This blog post was originally published on VoxDev.

Increasing property taxes can boost revenues for developing countries, but enforcement may threaten the welfare of liquidity-constrained households

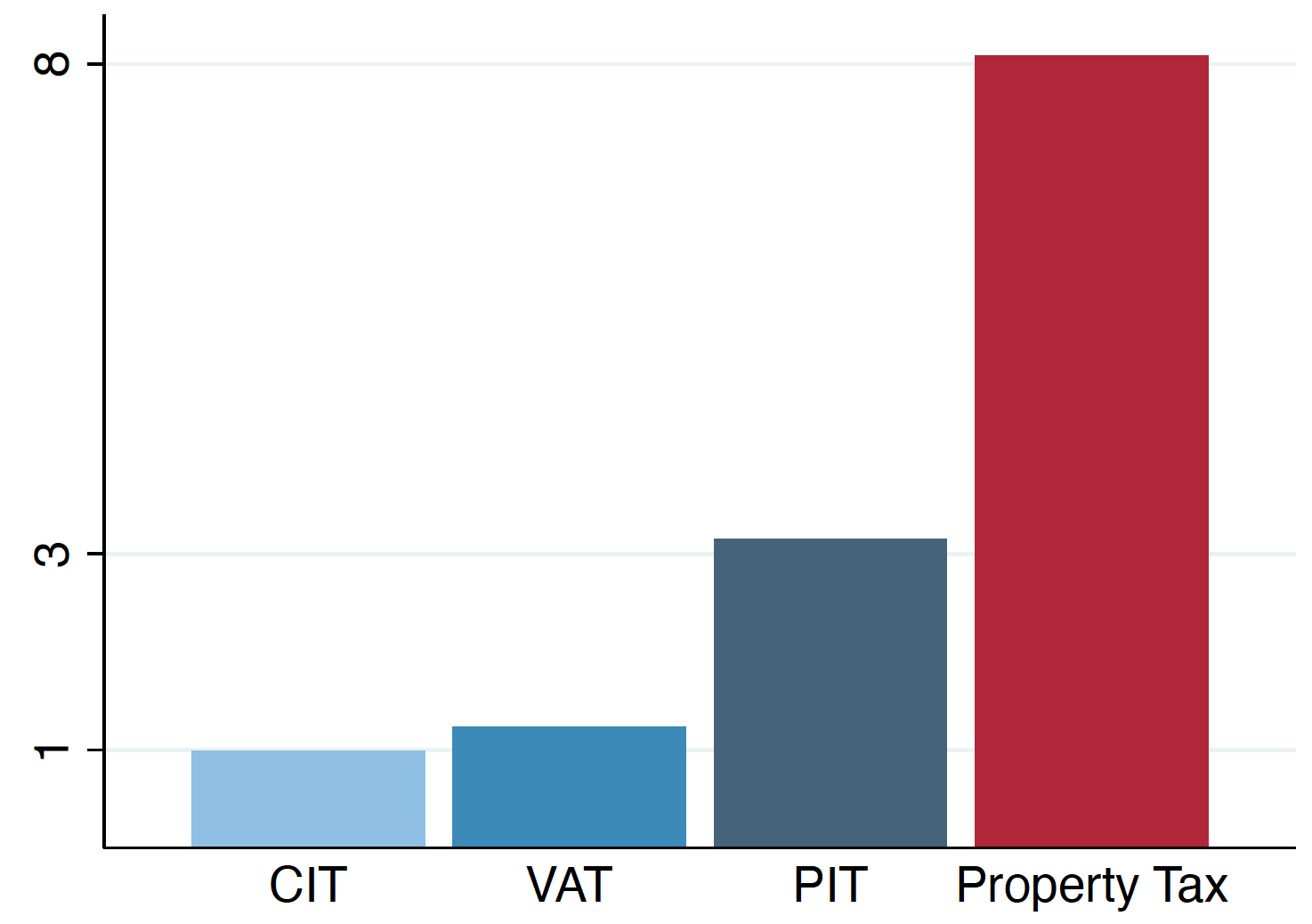

Developing countries raise less revenue as a share of GDP than higher-income countries in general, but the gap is striking for property taxes in particular (see Figure 1). The low reliance on property taxes for revenue is rather puzzling as the easy observability of property makes this form of taxation harder to evade than other types of taxes, and revenues collected from property taxes support key expenditure priorities like redistribution and public goods spending. Why, then, do developing countries not leverage property taxes more as a revenue source?

