Key findings

1. Global growth has so far remained relatively resilient through an extreme surge in inflation paired with one of the sharpest monetary tightening cycles in generations. This suggests that both contracting supply and expanding demand contributed to rising prices and raises a key question for the coming 12 months: have central banks really managed a soft landing of the global economy in such a complex situation? Or is the world facing a hard landing because central banks overreacted to mostly supply-driven inflation, or because they still underestimate the shift in inflation dynamics and will have to go even further to break them?

2. A soft landing is possible. Global inflation has fallen from more than 9% in 2022 to below 6%. Energy disinflation may have run its course, and food inflation is falling. Remaining pandemic-era supply disruptions have faded, suggesting consumer goods will get cheaper. Once wages have adjusted to higher prices, services inflation should also fall. In Europe – but not in the US – we expect inflation to fall below 2% in the second half of 2024.

3. Lower inflation, higher growth? Supply-driven inflation lowers growth, so as it reverses it should stabilise demand while at the same time allowing central banks to cut interest rates. This makes a soft landing more likely, particularly in some emerging markets in Asia and South America, where growth prospects have brightened and central banks are already cutting rates. But the path to a soft landing looks increasingly narrow – especially in the US and Europe.

4. Has the US battle against inflation only just begun? In the US, inflation is expected to stay above 2% beyond 2024. Wage growth is not normalising, and growth and the housing market are picking up despite high interest rates. The risk that the Fed has not yet done enough is significant. While the bar to significant further rate hikes is high, rates may have to stay high for longer to achieve the necessary cooling of growth and inflation.

5. Even in weak-growth Europe, inflation may not return to target quickly. Wage growth is set to remain high and services inflation usually moves in lockstep in both the Euro Area and the US. Wage growth would have to be absorbed by falling profit margins or by rising productivity growth. However, neither has been the norm in recent decades.

6. Despite strong wage growth and fading inflation, we expect the Euro Area economy to shrink for the next three quarters. Weak external demand, labour shortages, uncompetitive energy prices and the housing market are expected to weigh on growth before the full extent of the policy tightening has taken effect. In contrast to the US, there is a significant risk that the European Central Bank has already overtightened. If the Euro Area falls into a protracted recession, and deflationary tendencies return, the ECB would need to react quickly and decisively to avoid returning to the effective lower bound.

7. Global recession? Excluding China, we are now forecasting world GDP growth of less than 1% in 2024, fulfilling some definitions of a global recession. And for China we are not optimistic either. China’s economy is struggling to gain momentum as the global manufacturing cycle weighs and structural weaknesses such as demographics and high debt combine with hesitant stimulus.

8. Global interest rates are most likely to fall. Rate hike cycles are coming to an end at 4% in the Euro Area, just over 5% in the UK and just under 6% in the US. Weak growth makes rate cuts most likely from Q2 2024, especially in Europe. In the US, the risks are skewed towards higher rates for longer, however.

1.1 Introduction

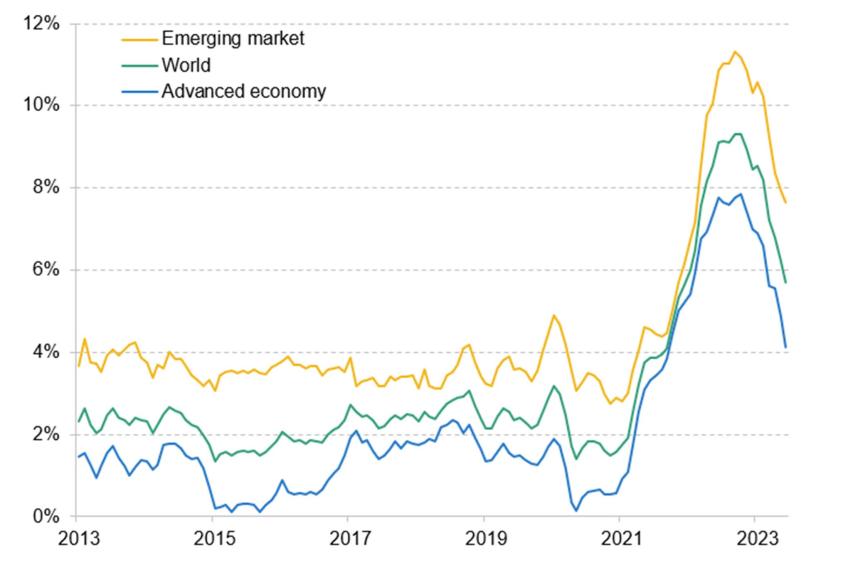

Even though global inflation rates have come down significantly since 2022, the fight against inflation continues to dominate the global economic policy agenda. At the time of the 2022 Green Budget, in October 2022, world inflation peaked at 9.3% year-on-year, more than three times higher than the pre-pandemic norm of around 3% (see Figure 1.1). By June 2023, it had fallen halfway back to the norm, and stood at just under 6%. Both the rise and decline were fairly uniform across advanced economies and emerging markets. In the former, inflation peaked in October 2022 at 8% and fell to just over 4% in June, 2 percentage points (ppt) above ‘normal’. In emerging economies, inflation peaked at 11.3% in September 2022 and was by June back down to just under 8%, 4ppt above the norm of 4%. Even outliers such as Turkey have seen year-on-year inflation halve, from 80% to 40% over the same period.

Figure 1.1. World composite inflation (year-on-year %)

Source: Haver Analytics and Citi Research.

As we highlighted in chapter 1 of last year’s Green Budget, the major drivers of the inflation surge – and subsequent reversal – were widespread supply-side factors, such as pandemic-era supply chain disruptions, labour force distortions, and more recently the repercussions of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine for energy and food prices. This explains the strong global co-movement of inflation rates. Less clear is the role of demand. During the pandemic, many governments generously maintained or even increased corporate and household incomes, for example by sending out checks (US) or allowing employers to put employees on furlough (Europe), funded by aggressive government borrowing. This was facilitated by unprecedented central bank easing, especially asset purchases, and did not just allow households in some parts of the world to maintain large parts of spending (Europe) or even increase it (US) during the pandemic, but also to save large amounts and maintain spending beyond the end of the pandemic.

The high inflation rates caused by this combination of a series of large negative supply shocks and positive demand shocks risked becoming so persistent that they would dislodge inflation expectations and thus perpetuate high inflation. Central banks therefore stepped in to anchor expectations, break the inflation surge and swiftly return inflation to target. With inflation rates now well into their decline in most parts of the world, we and most forecasters see global central bank interest rates close to the peak or even starting to reverse.

Global growth has remained resilient through the extreme surge in inflation paired with one of the sharpest monetary tightening cycles in generations, which suggests that both supply and demand contributed to rising prices. That raises the key question for the coming 12 months: have central banks really managed a soft landing of the global economy in such a complex situation? Or is the world facing a hard landing because central banks overreacted to mostly supply-driven inflation, and exaggerated concerns that monetary policymakers could lose credibility and inflation expectations could rise? Or do central banks still underestimate the shift in inflation dynamics, and will they therefore have to tighten even further to break them?

We begin in Section 1.2 by discussing how the easing of supply constraints, and the resilience of demand, point to a possible ‘soft landing’. We then consider, in Section 1.3, the trends in the labour market and elsewhere which point to the risk of inflation (and interest rates) staying higher for longer. In Section 1.4, we consider the possibility that central banks have already gone too far. In Section 1.5, we examine how the outlook varies across regions, before finally presenting Citi’s latest forecasts (Section 1.6) and concluding (Section 1.7).

