offer of 4.5%, comprised of 4.3% for most teachers and the planned higher increases for new and inexperienced teachers.

This effectively represents an extra 1% on previously assumed pay awards for teachers for September 2023. The cost to schools of an extra 1% over a full year is around £300m (based on the government’s evidence to the STRB). The government has so far offered schools an extra £150m in grant funding over a full year. In this sense, the government has offered to cover about half of the cost, with schools expected to cover the other half, or about £150m, from their existing budgets.

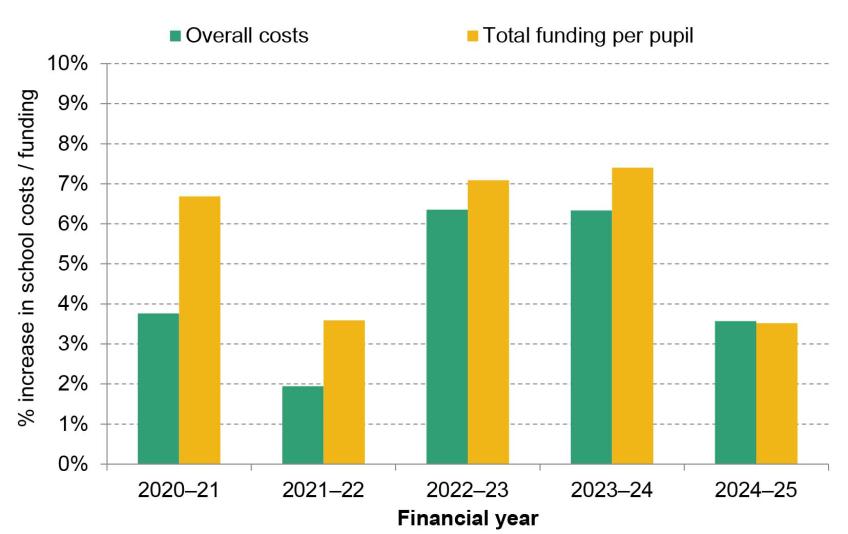

The government has assumed that lower-than-expected energy prices mean that schools can afford to cover this extra £150m. This is not an unreasonable assumption. Indeed, Figure 1 shows that we currently expect total funding to grow by slightly more than estimated costs in 2023–24, even with the higher teacher pay offer. However, this is still a tight picture, with school funding growing by only 1% more than total costs in 2023–24. This is also an average picture. There will be many schools receiving lower than average funding increases, e.g., schools in London, and some schools will be seeing faster than average cost rises, e.g., special schools that employ more support staff and schools in London that rely more on less experienced teachers.

Figure 1. Estimated increases in funding and school costs over time

Source: Updated version of Figure 2, ‘School spending and costs: the coming crunch’, Luke Sibieta, IFS Briefing Note BN347

The debate on whether the offer is fully funded is also a bit of a distraction from the wider picture. The £150m cost of making a fully funded offer is essentially a rounding error on public sector spending figures. The extra 0.5% on teacher pay awards to be found within existing school budgets only comprises about 0.25% of annual school spending.

The provision of an extra £150m also would not really have that much effect on underlying school finances. We would still be expecting total school funding per pupil to return to about 2010 levels by 2024. This equates to a 14-year period with no overall real-terms growth in school funding per pupil, a significant squeeze on school resources in historical terms.

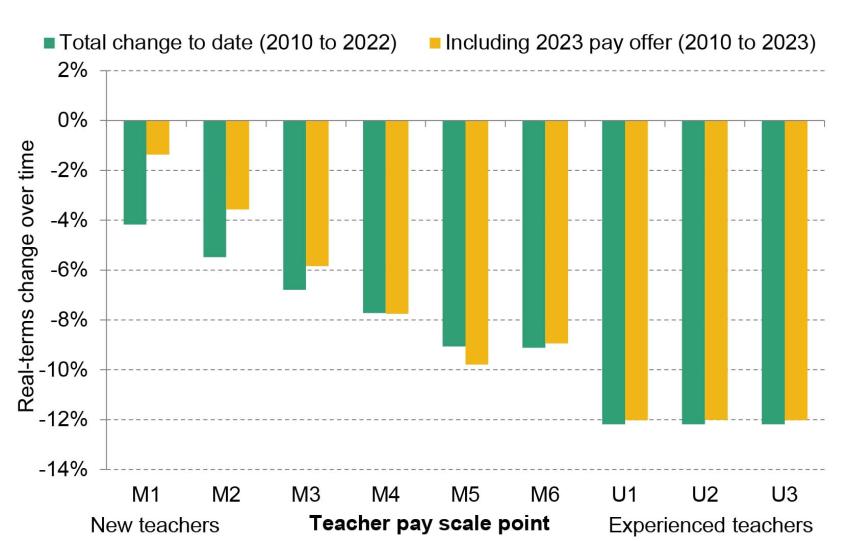

The pay offer also would not have much effect on the long-run picture of real-terms cuts to teacher salaries back to 2010. Figure 2 shows the changes in core teacher salaries to date between 2010 and 2022, and then up to 2023 (including the updated teacher pay offer). Salaries for more experienced teachers on the upper pay scale fell by 12% in real-terms between 2010 and 2022, which accounts for over 50% of teachers. Salaries for new and less experienced teachers fell by less, with starting salaries falling by 4% in real-terms. This equates to an average decline of about 10% between 2010 and 2022.

These declines are smaller than we have previously published. This is because we are now able to account for a full financial year of actual CPIH inflation in 2022–23, which has turned out to be about 9%. We were previously using forecasts for overall CPI inflation of 10%, which excludes the changing cost of owner-occupied housing.

Looking to 2023, we still see that salaries for more experienced teachers are due to be about 12% lower than in 2010. Because of faster growth at the bottom of the pay scale, starting salaries would be nearly back to 2010 levels in real-terms. However, average salaries across the pay scale would still be more than 9% lower in 2010.

Figure 2. Real-terms changes over time in teacher core salary points since 2010: actual and proposed

Note and source: Years refer to financial years starting each April. Teacher pay scales taken from School Teachers' Pay and Conditions Document 2010 (https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/school-teachers-pay-and-conditions) and proposed scales from STRB report: 2022 (https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/school-teachers-review-body-32nd-report-2022). Real-terms value calculated based on average value of CPIH index (https://www.ons.gov.uk/datasets/cpih01/editions/time-series/versions/33) in the relevant financial year (e.g. 2014–15 for September 2014).