Figure 1 Ratio of tax revenue to GDP in high- vs low-income countries

Note: The figure shows the ration of tax revenue (as a share of GDP) in high vs low-income countries, for different taxes. For example, high and low-income countries raise about the same share of their GDP as corporate income tax (CIT) revenue. VAT stands for value-added tax, PIT for personal income tax.

Previous work has linked effectiveness in tax revenue collection to administrative capacity. In general, when enforcement capacity is limited, the optimal mix of tax instruments may differ from the mix prescribed by traditional public finance theory (Best et al. 2015). Further, governments focused on maximising welfare rather than revenue alone must think about the greater precarity of consumption among residents of developing countries, which can be adversely affected by taxation.

In a new study (Brockmeyer, Estefan, Ramirez Arras, and Serrato 2020) , we examine the impacts of a property tax reform in Mexico City implemented from 2008 to 2012. We assess whether the reform succeeded in increasing revenues, and attempt to disentangle the behavioural responses to both the tax rate increases as well as a contemporaneous enforcement initiative. We emphasise that even when states can increase revenue, doing so may impose welfare costs on taxpayers that offset potential gains from increased government spending.

Property tax reforms in Mexico City

In our paper, we marry Duflo’s (2017) economists-as-plumbers approach – emphasising how tinkering with policy details can significantly affect outcomes – with Slemrod and Gillitzer’s (2013) tax systems framework that highlights the interplay of tax rates, remittance rules, and enforcement in optimal tax design.

Our work uses administrative tax data on all residential properties in the second-largest city in the Western Hemisphere, Mexico City, which exhibits two features typical of developing contexts: households with liquidity constraints and a government with limited enforcement capacity. In Mexico City, less than 20% of households have access to credit cards and over 40% of taxpayers are delinquent on their property taxes.

To identify the effects of property tax rate changes, we leverage the gradual repeal of abatements on gross property tax liabilities, starting in 2008 and proceeding year by year across cadastral tax bands. The tax cuts were initially aimed to smooth the increase in mean tax liability across tax bands, but after the 2008 financial crisis, the city government started repealing the cuts on individual bands, effectively increasing the property tax rate on households within these bands, in some cases, by a great deal.

We model the government's trade-off between raising revenue to provide public goods and containing the welfare costs of raising tax rates. Our model evaluates the welfare effects of enforcement by comparing the revenue gains from enforcement to the private costs incurred by taxpayers facing enforcement actions. We then conduct an empirical analysis of the actual reform and plug in the values to simulate the effects of different policies.