1.2 Can we manage a soft landing?

Over the past three years, the world experienced a series of highly unusual supply disruptions and thus cost shocks.

Pandemic-induced supply shocks

First were the shocks triggered by the public health policy reaction to the pandemic, which largely affected goods inflation and have largely faded by now:

- The global shipping market has relaxed, with key freight cost indices well down on post-pandemic peaks and in some cases below pre-pandemic levels. The Baltic Dry Index, which measures daily rates of dry bulk carrier ships, is averaging 1142 so far this year, down 75% from the 2022 peak and actually 15% below the 2018–19 average. The Harper Petersen Index, which measures weekly container vessel spot chart rates, has averaged 1156 so far this year, which is still double the pre-pandemic average, but also down 75% from the 2022 peak, despite issues around the Panama Canal, for example

- Supplier lead times are shortening substantially. In the US Institute for Supply Management (ISM) manufacturing index, for example, supplier lead times were lengthening at their strongest pace since the 1970s in 2021, but are now shortening at the fastest rate since the global financial crisis in 2009.

- Where inventories of finished goods were depleted in 2021, now firms are reporting that they have too much in stock. In Germany’s widely followed ifo manufacturing survey, for example, firms are now reporting inventories nearly as full relative to demand as they were during the first lockdown in 2020.

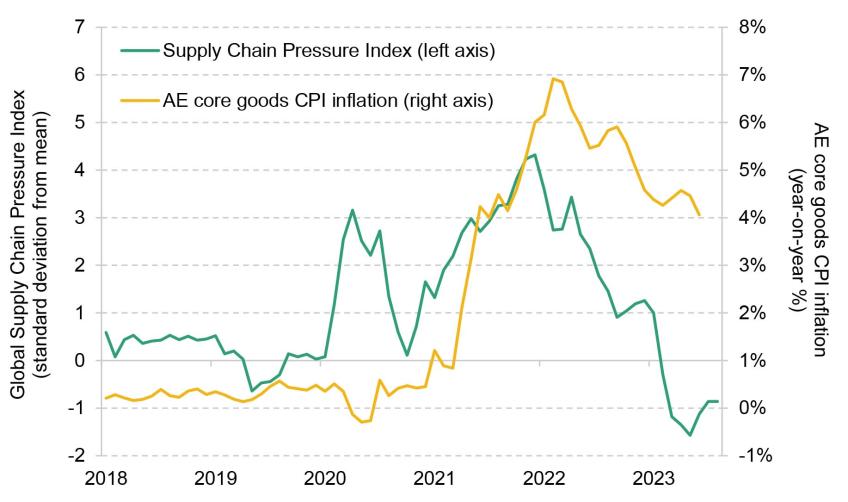

In summary, the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Global Supply Chain Pressure Index has dropped from more than four standard deviations above its post-1997 average in late 2021 to a trough of one-and-a-half standard deviations below it this year (Figure 1.2). This has triggered a disinflation process in core goods, though one which is far from complete (also shown in Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.2. Global supply chain pressures (standard deviation from mean) and advanced economy core goods CPI inflation (year-on-year %)

Note: AE = advanced economy and represents a weighted average of US, Euro Area, Japan and UK non-energy industrial goods inflation.

Source: New York Fed, Haver Analytics and Citi Research.

Energy shocks

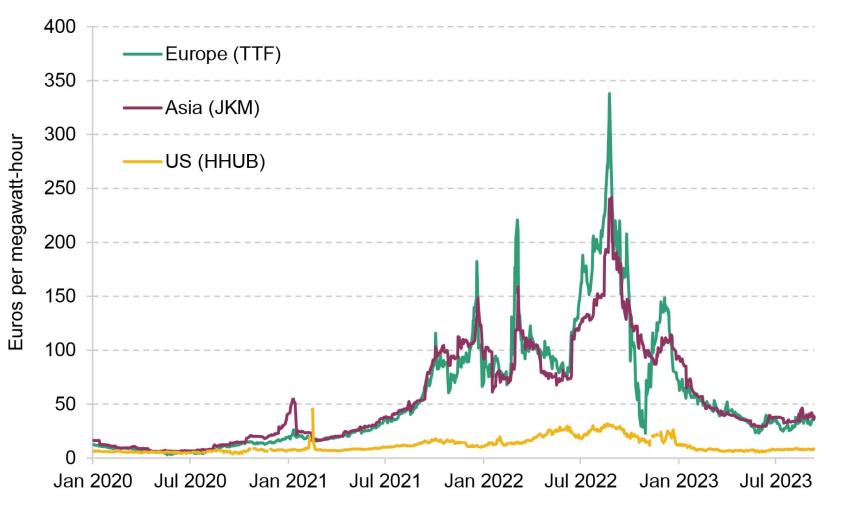

Secondly – and quantitatively even more importantly – large parts of the world experienced energy shocks, aggravated by Russia’s war in Ukraine. At the time of writing the 2022 IFS Green Budget, natural gas prices in Europe and Asia had risen up to twenty-fold compared with pre-pandemic levels (see Figure 1.3). One year on, they are still roughly double their pre-pandemic levels, but that is 90% lower than last year.

Figure 1.3. Wholesale spot natural gas prices (€/MWh): Europe, Asia and US

Note: TTF = Title Transfer Facility; JKM = Japan Korea Marker; HHUB = Henry Hub.

Source: BEA and Citi Research.

Unlike semiconductor production or global shipping capacity, energy supply has not been repaired, however. Most of the fall in prices is the result of adjustments in demand, which indicates a longer-lasting impact on the economy. The big gas pipelines from Russia to the EU remain mostly blocked, while global liquefied natural gas (LNG) supply is broadly unchanged since last year and is expected to remain so for several more years. Instead, gas consumption has fallen by 22% in the EU between January–May 2021 and January–May 2023, partly because of mild weather and partly because households, the state and businesses responded to high prices by cutting demand. So far, there is no sign of demand picking up again despite lower prices, suggesting that demand destruction is permanent for better (energy saving) or worse (production relocations).

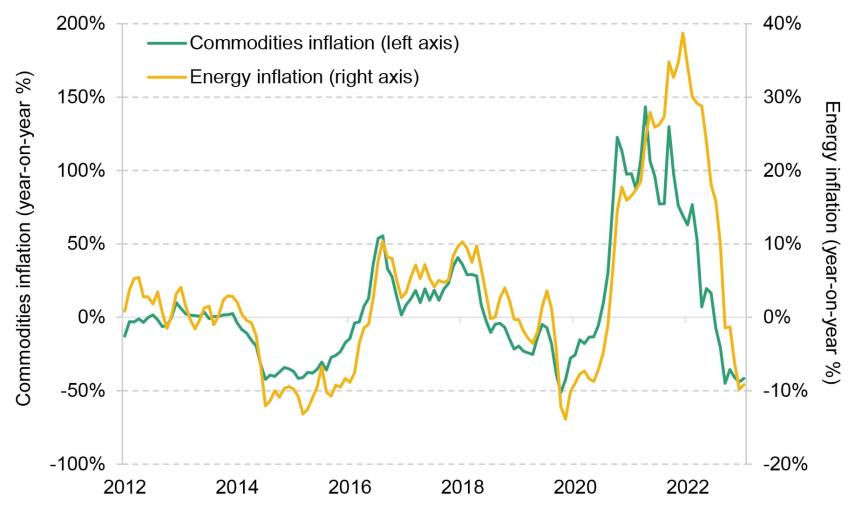

The adjustments in wholesale energy markets are feeding through to consumers, albeit cushioned by long-term fixed-price contracts and government price caps. In the Euro Area, energy consumer price inflation, which also includes electricity and car fuels, peaked in October 2022 at 41.3% year-on-year. In the UK, it peaked at 59.3% in the same month. Since then, energy consumer price inflation in both the Euro Area and the UK is following the downwards trend already seen in Japan and the US (where year-on-year energy CPI inflation already peaked at 20.8% and 41.6% in March and June 2022, respectively). Across advanced economies, energy inflation is now in deeply negative territory (see Figure 1.4), but is unlikely to fall further.

