With no vaccination available, scientists recommend non-pharmaceutical interventions – in particular, handwashing, social distancing, and the shielding of elderly and vulnerable groups – as the only feasible way of suppressing the spread of COVID-19, and lessening its mortality rate. Such measures, when extensively and strictly enforced, appear to have been effective in stemming the spread of the virus in South Korea and China, and there are promising early signs of their effectiveness in Italy too.

These types of measures are particularly important in contexts with fragile health systems – typically observed in Low and Lower-Middle-Income Countries (LICs) – which will swiftly be overwhelmed if the disease spreads beyond a small number of cases.

However, the success of these non-pharmaceutical interventions rests on widespread compliance which could be more difficult to achieve in LICs than in other parts of the world. In particular, as we will set out here, most households living in LICs are likely to face significant challenges in adopting these measures. Many of these challenges are driven by poverty and economic insecurity and include, for example, communal living and lack of handwashing facilities. These difficulties suggest that government policy advocating handwashing, social distancing, and the shielding of the vulnerable may not be effective at suppressing COVID-19, and lessening its impact, in LICs unless accompanied with substantial support to help households comply.

Providing such support is essential to save lives in LICs. It will also benefit citizens of higher-income countries, given that if the disease continues to be endemic anywhere in the world, the likelihood of continued global spread will remain high.

In this note, we highlight some of the challenges households in LICs will face in adopting three preventative measures: (1) washing hands frequently with soap; (2) adopting social distancing measures; and (3) shielding more vulnerable citizens, including the elderly.

Frequent handwashing

Handwashing with soap and water for 20 seconds is effective at reducing the spread of COVID-19. Soap kills the virus, and a large portion of transmission happens when people touch infected surfaces. While most people’s homes and work environments in high-income countries are equipped with handwashing facilities and soap, the same is not true for many people in LICs.