Tax reforms increase revenue, but decrease compliance

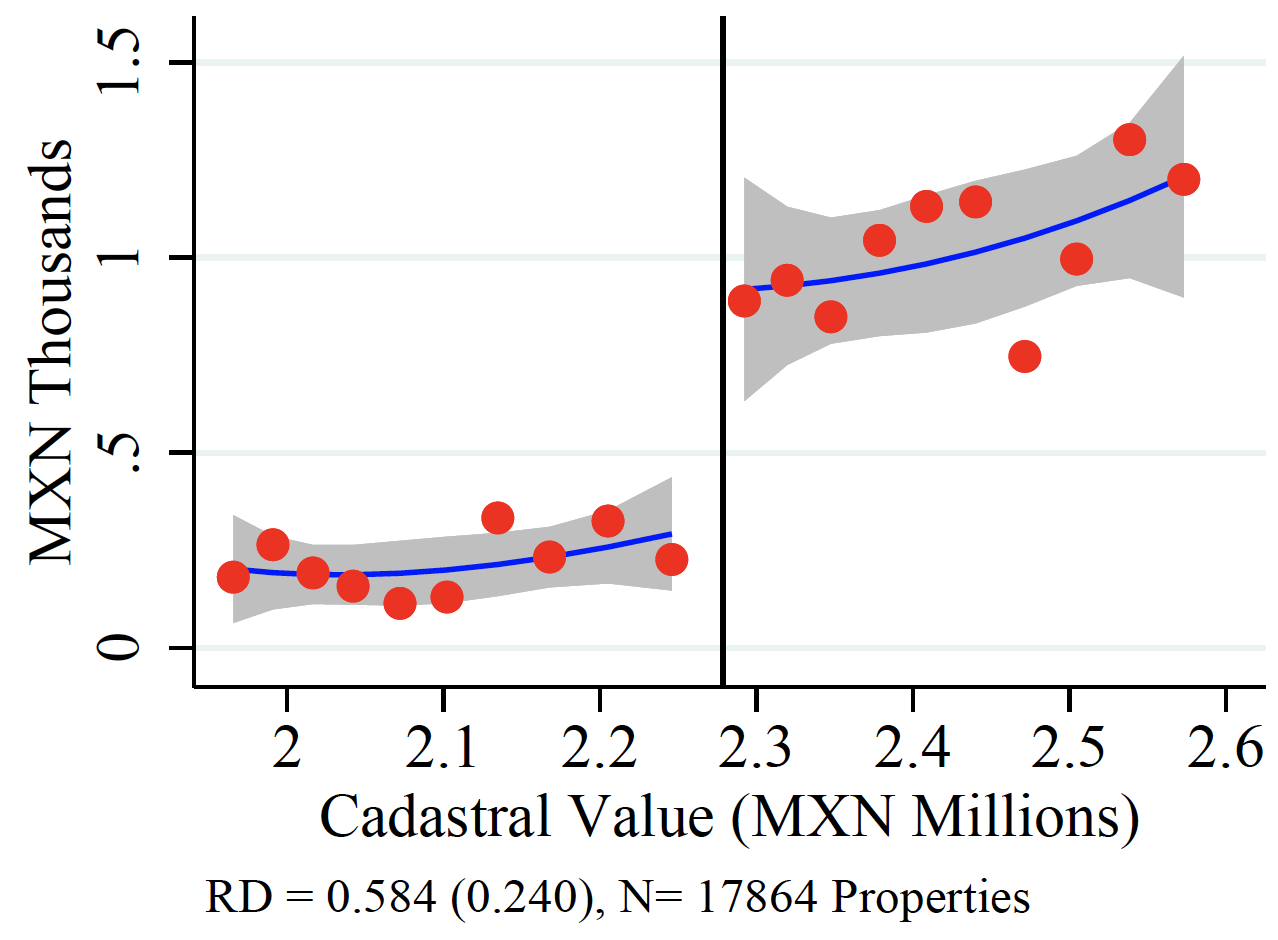

Our empirical assessment of the reform uses a regression discontinuity design to calculate the short-term effects of the abatement repeal for three bands (bands I, H, and G) over three years (2010, 2011, and 2012), which imposed considerable increases in the mean tax rate (9.1, 12.1, and 18.0 basis points, representing jumps of 20%, 27%, and 47%, respectively). We identify how the rate increases changed the payment and compliance behaviour of the affected taxpayers by comparing it to that of unaffected taxpayers on the other side of the band thresholds, who are otherwise statistically indistinguishable from the treated group. As shown in Figure 2, we find that tax payments did indeed rise, albeit less than mechanically expected because compliance fell by some 3.2 to 6.2 percentage points.

Figure 2 Response to tax rate increase: Regression discontinuity evidence

A) Tax payment amount

B) Compliance share

Note: Figures based on the 2009-2010 treatment. The red dots represent the mean outcome in equally spaced cadastral value bins. The solid blue lines (grey areas) depict a fitted third-order polynomial (the corresponding 95 percent confidence intervals). The vertical black lines mark the thresholds between the control and treatment bands. Properties to the right of the threshold are treated with a tax rate increase.