Figure 1.4. Commodities and energy inflation (year-on-year %): advanced economies

Note: Energy inflation = weighted average of US, Euro Area, Japan and UK energy CPI inflation rates. Commodities inflation in USD, including energy commodities.

Source: HWWI, Eurostat, BLS, ONS, MIC and Citi Research.

In fact, energy prices will likely rise by more than the rest of the consumer basket over the coming years. Investment into new sources of energy to replace Russian energy and fulfil green transition targets will be paid for, at least in part, by users. In the EU alone, estimates suggest a need for around €600 billion (4% of GDP) of annual investment for the green transition (European Commission, 2023). Governments are likely to use price incentives to discourage the use of emission-heavy fossil fuels via CO2 prices or emissions trading certificates. That will further add to the energy prices consumers face and may force central banks to run higher inflation rates in order to bring price growth excluding energy to below 2% in order to hit their inflation targets.

As an aside, whereas global trade ensures that inflation in energy commodities has been fairly similar across different regions (with the exception of US natural gas prices), the impact of energy policies on inflation will likely differ substantially across countries and regions. Energy prices have risen by only 7% since 2019 in Japan, by just over 30% in the US, but by nearly 40% in the Euro Area and nearly 50% in the UK. This partly reflects the differing political will to reduce the consumption of energy via price tools.

Food prices

Third, war has also led to an increase in global food prices. Ukraine is a major food exporter, but more importantly, energy prices more generally – and gas prices especially – tend to fuel food inflation via the rising cost of fertiliser production, for example. Food inflation peaked in the US at 13.5% shortly after energy inflation peaked. In the Euro Area and in the UK, food inflation peaked at just under 20% in March 2023, five months later than energy inflation, while in Japan food inflation fell for the first time this year in June, more than a year after the energy inflation peak.

As with energy, we expect food inflation to be volatile and relatively high on average over the coming years. Climate change, but also specifically Russia’s terminating the agreement over Ukrainian grain exports via the Black Sea or the impact of El Niño, could lead to new spikes. Despite that, prospects are for lower food price inflation in 2024, which matters greatly for households given that food and beverages account for between 10% (US) and 20% (Euro Area, Japan) of the consumer price basket (and more for lower-income households). It is worth highlighting that food is a much larger part of the consumer basket in many emerging economies, e.g. 38% in Russia and 46% in India (but not everywhere, with Brazil and South Africa on par with the Euro Area at 19%, for example). Of course, food staples differ from region to region, and so food inflation trends can diverge quite a bit. However, in developing and emerging economies, food prices are often also politically very sensitive. Volatile food prices can thus trigger political as well as economic instability.

The demand side

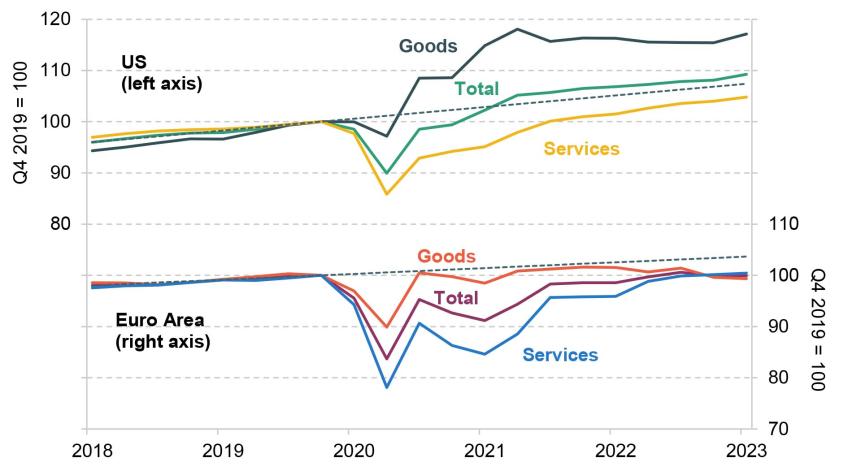

Fourth, the demand side has also experienced one-off shocks which are bound to fade quasi-automatically. During the pandemic, public health restrictions meant that households and companies were forced to buy goods instead of services. Especially where stimulus was strongly skewed towards supporting consumption rather than production, this spike in demand for goods occurred just as supply plunged, causing a large rise in inflation. With a delay, the surge in US demand also affected the rest of the world, amplified by the strong dollar.

Households do not buy durable goods such as televisions and fitness gear every year, however. With the end of lockdowns and travel disruptions, consumer demand is now rotating back to services (see Figure 1.5). In addition, rising interest rates tend to weigh on investment via tightening financing conditions, and therefore on demand for capital goods and consumer durables. Since services are far less traded than goods, this reduction in demand for goods has led to a global trade recession, which is weighing on tradeable sectors such as manufacturing, and the global manufacturing hubs such as China and Germany, relative to more services-exposed economies such as the US or France. These factors have added to the drag on core goods inflation, compounding the effects of easing supply constraints (see Figure 1.2 above).

Figure 1.5. Real-terms private consumption of goods and services: US and Euro Area

Note: Dotted lines denote pre-pandemic trends for total consumption.

Source: BEA and Citi Research.

Even services inflation may eventually come down more-or-less automatically, for three reasons. First, while services consumption cannot be shifted in time as easily as goods consumption (e.g. holiday season is every year), there are reasons to believe that tourism and concert visits are currently above their long-term trends after the pandemic and will eventually settle at lower levels. Airfares inflation may not stay as high as at the moment.

Second, energy and food are inputs in the services sector as well. Some services such as restaurants are directly exposed to rising food prices, for example, and others to energy prices, such as transport services, airfares or package holidays. In addition, service prices are more closely related to wage growth due to their higher labour-intensity relative to the goods sector. And workers are demanding higher wages to compensate for higher prices, which in turn could lead to higher prices.

Third, the current surge in wage growth to some degree reflects a catch-up to (energy) inflation. In many countries, at least some wages are indexed to inflation. Some governments (e.g. Germany, France) made one-off inflation compensation payments tax-free. Lower energy inflation will thus automatically drive wage inflation and thus, in turn, services inflation lower. In the Euro Area, a 10ppt swing in energy inflation tends to trigger a 1ppt swing in services inflation with a one-year lag. Between April 2020 and March 2022, Euro Area energy inflation rose by 50ppt, while services inflation rose by 5ppt between June 2021 and April 2023. If the link between energy and services inflation is symmetric, services inflation would fall by 4.5ppt from September 2023 to July 2024, mirroring the 45ppt fall in energy inflation since September 2022. In that case, Euro Area headline inflation, for example, might be well below 2% by that stage.

Summing up

Our first scenario is that the global surge in inflation will result in a ‘soft landing’. Household and market inflation expectations (see Figure 1.6) have risen by 50–150 basis points compared with pre-pandemic levels in advanced economies. In this scenario, central banks have responded adequately and appropriately by raising interest rates, for two reasons:

- First, central banks had to raise policy rates to match the rise in inflation expectations to avoid a real cut in expected borrowing costs. This avoided additional demand stimulus in an economy already suffering at least temporary supply constraints.