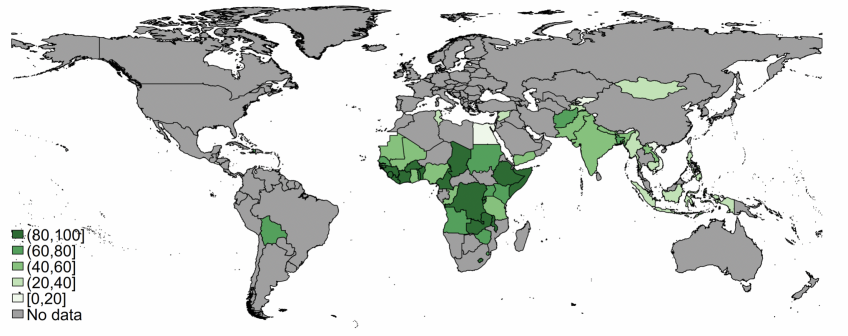

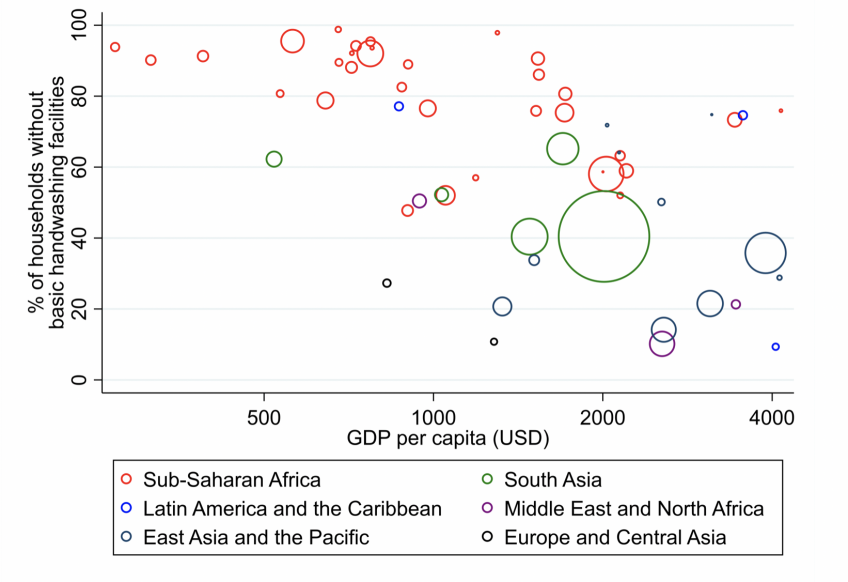

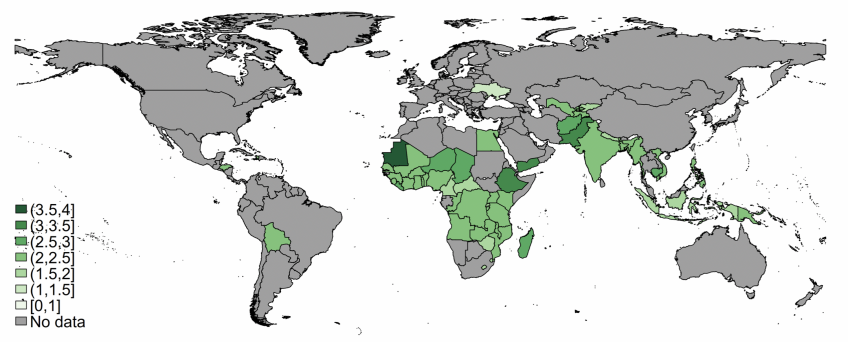

In LICs, just under half (48%) of households do not have handwashing facilities with soap and water in their home.[1][2] Together, the population of these countries is 3.5 billion, implying that for at least 1.7 billion people frequent handwashing with soap will be challenging. Figure 1a shows that households without access to handwashing facilities and soap are concentrated in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia. Figure 1b shows that within the broad category of LICs, there is much variation in access by countries’ income levels. In countries with a GDP per capita per year of less than one thousand US dollars, where half a billion people live, 82.4% of households do not have access to handwashing facilities. In countries with GDP per capita of more than $3,000, this falls to 35.1%.

Figure 1a: Per cent of households without basic handwashing facilities

Note: map shows per cent of households with no soap and water in their household, in LICs with available data. See Data section for data sources.

Figure 1b: Income gradient in households without basic handwashing facilities

Note: graph shows per cent of households with no soap and water in their household against annual GDP per capita (in current USD) in LICs with available data. Marker area is proportional to population. See Data section for data sources.

Social distancing

Social distancing measures aim at reducing interactions between people in order to reduce transmission of COVID-19. Measures include avoiding contact with people displaying symptoms, avoiding gatherings (defined by many countries as more than two people) with friends and family, and working from home.

People who have pre-existing health conditions, are 70 or more years old, or are pregnant are especially urged to follow social distancing advice to “shield” themselves from infection.[3]

Social distancing at home: For many households living in LICs, it will be harder to maintain distance between members due to more crowded living. In LICs, on average, 2.4 people share a room for sleeping.[4] In contrast, in 78% of households in England and Wales, there are at least as many bedrooms as there are household members.[5] The substantially higher rates of overcrowding within households in LICs will bring a greater risk of within-household transmission.

Figure 2: Average number of people per sleeping room

Note: See data section for data sources.

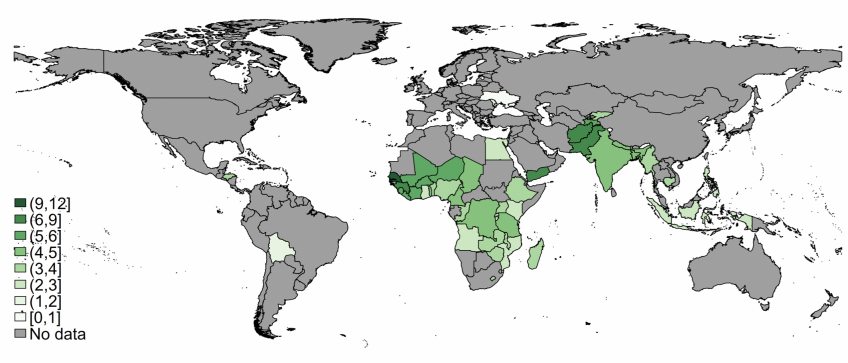

Shielding of Older and More Vulnerable Individuals: Minimising social contact of groups that might be at particularly high risk of death or severe complications is key to reducing the overall mortality rate associated with COVID-19. In addition to general overcrowding, in most LICs, it is far less common for older people to live alone, or exclusively with individuals of a similar age than in wealthy countries. People aged 70 or older in LICs live with an average of 4 individuals below the age of 70 (Figure 3).[6] This is in very stark contrast to the UK, where those aged 70 and over live with an average of just 0.3 people aged below 70.[7] Moreover, 9% of households in LICs contain a pregnant woman, compared to just 2% in the UK.[8] Families living in overcrowded housing where younger members must incur some social contact to satisfy daily necessities will have a harder time shielding older members by limiting their social contact.

Figure 3: Average number of people aged under 70 that those aged 70 and over live with

Note: map presents the average number of 0-69 year olds living in households, conditional on at least one household member being aged 70 or over. See Data section for data sources.

