The government has published the provisional Local Government Finance Settlement for 2024–25, setting out funding allocations for councils next year. This largely confirmed intentions for the sector as a whole set out in a policy statement earlier this month, but we can now understand what these imply for specific councils.

Overall funding levels

The settlement confirmed a substantial cash-terms increase in councils’ core funding (or ‘core spending power’) next year: of £3.9 billion, or 6.5%. The most significant year-on-year changes in funding are:

- Increased revenues from council tax, with all councils again being allowed to increase bills by 3%, and those with social care responsibilities by a further 2%, without a local referendum. If all councils put bills up by the maximum allowed, revenues are expected to increase by around £2.1 billion next year.

- Increased business rate revenues, as a result of high inflation. Government has confirmed that retained rates revenues and the Revenue Support Grant will increase in line with CPI, which will add £1.2 billion to revenues next year.

- Additional social care grants worth £1.0 billion more than in 2023–24, following an increase of £2.5 billion that year. This was largely in line with what was announced last December, although an additional £365 million was provided in 2023–24 after the main settlement and an additional £205 million in 2024–25.

- A £406 million reduction in the Services Grant, while allocations of New Homes Bonus funding (£291 million), the Improved Better Care Fund (£2,140 million) and the Rural Services Delivery Grant (£95 million) have been frozen in cash terms.

- Finally, a funding guarantee that all councils will see at least a 3% cash rise in core spending power year-on-year, before they make any decisions over council tax rises. This guarantee is worth £197 million (compared with £133 million when it was first introduced last year).

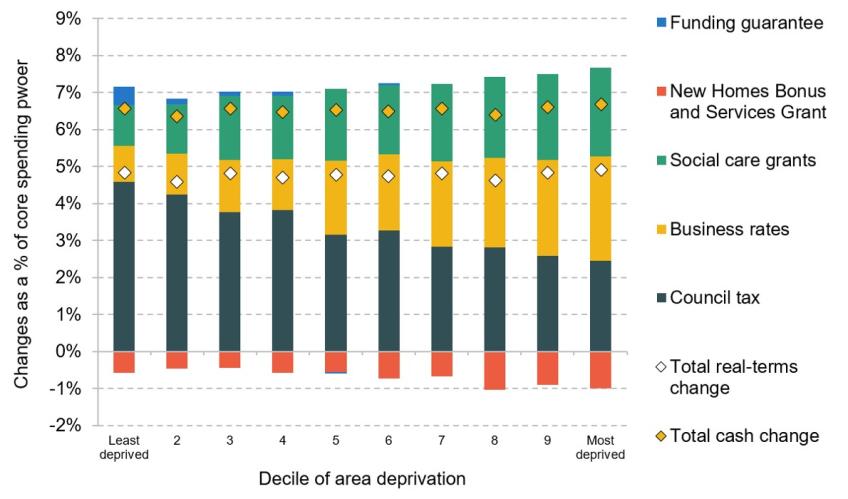

There has been no attempt to target bigger rises to more deprived areas

Over the last two years, councils in more deprived areas have seen slightly larger rises in core spending power. At the last settlement, the most deprived tenth of areas saw cash-terms increases of 9.9% on average, compared with 7.6% in the least deprived tenth. This pattern will not continue in 2024–25, with very similar rises in core spending power amongst the most and least deprived areas. Increases in council tax generate more revenue in more affluent areas, but this is offset by the fact that more deprived areas tend to have higher assessed spending needs, and so are allowed to retain more income through the business rates retention scheme and receive a greater share of additional social care grants.

Figure 1. Change in core spending power between 2023–24 and 2024–25 by decile of area deprivation, as a % of core spending power

Note: Bars show cash-terms change for each funding element as a % of core spending power in 2023–24. Yellow and white diamonds show cash-terms and real-terms overall change in core spending power. ‘Social care grants’ includes rolled-in MSIF workforce fund in 2023–24. Deprivation deciles are based on IMD 2019 Average Score at the upper-tier authority level.

Source: Provisional Local Government Finance Settlement, 2024-25; English Indices of Deprivation, 2019.

The continued focus on funding for social care, through higher council tax rises and additional ringfenced grants, will see rises of 6.6% on average for councils with responsibility for social care. Shire district councils will see their spending power rise by 4.9% on average (and, like in the current year, will benefit most from the funding guarantee).

How has funding changed over time?

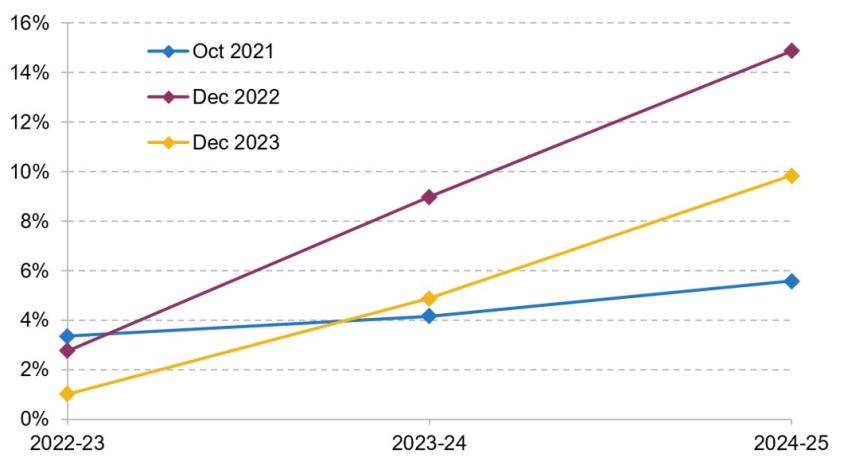

First, how does this compare with the plans that the government set out at the 2021 Spending Review? At that point, grant funding for councils’ existing responsibilities was set to increase in 2022–23, but to then be frozen in cash terms, implying relatively small real-terms increases in overall spending power in subsequent years. As shown by the blue line in Figure 2, we expected like-for-like core spending power next year to be 5.6% higher in real terms than in 2021–22.