- Second, central banks had to insure the economy against a de-anchoring of inflation expectations above the target. In many emerging markets, central banks have less credibility in fighting inflation so they had to act earlier and more aggressively, while in advanced economies, higher credibility allowed a smoother profile.

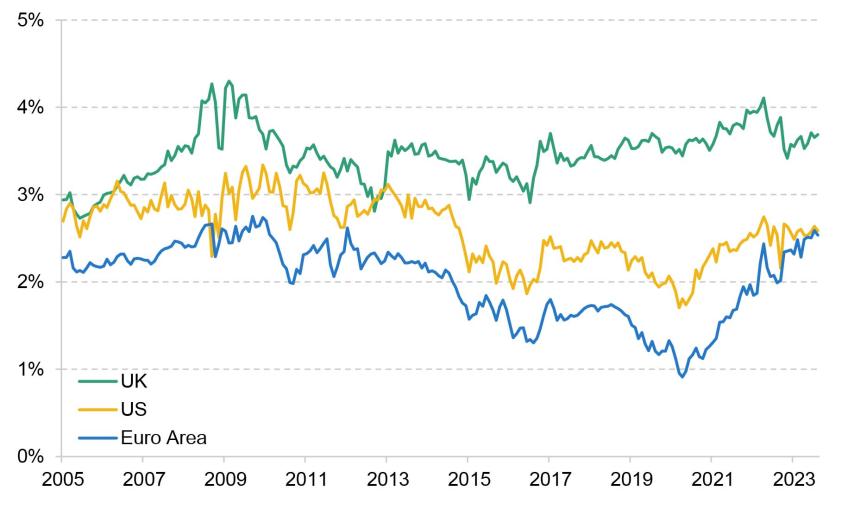

Figure 1.6. Implied market expectation of annual inflation over the five years starting in five years’ time: US, Euro Area and UK

Note: CPI in US and Euro area; RPI in UK.

Source: Bloomberg and Citi Research.

Now, as inflation rates are coming down and upside risks to inflation expectations are fading, central banks can start cutting interest rates back to neutral levels. At the same time, growth should resume or accelerate, because supply constraints are fading. By cutting interest rates at the right time, central banks can revive demand and achieve a ‘soft landing’.

Clearly this is a very delicate balance to achieve. Central banks could easily cut rates too early, before the risk of de-anchoring inflation expectations is banished for good, or too late when the economy is already falling into a recession, which risks central banks returning rates to their lower bounds, powerless to stimulate economies further. We see risks of both scenarios and describe them in the following sections.

1.3 Or will inflation stay for longer?

As long as inflation rates have not fully returned to target with a prospect of remaining there, uncertainty remains about whether central banks have really done enough. Underlying inflation rates remain far above targets in most major advanced economies (see Figure 1.7), labour markets are still tight and growth is resilient in many parts of the world, especially in the US. Is it really enough to wait for fading supply shocks and demand distortions, in combination with the monetary tightening already done, to return inflation to target? And is this happening quickly enough to avoid a further rise in inflation expectations to uncomfortable, de-anchored levels? Or is it premature to call the end of the rate hike cycles and a soft landing of the global economy?

Figure 1.7. Core annual inflation rates: US, Euro Area and UK

Source: BEA and Citi Research.

Tight labour markets

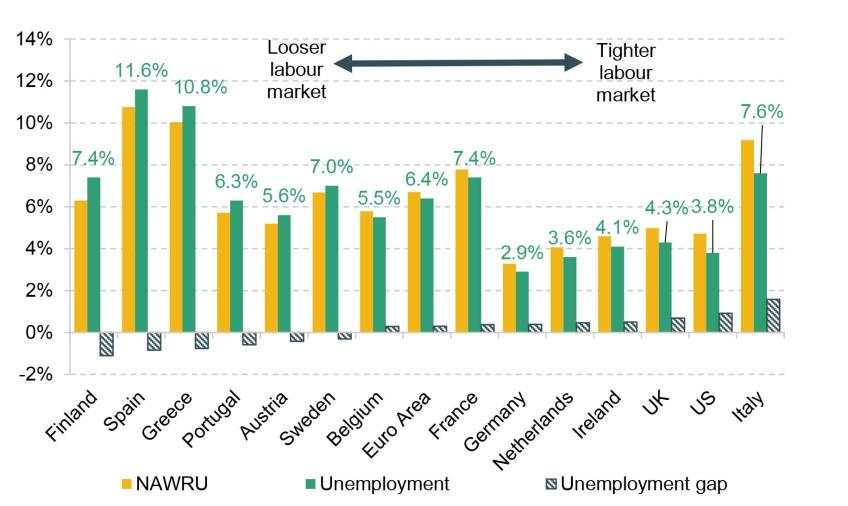

Unemployment rates are at or near record lows in most advanced economies (Figure 1.8). Very low slack in an economy can be a source of inflationary pressures. In addition, it increases the risk that any inflationary surge, whether caused by demand or supply shocks, causes inflation expectations to de-anchor upwards. Unemployment rates were already very low before the pandemic hit in early 2020, but since then, they have fallen even further. In the US and UK, unemployment rates fell to their lowest levels since the 1960s at 3.5% and 3.6%, respectively, in early Spring 2023, but have since rebounded to just under and just over 4%, respectively. Euro Area unemployment fell to its lowest level since the currency zone was formed, at 6.4% in July.

Figure 1.8. Unemployment rates and neutral rate estimates: US and Europe

Source: EU Commission, Eurostat and Citi Research.

In the majority of key western economies, unemployment rates are below the estimates of the non-accelerating inflation (NAIRU) or non-accelerating wage (NAWRU) levels. Labour markets are tight enough to generate inflationary pressures. The EU Commission, for example, estimates that the Euro Area neutral unemployment rate (NAWRU) is currently at 6.7%, 0.3ppt above the latest unemployment rate. For the US, the neutral rate estimate is at 4.7% compared with an August rate of 3.8%, and for the UK at 5.0% compared with an actual rate of 4.3% in June. These neutral rate estimates may be debatable, but inflation and wage growth have indeed surged.

