The Covid-19 pandemic has resulted in postponed or cancelled hospital care for millions of people in England. This is as a result of both the cancellation of non-urgent treatment by hospitals and changes in patient care-seeking behaviour, and has led to rising waiting lists for routine care and concerns over the consequences of missed treatment for patient outcomes. Furthermore, the direct health impacts of Covid-19 have not been spread evenly across population groups. In many countries – including the UK – death and hospitalisation rates from Covid-19 have been higher among some ethnic minorities. If reductions in hospital care are also greater among these groups, this risks further exacerbating existing health inequalities and the direct health consequences of the pandemic.

In a new paper published today in the British Medical Journal: Quality and Safety, researchers from IFS, Imperial College and Harvard University show how the loss of hospital care in England in the first ten months of the pandemic differed by ethnicity. Previous IFS research has shown descriptively that care was not lost equally across different ethnicities during this period: for example, between March and December 2020, there was a 21% reduction in non-Covid emergency admissions of white individuals, but a 28% and 32% reduction for black and Asian individuals respectively. However, these raw differences could be driven by many different factors. If ethnic minority patients are on average younger or less-sick, and hospitals prioritised the sickest patients, the larger reduction in ethnic minority emergency admissions may simply reflect differences in need for care. Similarly, it may be that areas with larger ethnic minority populations also had higher Covid-19 rates and so their local hospitals were under greater pressure and had to cancel more activity, or that patients in these areas were less willing to attend hospitals. The latest research therefore builds on these previous findings by controlling for many factors that differ by the ethnic mix of the local area, including the demographics, medical need, prior hospital usage, socio-economic deprivation and local Covid-19 infection rates of different areas. This allows us to better understand what drove differences in care loss during the pandemic.

Differences by local-area ethnic minority population

In our analysis we split all local areas in England into five groups based on the proportion of their hospital admissions in 2019 that were ethnic minority (non-white) patients. This allows us to compare all local areas in England, but does not allow us to examine the potentially large differences between different ethnic minority groups. We then compare how admissions changed before and after the pandemic for each local area relative to the lowest ethnic minority population group (where only 0.9% of patients are from an ethnic minority), after controlling for differences in local area characteristics and prior usage that may have also influenced the changes in hospital activity.

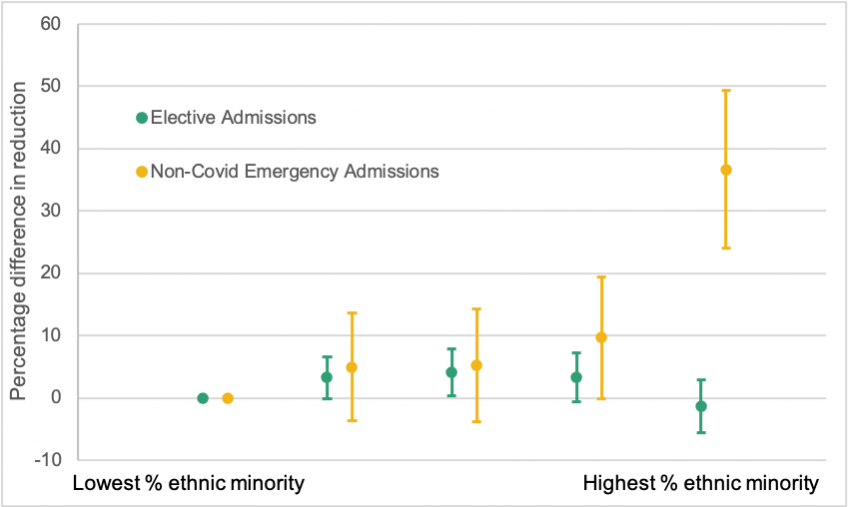

Figure 1. shows the reduction in admissions during the pandemic for each group relative to the lowest ethnic minority population group (the 20% of areas with the highest share of NHS hospital patients who were recorded as white in 2019). In particular, it shows the percentage difference – so a positive number indicates that the group experienced a larger reduction than the lowest ethnicity minority population group. The green series on the graph shows that the areas with the median share of ethnic minority populations experienced slightly larger reductions in elective admissions, while the areas with the largest ethnic minority populations (where 48.1% of patients are from an ethnic minority) experienced reductions approximately equal to those of the areas with the smallest ethnic minority population.

The story is quite different for non-Covid emergency admissions (the orange series). In this case, there is no significant difference between the reductions in the second, third and fourth quintiles. However, there is a 36.7% larger reduction in emergency admissions in the highest ethnic minority population group. We further split emergency admissions into patients with high-severity diagnoses and those with low-severity diagnoses, and find similar inequalities for both types of emergency care.

These results therefore suggest that there was little difference in the reductions of elective admissions by local-area ethnic minority population, but that areas with the highest ethnic minority population experienced much larger reductions in emergency admissions. Note that because we are controlling for other differences in local area characteristics this difference is not driven by the fact that ethnic minorities might live in poorer areas or have different demographics.

Figure 1. Reduction in hospital admissions by ethnic minority population quintile

Note: This shows the percentage difference in reductions in admissions for each ethnic minority quintile relative to the lowest % ethnic minority quintile. This is adjusted for prior usage and controlling for differences in local area demographics, medical need and socio-economic deprivation. Bars show 95% confidence intervals.

Source: Transformed version of Figure 3 of Warner M, Burn S, Stoye G, et al. BMJ Qual Saf 2021

What drives these differences?

There are a number of potential different reasons for these differences in reductions in hospital activity. One potential explanation is that areas with higher shares of ethnic minorities had higher rates of COVID-19 infections or hospitalisation rates, and that potential patients in these areas stayed away (or were told to stay away) from hospitals as a result. However, the results do not substantially change when controlling for different measures of local Covid-19 rates, suggesting that differential Covid-19 infection or hospitalisation rates were not the driving factor behind differences in care loss.

Our results do suggest that these differences were not just driven by changes made by hospitals, such as cancelling activity or raising admission thresholds. Decisions made by hospitals would likely have resulted in similar gradients across ethnicity groups for changes in both emergency and elective admissions: indeed, elective admissions would likely have been more affected since they are often less urgent, and consequently easier and safer for hospitals for postpone. That we find a large difference by ethnicity for emergency admissions but not elective admissions therefore suggests that these differences were, at least in part, driven by changes in patient behaviour. This is consistent with survey evidence that ethnic minorities have been more likely to avoid seeking care during the pandemic.

Unfortunately, we cannot yet distinguish what factors drove these changes in demand for healthcare, and understanding what drove these changes remains an important area of future research. Furthermore, areas with larger shares of ethnic minority patients will have populations from a range of diverse population groups that will have had different experiences of the pandemic, health needs and care-seeking behaviour. This research takes a first step by documenting differences as a whole but further work is required to understand differences in changes to care received across ethnicities, and the drivers of these changes, during the pandemic.

Conclusions

It is not clear what the ultimate consequences of missed care during the Covid-19 pandemic will be, and this remains a priority area for policy and future research. While some of this missed treatment may not have long-lasting consequences for patients, it is likely that health outcomes for many patients (and particularly those with greater needs) will be worse as a result of missed or delayed care. Our results suggest that patients in areas with higher shares of ethnic minority patients have been disproportionately affected by disruption to emergency hospital care during Covid-19, areas which already had worse average health outcomes prior to the pandemic. Addressing these shortfalls in care will therefore likely need additional targeted support to avoid these worsening pre-existing health inequalities.