Last December, the government changed course, announcing additional social care grants and confirming councils would retain the funding for major reforms to the social care system that they no longer needed to pay for. Along with faster council tax rises and the indexation of business rates revenues with CPI, like-for-like core spending power was expected to be fully 15% higher in real terms next year than in 2021–22 (as shown in purple in Figure 2).

Since then, economy-wide inflation has been much higher than was expected even last December, and has almost entirely offset the extra funding provided this financial year. We estimate core spending power in 2023–24 will have been just under 5% higher in real terms than in 2021–22, compared with the 9% expected at last year’s settlement.

Next year, we now expect core spending power to increase by 4.7% in real terms, and to be around 10% higher in real terms than in 2021–22. This is more than was provided for at the spending review, but will be around 4% lower in real terms than councils might have expected based on last year’s policy statement.

Figure 2. Real-terms local government core spending power compared with 2021–22, under different plans

Note: Real-terms figures reflect the most recent GDP deflator forecasts when plans were announced.

Source: Autumn Budget and Spending Review 2021; Provisional Local Government Finance Settlement, 2023–24; Provisional Local Government Finance Settlement, 2024–25; OBR Economic and Fiscal Outlook – October 2021, November 2022 and November 2023.

Looking over a longer period (and accounting for population growth as well as inflation), spending power in real terms per capita will have matched the level in 2015–16 this financial year, and will surpass that level by around 4.0% next year.

Councils’ cost pressures are outpacing economy-wide inflation

It may therefore seem surprising that so many councils are reporting financial struggles, especially given just a few years ago they were having to manage after years of real-terms cuts to their funding.

This conundrum is explained by the fact that the costs facing councils appear to be growing significantly faster than whole-economy inflation. Part of this is a timing effect: inflation can affect councils with a lag, as contracts with suppliers (e.g. for social care or cleaning services) are often updated each year based on inflation at some point in the prior year. For 2023–24, that may mean Autumn 2022, when inflation reached its peak: over 11% for CPI inflation, which is far higher than forecast inflation for 2023–24 itself.

However, it is more than just a timing effect: some important costs facing councils are going up by more than general inflation. The National Living Wage increased by 9.7% in April 2023 and is set to increase by 9.8% in April 2024, which may put upwards pressure on wages more generally among lower-paid workers. The LGA has highlighted the cost of children’s social care (especially specialist placements), homelessness services (particularly temporary accommodation) and home-to-school transport (most notably for pupils with special educational needs) as rising particularly rapidly. Indeed, recently published spending data for the period April to September 2023 show spending on children’s social care services up 16% and on homelessness and related services up 26% compared with the same period in 2022, both outpacing budgeted spend. This means councils look set to draw down their reserves by even more than the £1.9 billion they budgeted for this year (although it is worth remembering that they paid billions into reserves during the COVID-19 pandemic).

The real pain looks set to be from 2025–26 onwards

2023–24 and 2024–25 are therefore tougher years financially for councils than economy-wide inflation figures would suggest.

But we would hazard that the worst could be yet to come. In particular, if one takes seriously the overall spending totals pencilled in by the Chancellor, the next spending review period could be a much tougher one for local government than the current period. In particular, day-to-day funding for public services (what is termed the resource departmental expenditure limit or RDEL) is due to increase by just 1% above economy-wide inflation in each of the years between 2025–26 and 2028–29. IFS colleagues have estimated that, based on reasonable assumptions about what may be needed for the NHS and schools and existing commitments on defence, overseas aid and childcare, funding for other services in England may need to be cut by an average of over 3% per year in real terms. That means that even cash-flat settlements for the grant-funding components of councils’ core spending power, which would equate to a cut in grant funding of around 1.7% in real terms per year, would put councils in a better position than most other ‘unprotected’ services.

The difficulty of making big cuts to the same ‘unprotected’ services that bore the brunt of the 2010s’ austerity means that it is likely spending plans will be topped up somewhat – the figures laid out by the Chancellor should probably not be taken as central forecasts of actual spending. But with a high debt burden, high interest costs, and a tax burden already heading to record levels, it seems unlikely that such top-ups will be enough to avoid some very difficult decisions at the next spending review.

If grant funding is constrained and with business rates increases capped at inflation, councils will therefore again find themselves reliant on council tax for overall increases in funding. But with both inflation and wage growth forecast to fall closer to 2% in the coming years, increases on the scale of recent years – typically 4.99% – may be harder to justify to the electorate. And it is much harder to compensate for differences in the amount different councils can raise from council tax when grant funding is frozen or being cut and business rate revenues are growing slowly: it requires even bigger cuts to grants for councils in affluent areas to redistribute revenues to councils in poorer areas.

In such a financially constrained future, it will be even more important that the funding system channels funding to where it is most needed – which it currently fails to do. The government claims it remains committed to improving the finance system in the next parliament, but that now is a time for stability rather than fundamental reform. At some stage, an understandable desire for stability becomes damaging inertia. Redistributing funding in line with up-to-date assessments of councils’ needs will be even more difficult politically in the next parliament when the overall funding pot is fixed or even shrinking, but at some point it must be done.

These interrelated challenges – the limited size of the funding pie, and the increasing challenge of slicing it up across the country fairly – mean that it is from 2025 onwards that councils and DLUHC are likely to face the stormiest waters.