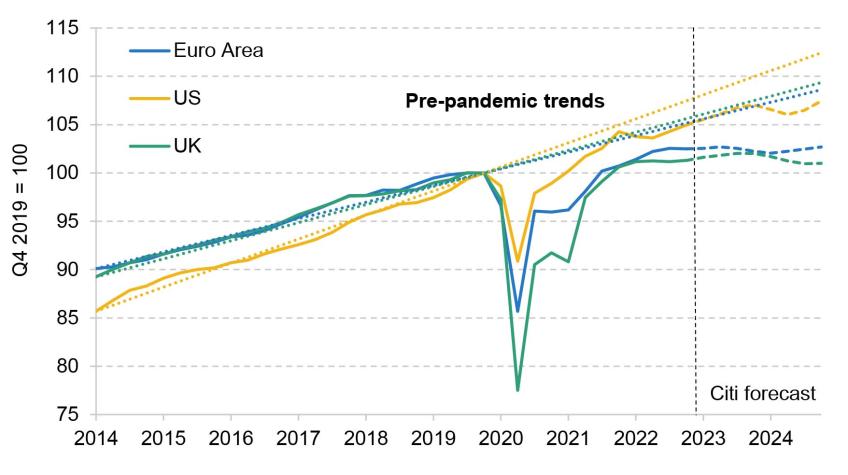

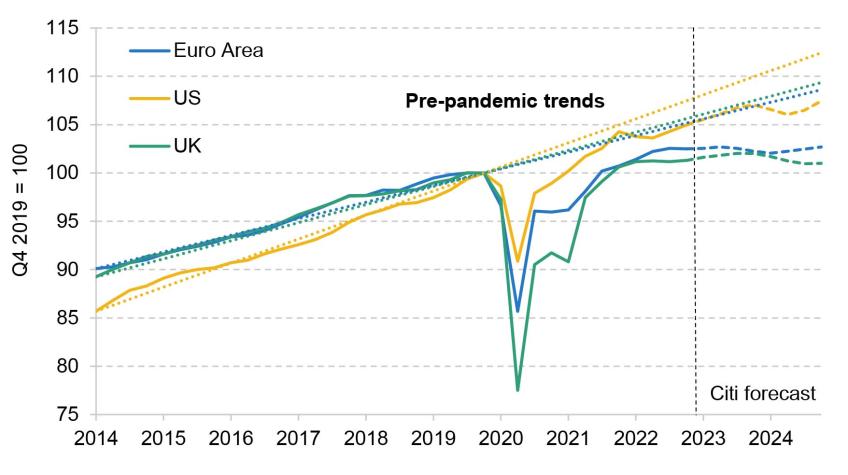

It is striking that these low unemployment rates have been reached despite the fact that, with few exceptions, GDP growth since 2019 has averaged below the pre-pandemic trend and therefore arguably below the pre-pandemic potential (see Figure 1.9). Below-potential growth should lead to a loosening of the labour market, not to a tightening.

Figure 1.9. Real GDP and 2014–19 trend: US, Euro Area and UK

Source: BEA, Eurostat, ONS and Citi Research.

A number of factors can explain this labour market conundrum:

- Drop in labour supply. Especially in the US and the UK, people left the labour force during the pandemic and are now slow to return. This could reflect that the temporary boost in asset prices allowed older workers to retire earlier, but also a growing number of long-term sicknesses, e g. respiratory conditions forcing workers out of their jobs. In the Euro Area, the workforce returned to trend quickly. In fact, to qualify for pandemic support (e.g. furloughing), some workers in the Euro Area might even have left informal work arrangements and bolstered the registered labour force. Sick leave levels are still very high in some parts of the Euro Area.

- Labour hoarding. Output per worker has dropped mostly in sectors that faced weak demand during the pandemic, such as transportation and hospitality. Employers may have hung on to some workers despite a lack of activity for fear of missing out on an activity surge when demand normalised. This may have been helped by low interest rates allowing firms to cover temporary losses at low costs, but also by surging prices which allowed them to raise margins. On a forward-looking basis, hoarding may now migrate to the manufacturing sector where hiring has not slowed as much as plunging demand would suggest.

- Labour-intensive services-led growth. Hoarded labour may not be enough to absorb all of the rebound in services activity. For example, in tourist hotspots such as the Mediterranean, many new workers had to be hired. Many of the workers who would normally be available for summer work in hotels may now be tied up elsewhere, however – for example, in the health sector.

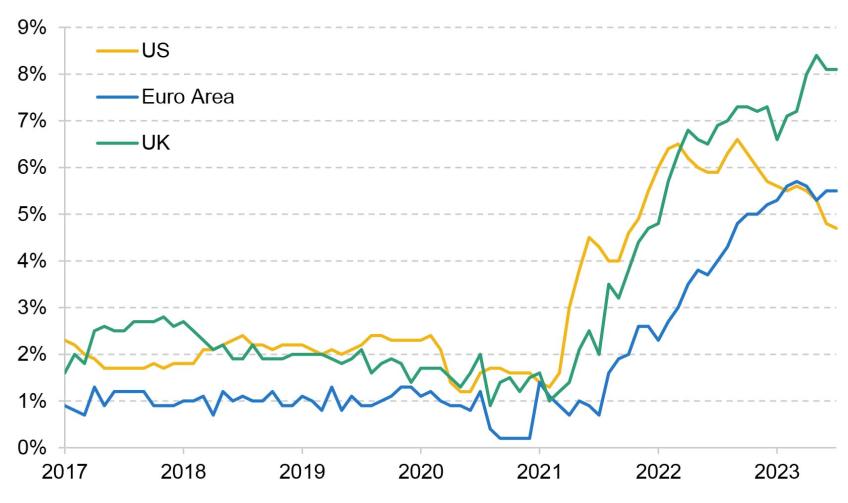

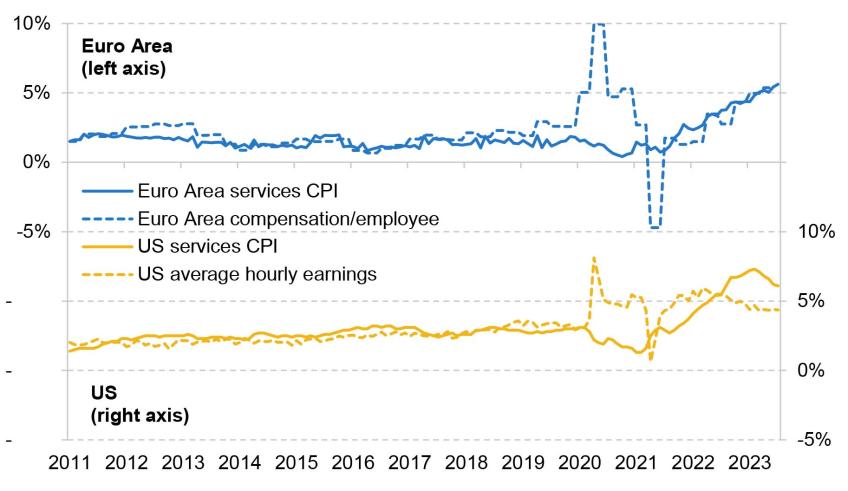

Some of these factors may turn out to be temporary, others permanent. In the meantime, however, tight labour markets are likely to have contributed to the surge in global wage growth. In the UK, average weekly earnings growth has surged to nearly 8% year-on-year in Spring 2023; in the Euro Area, compensation per employee was rising by nearly 5% in Q1; and in the US, average hourly earnings growth seems to be settling at around 4.5% year-on-year (Figure 1.10). These levels are far higher than trend productivity growth of around 1%, and thus boost unit labour costs and, on an ongoing basis, would not be consistent with target rates of inflation.

Figure 1.10. Annual wage growth: US, Euro Area and UK

Source: BLS, ONS, ECB and Citi Research.

Strong wage growth does not have to be an inflation concern. For example, it can be absorbed by falling profit margins or by rising productivity growth. However, neither has been the norm in recent decades, so that wage growth and services inflation (the part of the consumer basket with the highest labour content and therefore wage exposure) have usually moved in lockstep in both the Euro Area and the US (Figure 1.11). That the relationship seems to have broken down at least in the US more recently may be due more to the violence of swings in productivity than to a fundamental decoupling of wage growth and services inflation. Unless there is an ongoing income distribution process from capital to labour, without a return of wages to target-consistent levels of around 3%, services inflation and therefore also overall inflation may not return to target either.

Figure 1.11. Annual wage growth and services inflation (year-on-year %): US and Euro Area

Source: BLS, ECB and Citi Research.

There is some evidence that job creation is slowing in the US and the Euro Area, but not yet enough to lead to a build-up in slack which would in turn weigh on wage growth. Indeed, the European Central Bank forecast in June that with the market-implied policy path, the Euro Area unemployment rate would continue to edge lower by 0.1ppt per year, marking new all-time lows on the way. Also in June, the Federal Reserve forecast the US unemployment rate to rise somewhat from below 4% to slightly above in 2024 and 2025.

Factors supporting growth

A range of factors could support growth in the coming quarters and delay the emergence of slack and therefore delay the normalisation of wage growth and inflation.

