Today the Scottish Government released the latest version of Government Expenditure and Revenue Scotland (GERS) covering 2015–16. In this observation we discuss what we can learn about Scotland’s fiscal position from these figures. The main finding is that further declines in revenues and output from the North Sea oil and gas sector pushed up Scotland’s budget deficit a little – at the same time the deficit continued to shrink in the UK as a whole.

Today’s estimates

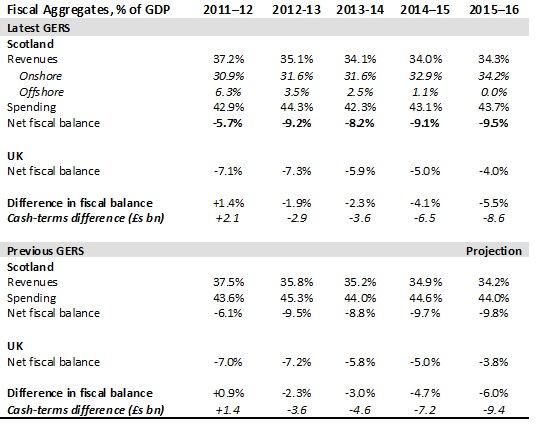

Table 1 shows figures for revenues, spending, and the net fiscal balance (i.e. the budget deficit or surplus) for Scotland for each year between 2011–12 and 2015–16, measured as a percentage of national income. It also shows the net fiscal balance for the UK as a whole, and the ‘fiscal gap’ between Scotland and the UK. The top panel shows estimates from the most recent GERS publication. The bottom panel shows estimates from the previous edition of GERS and projections we made for 2015–16 earlier this year.

Table 1: Fiscal aggregates, UK and Scotland, 2011–12 to 2015–16

Looking at the most recent estimates from the top panel, the first thing to note is that the Scottish budget deficit widened from 9.1% of national income in 2014–15 to 9.5% in 2015–16. This is in contrast to the picture for the UK as a whole where the deficit fell from 5.0% to 4.0%. The fiscal gap – i.e. how much larger Scotland’s deficit is than the deficit of the UK as a whole – therefore increased from 4.1% of national income (£6.5 billion) to 5.5% of national income (£8.6 billion).

What explains these differences?

It is not what happened on land. ‘Onshore revenues’ (i.e. revenues other than from taxes on North Sea oil and gas) grew at a very similar rate in cash terms in Scotland (3.7%) as in the UK as a whole (3.8%). Similarly, public expenditure rose at a very similar rate (1.0% as opposed to 0.9%). The Scottish ‘onshore deficit’ therefore actually shrank by a similar magnitude (1 percentage point of national income) to that of the UK as a whole.

The divergence in trends is instead explained by what happened out in the North Sea. The fall in the oil price depressed the total value of oil and gas production in the North Sea, which had two effects:

- First, there was a further fall in tax revenues from oil and gas production: estimated as just £60 million in 2015–16 (0.0% of national income) compared with £1.8 billion in 2014–15 (1.1% of national income) and £9.6 billion back in 2011–12 (6.3% of national income). This fall in offshore tax revenues pushed up the cash-terms budget deficit.

- Second, the lower value of oil and gas production put downward pressure on Scottish national income. Indeed, Scottish national income is estimated to have fallen 0.5% in cash terms in 2015–16, compared to an increase of 2.4% for the UK as a whole. Lower national income means that any given cash-terms budget deficit represents a larger proportion of national income.

Taken together these two effects of lower oil prices explain the growing gap between the relative size of Scotland’s budget deficit and that of the UK as a whole.

Comparing the most recent estimates with previous estimates and projections

Comparing the top (most recent GERS) and bottom (previous GERS and projection) panel of the Table we can see that the Scottish budget deficit was slightly lower than we had projected earlier this year: 9.5% of national income as opposed to 9.8%. The fiscal gap between Scotland the UK was also a little lower: 5.5% of national income (£8.6 billion in cash terms) as opposed to 6.0% (£9.4 billion).

These (small) differences reflect revisions to data and methodology in the most recent edition of GERS that also affect estimates for previous years. In particular, estimated public expenditure in Scotland has been revised down by several hundred million pounds in each of the previous four years (2011–12 to 2014–15). Key changes include stripping out expenditure on Crossrail in London (which was previously unidentifiable and therefore allocated to Scotland in proportion to population), and other changes to the “accounting adjustment”. Moves from budget estimates to outturns for Scottish local authority spending also led to a downward revision to spending in 2014–15.

Perhaps an even more important factor has been the upward revision to estimates of Scottish national income since the last edition of GERS was published. For instance, national income is now estimated to have been £156.8 billion in 2014–15 as opposed to £153.3 billion in the last edition of GERS. This means any given cash-terms deficit would be a lower share of (the higher) national income.

This reminds us that the allocation of spending and revenues between Scotland and the rest of the UK is a somewhat imprecise science, and is subject to both data revision and methodological change over time. But these revisions do not detract from the fact that GERS is an important publication that provides a detailed and very valuable picture of Scotland’s underlying public finances. The bringing forward of GERS (the most recent edition was published with around a 5 month as opposed to a 11 month lag) would mean, all else equal, more potential for revisions in future years (a little less data is now available when the figures are first produced). However, the data are now much more timely, so this is probably a (small) price worth paying.

Looking to the future

Looking ahead to 2016–17 and beyond, what can we say? Low oil prices – which are forecasted to persist for some time – are likely to mean continuing weakness in North Sea revenues, although the recent fall in the value of the pound might help a little (as oil is priced in dollars, which are now worth more pounds). This means that Scotland’s implicit deficit is likely to remain substantially greater than that for the UK as a whole – as we projected back in March.

However, there is more uncertainty than usual about just what the path for Scotland’s public finances will look like in the years ahead, given the recent vote to leave the EU. The consensus among economists is that leaving the EU will lead to a weaker economy than would otherwise have been the case, depressing tax revenues and pushing up some areas of spending (like welfare spending). All else equal and without further policy action, this would likely increase budget deficits for both Scotland and the UK in the years ahead above those projected or forecast back in March. Whether this would widen or narrow the gap between Scotland and the UK as a whole would depend on whether Scotland were more or less affected by the impact of the EU vote than the rest of the UK.

Given this uncertainty – and given that it is not yet clear how the UK government will change its fiscal plans in response to any economic slowdown – any projections we made for future years would be subject to wider-than-normal margins of error. For this reason we will await more information on the potential state of the economy, public finances and future fiscal policy before updating our longer-term projections for the Scottish public finances.

The authors would like to thank the ESRC who funded this obervation as part of the public finance observations series.