Reporting in The Times yesterday suggests the Chancellor is considering cutting the headline rate of inheritance tax from 40% to 30% or even 20%, with rumours of a pledge to abolish the tax eventually. Cutting or abolishing inheritance tax would come at a growing fiscal cost, with over four-fifths of the gains from any reduction in the tax rate going to those with over £1 million at death. While any tax cut will add something to inflationary pressure, the inflation effect of cutting inheritance tax is likely smaller than for most other tax cuts given that the beneficiaries will be relatively well-off and more likely to save the proceeds of the tax cut.

Inheritance tax raises £7 billion per annum today and by 2032–33 we forecast that this will reach £15 billion. This rise is because of increasing levels of wealth held by those at older ages. At 0.5% of GDP in 2032–33, inheritance tax revenues will remain modest in the grand scheme of the public finances, but any cuts in the rate of inheritance tax would nonetheless require lower spending or higher taxes elsewhere, or a larger deficit. To put things into context, reducing the inheritance tax rate to 20% would roughly offset the cut in benefit spending that would be achieved by uprating benefits by October’s rather than September’s rate of inflation (as is also rumoured to be under consideration).

A small but growing fraction of the population would benefit from cuts to inheritance tax. In the most recent HMRC data, less than 4% of deaths resulted in inheritance tax being paid. But that is set to rise to over 7%, or over 50,000 people per year, over the next decade. Further, the first member of a married or civil-partnered couple to die will often pass their wealth on to their spouse inheritance-tax-free. They might still be seen as affected by the tax if their surviving partner then pays inheritance tax at their death. Counting both members of such couples as taxpayers gets us to one in eight (12%) paying inheritance tax in 2032–33.

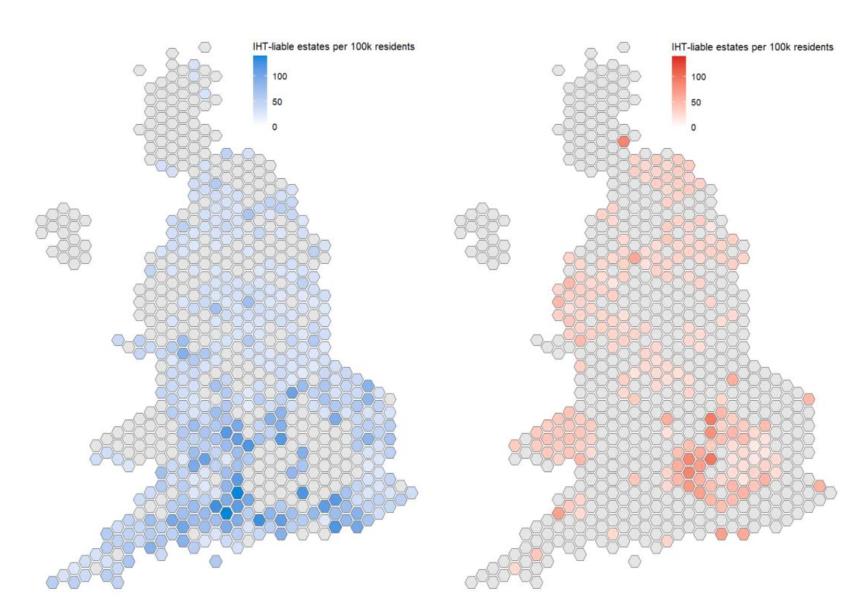

This is geographically concentrated, with around one in six paying the tax in London, over twice the national average and eight times higher than in the North East. Figure 1 shows this concentration at the parliamentary constituency level. The largest benefits are in the ‘Home Counties’ seats, which largely voted Conservative in 2019 (Figure 1a). Labour-supporting seats in the North and West of London, and in Edinburgh, would also benefit (Figure 1b).

Figure 1. Number of inheritance-tax-liable estates per 100,000 residents, by parliamentary constituency and 2019 election outcomes (for the two largest parties)

(a) Conservative seats, 2019 election (b) Labour seats, 2019 election

Source: Authors’ calculations using table 12.9 of HM Revenue and Customs (2023).

Figure 2 shows that the fiscal benefits of a tax cut or abolition would be concentrated among the wealthiest. If inheritance tax were cut or abolished in 2024–25, 83% of the fiscal benefit would go to the wealthiest 5%. These people have over £1 million at the time of their death and would each be able to pass on £180,000 more after tax on average if the inheritance tax rate were cut to 20%. There would be no benefit at all to the more than 90% of individuals who would anyway not pay inheritance tax because their wealth is below the tax-free threshold. The top 1% would gain £500,000 on average if the inheritance tax rate were halved.

Figure 2. Average benefit from reducing inheritance tax to 20% (LHS) and share of overall tax reduction received (RHS), by wealth ventile of donor

Note: Each ventile is 5% of the distribution of those dying, ordered by wealth bequeathed. We exclude the first member of married and civil-partnered couples to die, who are assumed to pass all wealth to their partner at death. For details of methodology, see Advani and Sturrock (2023). Values in 2023–24 prices.

Source: Authors’ calculations using the Wealth and Assets Survey.

We can also view the benefits from the side of those receiving inheritances. Among those born in the 1970s and early 1980s, those who attended university were more than 10 times more likely to have parents in the wealthiest fifth than those who had only up to compulsory levels of education. Almost all inheritance tax is paid by those with parents in the wealthiest fifth. Therefore, we would expect that in the coming years and decades, as a whole, graduates would gain around 10 times more from any cut to inheritance tax than those with only up to GCSEs or equivalent. Someone in the top fifth of earners is eight times more likely to have a parent in the top fifth by wealth – and therefore to benefit from an inheritance tax cut – than someone in the bottom fifth of earners.

At present, the UK has a high headline inheritance tax rate by international standards and cutting it to 30% or even 20% would make it more similar to those in some other European countries. However, it is a mistake to look only at the headline rate. The UK also has a high tax-free exemption by international standards and therefore a relatively low level of inheritance tax payers. There are also a range of exemptions within the inheritance tax system which mean that those with estates worth £3–£5 million pay an inheritance tax rate of only around 25% and this actually falls to 17% for estates worth over £10 million. Halving the inheritance tax rate would reduce this further, giving an effective rate of less than 10% for estates worth over £10 million.

If the Chancellor wishes to cut the rate of inheritance tax, it should be used as an opportunity to also improve the system. Capping reliefs for business and agricultural assets at £500,000 per person and bringing pension pots into the scope of inheritance tax would rationalise the system. Combining this with a cut in the inheritance tax rate from 40% to 30% for estates worth up to £2 million would be roughly revenue-neutral. This would make the system fairer and shift the burden of inheritance taxation towards the largest estates.

There are reasonable arguments for and against inheritance tax, but no getting away from the fact that scrapping it comes with a sizeable and growing price tag and benefits the wealthiest the most. Halving the rate would reduce the tax on the biggest 5% of estates at death by an average of £180,000, while more than 90% are already not subject to any inheritance tax and therefore would not benefit.