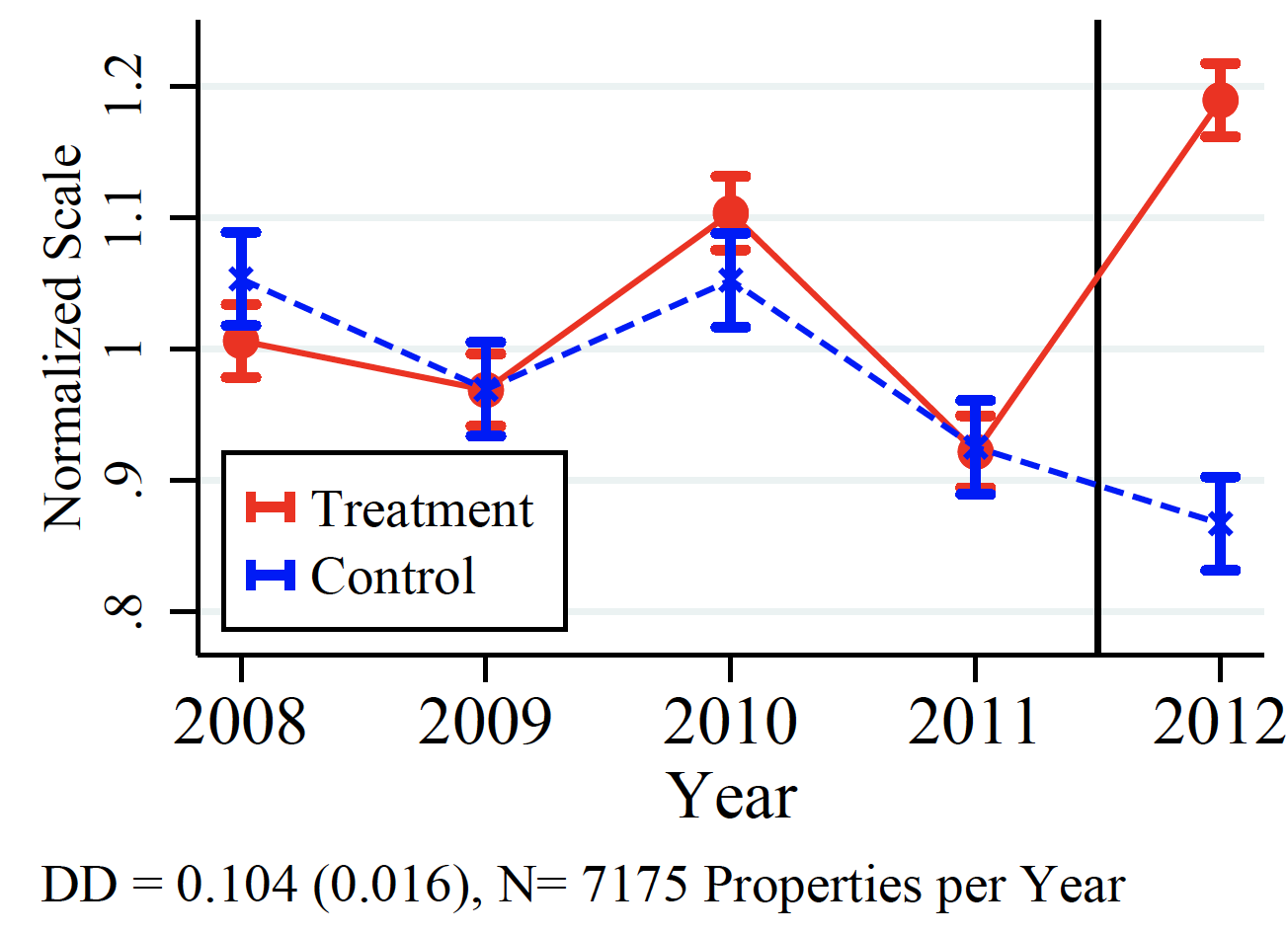

To assess the medium-term effects, we use a difference-in-differences (DiD) approach to compare treated properties to those in high value bands but with no change in their mean tax rate. By observing taxpayers over windows of up to three years after the initial 2010 reform, we find that the medium-term effects largely mirror the short-term ones. In short, the behavioural effects of the reforms persisted for at least several years, and the tax increases did boost revenue across the board.