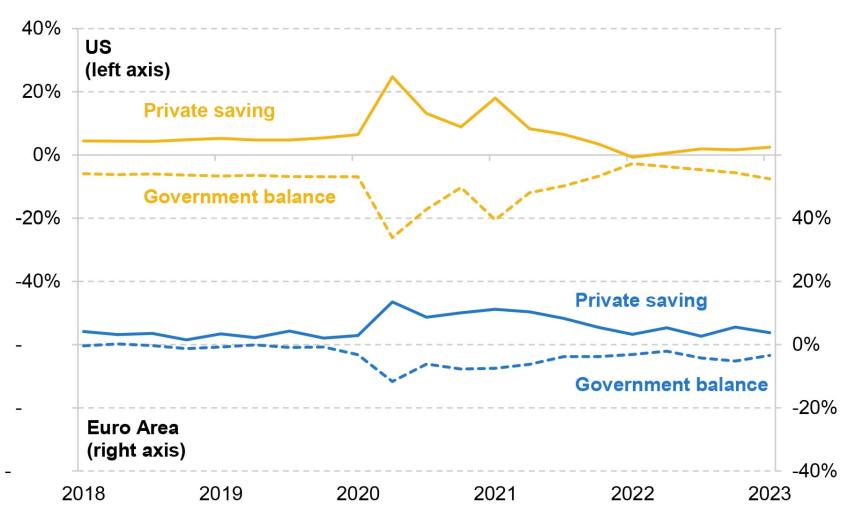

- First,fiscal policy is not substantially restrictive in many advanced economies. Budget deficits may be falling, but that largely reflects the phasing-out of subsidies to households and businesses to help with pandemic consequences and high energy costs. Since both factors have diminished, phasing out the support should be demand-neutral. In addition, some investment programmes, such as the EU’s NextGenerationEU programme or the US Inflation Reduction Act, carry on. Finance ministers’ 2024 budgets are mostly neutral or slightly restrictive. This is helped by the fact that many governments have lengthened the maturity profile of their debt during the low-interest-rate period and are therefore not immediately impacted by the rise in short-term borrowing costs.

- Second, central bank balance sheets support growth. Central banks inadvertently counteracted the maturity lengthening of government debt by buying up large amounts of bonds since 2008, essentially swapping long-term bonds into overnight borrowing from banks. Those purchases were funded by the creation of reserves at the central bank (typically) remunerated at the central bank policy rate. Now that market interest rates are rising, this is leading to large central bank losses. The value of the bonds is falling (although most central banks do not mark to market), while the interest payments on reserves are soaring. The potential impact is significant. Bank reserves at the central bank amount to 20% of GDP in the US, 26% of GDP in the Euro Area, 58% of GDP in Switzerland1 and 92% of GDP in Japan. With interest rates on these up more than 5ppt in the US, 4ppt in the Euro Area and almost 3ppt in Switzerland (although so far not at all in Japan), and with limited matching increase in interest income on the bonds purchased during the quantitative easing (QE) period, the outflows to banks (and thus ultimately to the private economy) could easily be worth around 1% of GDP. With the notable exception of the UK, central banks cannot automatically pass on these losses to finance ministries. Instead, they are starting to accumulate negative equity positions which they will then recover over time by cutting the dividends they pay to finance ministries. In the meantime, however, central banks fund their losses by monetising public debt or ‘printing money’. Central banks are partly responding by reducing the size of their balance sheets or stopping interest payments on some reserves,2 but the process is not quick enough to stop the outflow immediately.

- Third, the large fiscal response to the pandemic is still supporting growth. During the pandemic, households and companies built up enormous savings, which mirror the deficits of government (see Figure 1.12). In nominal terms, these savings are still large now and support spending, although in many places, such as the US, saving rates have plunged below pre-pandemic levels, suggesting that some dissaving is going on. Once that stops, normalisation will ultimately start weighing on spending. This could be offset by ongoing public investment programmes created in the wake of the pandemic, such as the EU’s €800 billion NextGenerationEU programme or the US Inflation Reduction Act.

Figure 1.12. Government balance and private sector net saving (% of GDP): US and Euro Area

Source: BLS, Eurostat and Citi Research.

Summing up

It is plausible, in our view, that central banks and markets underestimate the persistence of the inflation surge. Underlying inflation rates remain above target in most advanced economies, and while central banks have raised interest rates, demand growth is not slowing everywhere. In the US, for example, GDP growth seems to be accelerating recently rather than decelerating (see Section 1.5). Labour markets remain tight, wage growth elevated.

Some of the supportive factors, such as pent-up savings and legacy fiscal support, may wane eventually, but there is a risk that they boost growth long enough for households, firms and government to get used to high inflation. The absence of slack means central bankers have less room for manoeuvre to look through temporary shocks, as former Bank of England Governor Mark Carney explained in his 2017 ‘lambda framework’ on the Bank’s reaction to the EU referendum (Carney, 2017). If inflation fails to come down and slack does not rise, central banks may have to keep rates high for longer or even hike further than markets or central bankers are currently anticipating until growth slows enough to rebalance demand and supply, which would most likely involve a significant recession or ‘hard landing’.

1.4 Or has monetary policy overreacted?

Even though most central bankers will not acknowledge it in their quest to return inflation to target, there is also a significant risk that they will go too far. In fact, monetary tightening may have gone too far already, which may show not just in deep recessions but also in permanent losses of income. We see at least three areas of concern.

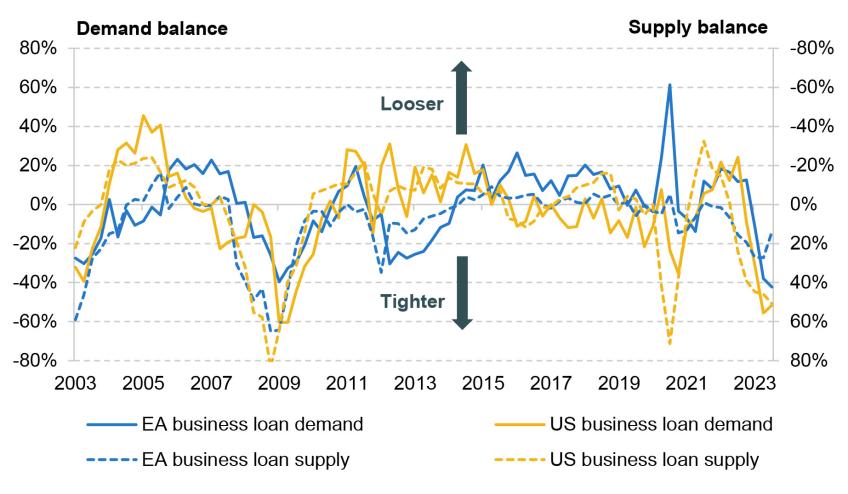

Credit tightening

First, there are signs of a significant tightening in credit demand and supply. The sharp rise in interest rates has triggered a sharp drop in loan demand by households and businesses. Business loan demand in both the US and the Euro Area was contracting at the fastest pace since 2008–09 this summer according to central bank surveys of banks. For a tense moment in March of this year, when several US regional banks failed, it also looked like credit supply could be subject to a rather violent tightening. However, unlike in 2007–08, US authorities managed to bring the crisis under control. Still, credit supply was still tightening at a much more rapid pace in the US than in the Euro Area, which has not experienced a similar crisis so far. In fact, in the Euro Area, the pace of credit supply tightening appeared to ease in the summer (Figure 1.13). Citi estimates suggest that both economies are set to face credit impulses usually associated with a 1–2% drop in GDP versus the baseline 12–18 months later (Sheets, Sockin and Langlois, 2023).