Social distancing outside the home: Most people’s daily routines, including their work, involve close contact with others. Therefore, drastically reducing the rate at which people have contact with one another would require sweeping changes to people’s routines. As in higher-income countries, people with jobs that cannot be done from home or at a distance from others will face particular difficulties in complying with social distancing advice. And those who are self-employed or lack secure contracts may face severe financial difficulties that necessitate a continuation of work, meaning they may continue to come into contact with others. High rates of informality and self-employment in LICs would make social distancing hard for a very large proportion of the population. Further, similarly to the situation of many in higher-income countries, many households in LICs have little to fall back on if they can’t work. For example, only 42% reported having saved money in the past year, and 52% report having no way of finding funds for an emergency.[9] As is currently being implemented in many higher-income countries, large-scale government-funded support to households who cannot work due to the crisis may be the only option to ensure that households are able to practice social distancing without enormous adverse economic consequences. Different forms of support – for example, universal cash transfers, cash transfers targeted at those most affected, or in-kind transfers of essential supplies – will differ in their level of feasibility between LICs depending on, for instance, the existing capacity and scope of social security programs.

Many citizens in LICs face additional challenges in limiting their contacts outside of the household that households in wealthier economies might not even consider. The majority of households in LICs do not own a private toilet or a private water source, and have to leave their house for these necessities. Further, only one-third (32%) of households have a refrigerator, which makes it hard to minimize the frequency of shopping for or collecting food.

Implications

A substantial increase in access to news and media will facilitate access to the latest public health advice. Currently, 84% of households in LICs now have a mobile telephone, and 59% have a television.[10] Relative to a decade ago, increased access to these technologies is an opportunity to provide, even in remote communities, up-to-date and accurate information and advice.

However, as the statistics we present in this brief highlight, getting the message out is unlikely to be sufficient to ensure large-scale behavioural change. For example, for frequent handwashing by the whole population to be an effective mitigation measure, substantial support to improve households’ access to soap and water may be required in addition to informational campaigns.

Many governments around the world have recognised that households will require substantial support to be able to comply with the measures that are being asked of them. This can be seen, for example, in the unprecedented scale of the UK government’s support to households. Ensuring that governments in LICs are able to finance and run the large-scale programs of support that households are likely to require will be crucial in ensuring people are able to comply with the health measures and, ultimately, for stemming the global spread of COVID-19.

Data

All data presented are from low and lower-middle-income countries (which we collectively term LICs) as defined by the World Bank. Graphs plotted using the World Bank’s “World Country Polygons” series, which doesn’t include disputed territories.

Handwashing data come from country-level estimates produced by the JMP global database (https://washdata.org/) and are available for all low and lower-middle-income countries/territories other than Cape Verde, Djibouti, Eritrea, Kiribati, Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, Morocco, Nicaragua, Papua New Guinea, South Sudan, Ukraine, Uzbekistan, West Bank and Gaza.

Data on people per sleeping room, mobile telephone and television ownership and refrigerator ownership come from country-level estimates produced by stat-compiler using Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) data (https://www.statcompiler.com/en/#).

Data on household structure from household rosters (national representative) are obtained from Demographic and Health Survey program (https://dhsprogram.com/Data/). For each country, the latest round of data collection is used.

Data on household savings, ability to come up with emergency funds and access to bank accounts are from the Global Financial Inclusion Database (https://globalfindex.worldbank.org/).

UK data on household structure comes from 2017-18 Family Resources Survey.

[1] Handwashing facilities may be fixed or mobile and include a sink with tap water, buckets with taps, tippy-taps, and jugs or basins designated for handwashing. Soap includes bar soap, liquid soap, powder detergent, and soapy water but does not include ash, soil, sand or other handwashing agents.

[2]See Data section for data sources.

[3] The full criteria for being considered high risk is: have had an organ transplant; having certain types of cancer treatment; having blood or bone marrow cancer, such as leukaemia; having a severe lung condition, such as cystic fibrosis or severe asthma; having a condition that makes you much more likely to get infections; taking medicine that weakens your immune system; being pregnant; and having a serious heart condition. HIV-positive individuals without adequate treatment in lower-income countries (38% of the 38 million individuals living with HIV worldwide), particularly in Southern and Eastern Africa, are a source of uncertainty to guidance around social isolation. It is currently unknown to what extent this population group is at a higher risk if they contract Coronavirus (source: https://aidsinfo.unaids.org/#quicklinks-details).

[4]See Data section for data sources.

[5]https://www.nomisweb.co.uk/census/2011/qs413ew

[6]See Data section for data sources.

[7]See Data section for data sources.

[8]See Data section for data sources. UK figure estimated as: 0.75 x (% of HHs with infant under 1).

[9]See Data section for data sources.

[10]See Data section for data sources.