Does increasing enforcement boost compliance?

In view of this drop-off in compliance and the general prevalence of payment delinquency in Mexico City, we investigate whether the government can increase compliance by stepping up enforcement. We use a field experiment designed and evaluated together with Mexico City’s Ministry of Finance in which the ministry sent 80,000 taxpayers variations of a letter requesting payment on their delinquent taxes within 15 days. Half the letters emphasised the penalties property owners could face for failure to pay their taxes (the sanctions treatment), while the other half underscored the community services that property tax revenue helps fund (the public goods treatment). Ten thousand delinquent taxpayers served as the control group and received no letters.

The outcomes of this intervention were clear: compared to taxpayers in the control group, recipients of the sanctions letter were three times as likely to make a payment, and paid twice as much. Property owners who received the public goods letter reacted similarly, but less markedly. These effects underscore that even low-capacity governments have cost-effective means of boosting tax compliance through enforcement. Whether they should do so when households are liquidity constrained is another question.

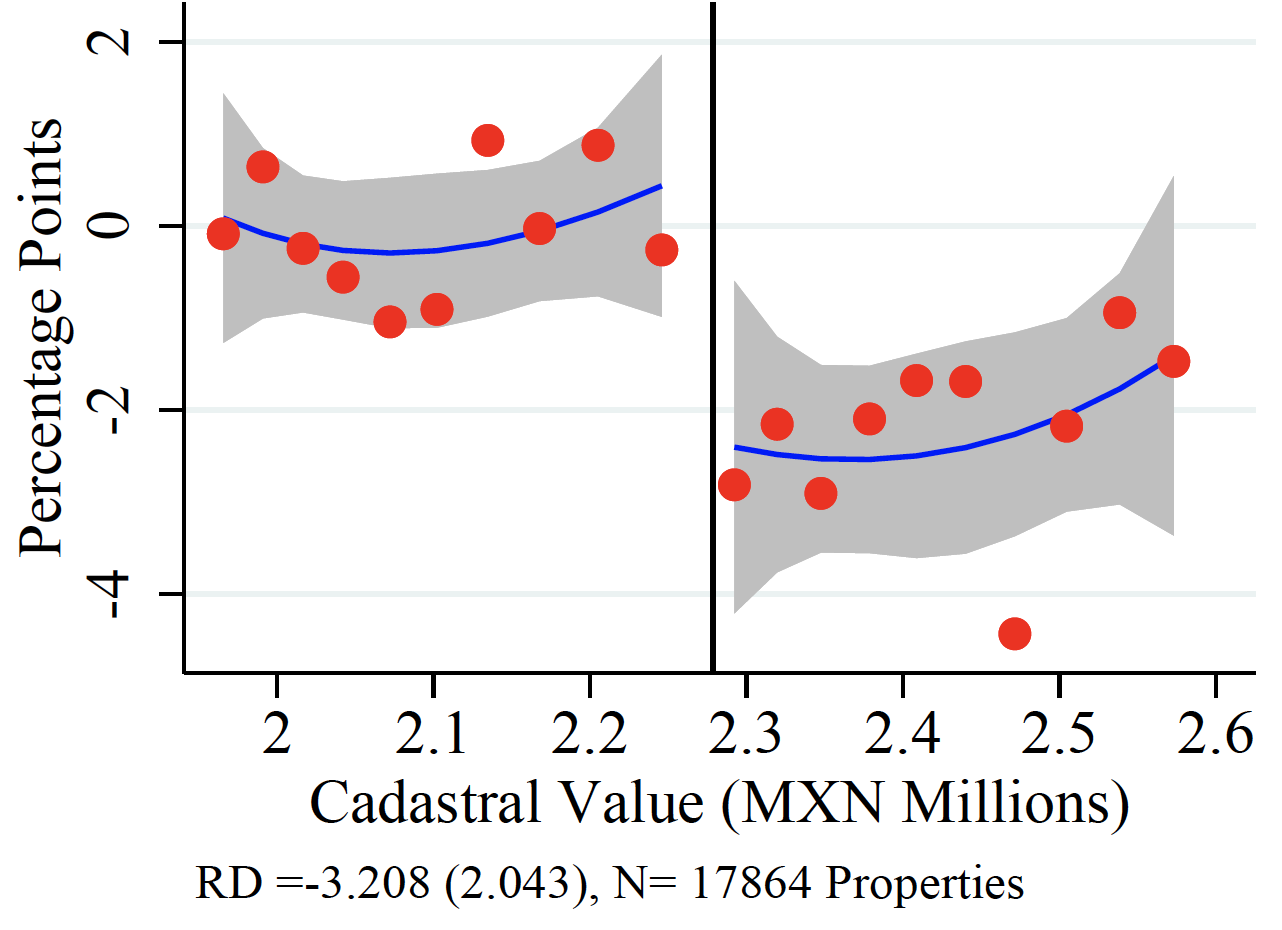

Liquidity constraints and taxpayer welfare

Our model reveals that because the property tax is levied on an illiquid asset, the presence of household liquidity constraints reduces the optimal tax rate because such constraints increase the welfare cost of taxation by cutting into household consumption. We empirically identify that liquidity constraints were indeed activated in the affected households after the tax rate reforms based on their take-up of payment in instalments, compared to one-time payments. We also review consumption data and find that for liquidity-constrained households, the reforms interfered with the treated households’ consumption patterns. We conclude that property tax hikes can impose hardships on taxpayers in the absence of policies that provide households with liquidity.