Figure 1.13. Business loan demand and supply: US and Euro Area

Source: ECB’s Bank Lending Survey, Federal Reserve’s Senior Loan Officer Survey and Citi Research.

So far, higher interest rates and tighter credit conditions have not led to a major increase in bankruptcies. Excess savings from the pandemic may help companies avoid insolvency for the time being. However, EU-level data suggest some acceleration in bankruptcies in financially more challenged economies such as Spain (although national data paint a less worrying picture). Besides compounding weaker credit supply via the losses incurred by banks, rising bankruptcies, if they occurred, could also quite suddenly trigger mass redundancies.

Slowing growth

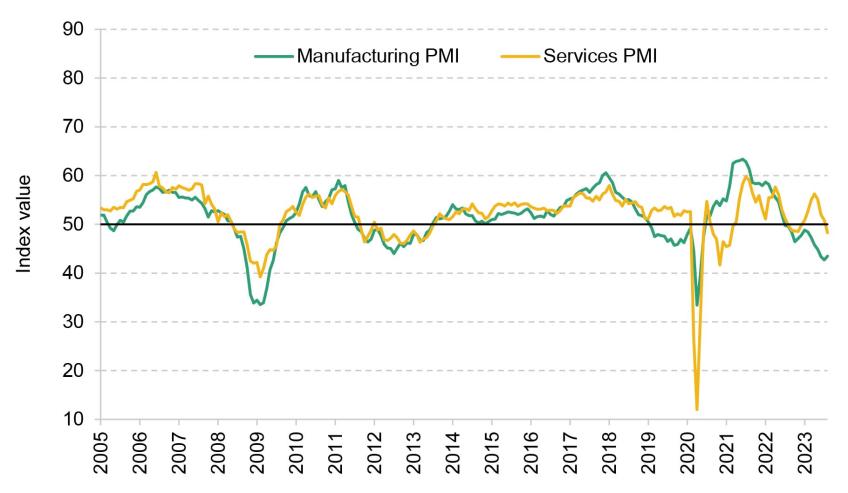

Second, there are already signs that economic growth is slowing sharply in some regions and sectors. For example, the global manufacturing Purchasing Managers’ Index (PMI) has been in contractionary territory since September 2022, and in the Euro Area in particular, manufacturing PMIs are at lower levels than during the 2011–12 sovereign debt crisis (see Figure 1.14). More recently, the global services PMI has also slowed as weakness spreads from manufacturing. The labour-intensive services sector is much more critical for job markets than manufacturing and could bring the surprising resilience in hiring to an end.

Figure 1.14. Purchasing managers’ indices: Euro Area

Note: A value greater than 50 represents an expansion.

Source: S&P Global and Citi Research.

Fiscal retrenchment

Third, governments may be forced to retrench due to political blockades or restrictive fiscal rules.

- In the US, Congress has been split since the mid-term elections, with a Republican majority in the House of Representatives and a Democratic majority in the Senate. The Biden administration passed the important Inflation Reduction Act just before that and was able to get the debt ceiling raised until after the 2024 presidential elections, but fiscal room is now severely constrained.

- In the Euro Area, fiscal rebalancing will only start in earnest in 2024 as governments phase out their energy price support packages and remaining pandemic support (see Figure 1.15). This is likely to be neutral for growth as the fiscal tightening is offset by the reversal of the terms-of-trade shock, just like the US tightening in 2022 was largely neutral as it was offset by the end of health policy measures. However, Euro Area governments will – at least to some extent – also be constrained by the reinstatement of the currency union’s fiscal rules. There is an ongoing debate on how the rules will be implemented, but in particular the rule limiting member states’ borrowing to 3% of GDP will not change given that it is written in the EU Treaty. On current plans and projections, most major Euro Area economies will miss the target in 2024, suggesting a risk that they will come under some EU Commission tutelage (excessive deficit procedure) to precipitate fiscal rebalancing.

Figure 1.15. Fiscal impulse (% of GDP): selected economies

Note: The fiscal impulse is here defined as the change in the cyclically adjusted government balance. A positive figure indicates a fiscal expansion, and a negative number a fiscal tightening.

Source: National statistical offices and Citi Research.

Summing up

Our third scenario is that central banks have overreacted to an ultimately temporary supply shock. Growth and labour markets may look resilient for now, but monetary policy famously works with long and variable lags. Although so far banks and the wider financial system have proved more resilient than in 2008, the credit cycle is cooling at its fastest rate since then. Having overshot their inflation targets for a protracted period of time, central bankers may now lean towards tolerating undershoots in order to restore lost credibility. That makes overtightening a likely, perhaps even intended, outcome. The fact that key economies such as the US are holding up relatively well despite the unprecedented rate hike cycle could be misleading, and a hard landing could already be baked in the cake, as central bankers will be late to react to inflation undershooting target.

If central banks have gone too far, economies might be heading for deep recession and a sharp fall in inflation rates over the coming year. Even a return of the deflationary tendencies of the pre-pandemic period cannot be ruled out. That could return central banks to the effective lower bound of their policy spectrum and thus being unable to stimulate the economy. If fiscal policy also fails to respond, a return of ‘secular stagnation’ is plausible.

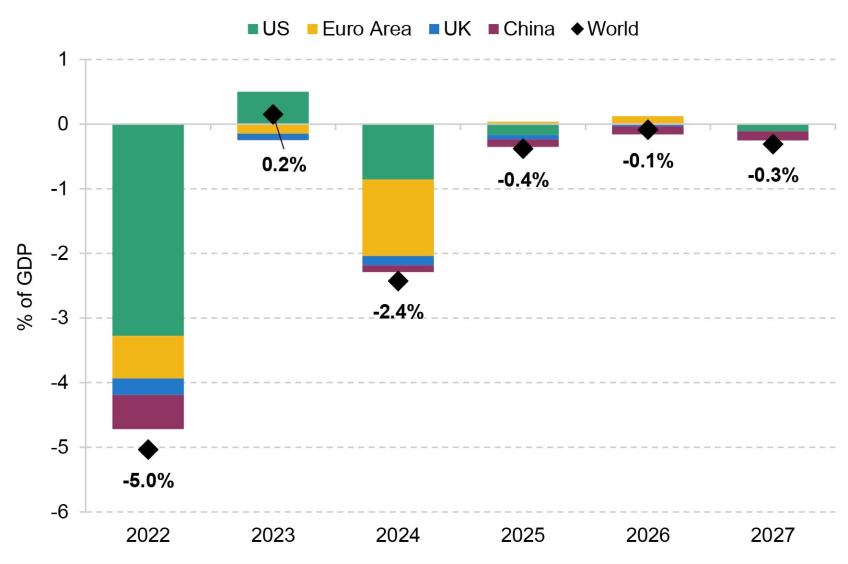

1.5 Regional outlook: too much tightening or too little?

Having outlined the three key scenarios, we now turn to where they might be most likely to play out. Global growth and inflation swings over the past few years were largely driven by common factors such as the pandemic and the policy response to it, or the repercussions of Russia’s military attack on Ukraine. And the starting point going into the crisis was ostensibly similar across many major economies after an extended period of low but stable growth, low unemployment, low inflation and low interest rates. However, by now, cyclical positions in the world’s largest economic blocs – the US, China and the EU – are different. So too, therefore, are the potentially narrow paths to a soft landing and sustainable growth with inflation at target. For different reasons, we expect very weak growth in the world’s largest economies in 2024, with global GDP growth slowing from an already weak 2.3% this year to just 1.7% next. Excluding China, growth may be below 1% and thus fulfil some definitions of a global recession and a ‘hard landing’. But within that, the balance of risk between overdoing the fight against inflation or not doing enough is tilted in different directions, in our view.