Figure 3 Likelihood of paying in instalments after tax rate increase

Note: Figure based on the 2012 reform. The sample is restricted to taxpayers that register a payment (including partial payments). The outcome is a dummy indicating whether the taxpayer paid in instalments as opposed to paying all at once.

Optimising tax policy for revenue and welfare

We conclude our analysis by plugging the revenue elasticities from taxation and enforcement calculated from the empirical data into our model. We find that governments could substantially increase property tax rates to boost revenue, with corresponding welfare gains from public spending, but stepping up enforcement may harm welfare. Put differently, a welfare-maximising government should increase tax rates but not enforcement.

Finally, we note that offering taxpayers liquidity could help smooth the functioning of property tax systems in developing states while allowing governments to raise tax rates further. Indeed, because Mexico City is similar to other developing contexts in terms of household liquidity constraints and tax capacity, our findings carry broad relevance for policymakers and further research.

References

Best, M, A Brockmeyer, H Kleven, J Spinnewijn, and M Waseem (2015), “Production vs Revenue Efficiency with Low Tax Compliance: Theory and Evidence from Pakistan”, Journal of Political Economy 123(6): 1311–1355.

Brockmeyer, A, A Estefan, K Ramírez Arras, J C Suárez Serrato (2020), “Taxing Property in Developing Countries: Theory and Evidence from Mexico”, working paper.

Duflo, E (2017), “Richard T. Ely Lecture: The Economist as Plumber”, American Economic Review 107(5): 1–26.

Keen, M and J Slemrod (2017), “Optimal Tax Administration”, Journal of Public Economics 152: 133-142.

Pomeranz, D and J Vila-Belda (2019), “Taking State-Capacity Research to the Field: Insights from Collaborations with Tax Authorities”, Annual Review of Economics 11(1): 755–781.

Slemrod, S and C Gillitzer (2013), “Tax Systems”, MIT Press, Zeuthen Lecture Series, 2013.

Weigel, J (2020), “The Participation Dividend of Taxation: How Citizens in Congo Engage More with the State When it Tries to Tax Them”, Quarterly Journal of Economics 135(4): 1849–1903.