US: more likely to have not tightened enough

Since March 2022, the US Federal Reserve has hiked its policy rate from 0–0.25% to 5.25–5.5%, the most extensive rate hike cycle since the late 1970s. The level of policy rates in real terms is similarly high to that in 2007. On any measure, US monetary policy is restrictive and got there faster than in a very long time. However, so far, the recession that usually follows such a tightening, and has been signalled by the inverted US yield curve for nearly two years, has not materialised.

Despite resilient growth, inflation dynamics seem to be normalising. Headline annual inflation fell from a peak of more than 9% in June 2022 to 3% a year later before rebounding due to the latest rise in oil prices. Core inflation has been steadily receding from a peak of 6.6% in September 2022 to 4.3% in August 2023 and seasonally adjusted three-month annualised inflation excluding energy dropped to 3% in August, suggesting further declines ahead. The labour market is showing signs of loosening, with monthly jobs growth averaging just 150,000 over the summer, normally consistent with stable unemployment. A rebound in participation has actually raised the unemployment rate from a trough of 3.4% in April to 3.8% in August 2023. The US could be on track for a soft landing.

However, there are also some concerning signs, which could suggest the Fed has not done enough: wage growth troughed at 3.7% on a three-month over three-month annualised basis in April, above the 3% level consistent with 2% inflation and 1% productivity growth, and has been accelerating to nearly 5% again over the summer. GDP growth seems to be accelerating, with strengthening demand spreading from the services sector to goods spending.

For now, we still expect US GDP growth to weaken, including a recession in Q2 and Q3 2024, and inflation to return to target. GDP growth should slow sharply from 2.1% in 2023 to just 0.3% in 2024, before rebounding to 2.4% in 2025. We expect the Fed to raise rates until reaching a terminal policy range of 5.5–5.75% and then to cut rates from Q2 2024. However, risks are skewed towards upside surprises on growth and inflation and more persistent policy restriction. While the bar for the Fed to react with even higher policy rates is high, interest rates may stay high for even longer than markets, households and firms currently expect. It may still take a significantly deeper recession than we currently predict to return price stability in the US.

Given the deep political divisions in the US, uncertainty around upcoming 2024 US presidential elections could already have an impact on the economic outlook before the vote takes place. However, the impact could be larger on the rest of the world than on the US itself, given the outsized role of the US President in foreign policy and the potentially very different world views leading Republican contenders have from the current administration. A Republican administration could once again focus on balancing bilateral US trade relationships and reduce or withdraw security support for its allies, in particular in Europe.

Euro Area: more likely to have overtightened

The Euro Area economy remains in the cross-currents of the pandemic aftermath, the war in Ukraine and aggressive monetary tightening. Over the past year, both manufacturing and services activity were bolstered by pent-up demand from the pandemic, but restrained by a lack of supply, causing some inflationary pressures. However, this pent-up demand has increasingly run its course. The energy crisis triggered by Russia’s war in Ukraine eroded real incomes and corporate margins, and while Europe has made progress in weaning itself off Russian energy and the risk of supply disruptions is lower, energy supply could be permanently more uncertain and more expensive than previously expected.

In the face of these repeated large shocks, the Euro Area economy was surprisingly resilient in the first half of the year. And with rising wage growth, a resilient labour market and falling inflation underpinning real income gains for households, the European Central Bank (ECB) and the EU Commission see the chance of a pick-up in activity. Unfortunately, however, there is no sign yet that growth is picking up. On the contrary, economic sentiment – for example, the purchasing managers’ indices – has fallen into recession territory and ‘hard data’ such as retail sales, trade or industrial production also show an economy shifting into reverse. We expect the economy to shrink moderately for the rest of this year and early next year, and to struggle for momentum thereafter. That yields 0.3% GDP growth this year, –0.1% in 2024 and 1.2% in 2025.

The growth weakness could be blamed on the ongoing impact of last year’s energy shock, China’s disappointing reopening and the globally weak manufacturing cycle. More recently, the headwinds seem to be spreading from the trade- and investment-exposed manufacturing sector to the larger and more labour-intensive services sector. And while wage growth has accelerated and the labour market remains resilient with unemployment at all-time lows, growing economic uncertainty may also start to undermine consumer confidence. Inflation has halved from double-digit territory, and the seasonally adjusted annualised Harmonised Index of Consumer Prices (HICP) excluding energy at 4% in July suggests further declines ahead. However, although wages are now rising faster than prices, households may hold back on spending.

The European Central Bank reacted to the sharp rise in inflation to 10% in late 2022 first by phasing out its asset purchases, then by hiking the policy rate from –0.5% to +4% between July 2022 and September 2023. And while progress in the fight against inflation and weakening growth (as well as the sheer cost of rate hikes for the ECB, as it pays interest on 3.7 trillion of bank reserves but does not generate much extra income on its €5 trillion portfolio of bond purchases) probably mean that the bar to more ECB rate hikes is now very high, the ECB’s focus on spot inflation makes imminent rate cuts unlikely. In fact, the ECB may tighten monetary conditions further by accelerating the run-off of the asset portfolio in the coming months (most likely by ending reinvestments of its €1.7 trillion pandemic emergency purchase programme).

With the economy already shrinking and the ECB still tightening policy, the risk of overtightening seems significant. The ECB twice made similar errors when it was the last major central bank to hike before the global financial crisis in April 2008 and also while the Euro Area sovereign debt crisis brewed in early 2011. Inflation and wage growth are high, but are lagging variables of the economic cycle. Overtightening is particularly dangerous in the case of the Euro Area as low potential growth and a low real neutral rate pose the risk that the ECB could quickly run out of room to stimulate the economy. In addition, high levels of public debt and strict fiscal rules could also curb the ability of fiscal policy to stimulate the economy, just like they did before the pandemic.

China: necessary belt-tightening or ‘Japanification’?

China is facing an altogether different challenge from the US or Europe, with growth and inflation too low rather than too high. The economic situation of the world’s second-largest national economy looks increasingly concerning. After just 3% real GDP growth in 2022, as the government continued to pursue a zero-COVID policy, the economy accelerated somewhat in early 2023 after public health measures had been phased out, with near 9% annualised growth in Q1. However, in the spring, the economy slowed again to 3.5% annualised in Q2.

It is plausible that China’s potential growth rate is falling. Productivity gains are harder to achieve as the economy matures and demographic factors increasingly limit the supply of new workers. The economy has built-up imbalances – for example, in the real estate sector and in local government finances. Total economy (public and private) debt is rising incessantly and reached nearly 300% of GDP last year. One view is that China needs belt-tightening to ensure a gradual return to more sustainable debt levels.

An alternative view, however, is that Chinese authorities are running excessively tight policy. Given falling CPI inflation, Chinese policy rates rose by around 250bps between September 2022 and September 2023 in real terms, even though the economy has slowed. Unemployment, especially youth unemployment, was rising sharply before authorities stopped publishing data. Producer prices have been in deflation for a while, and most recently consumer price inflation has followed. By failing to respond decisively, the People’s Bank of China risks ‘Japanification’, where low inflation and wage growth render monetary policy powerless to stimulate the economy.

In this environment, Chinese activity growth is expected to remain disappointing. We forecast 5.0% GDP growth for 2023 and 4.6% for 2024.

1.6 Citi forecasts, then and now

Every year, the IFS Green Budget is an opportunity to look back at forecast performance. In the Green Budget 2022 we warned that growth would slow sharply – and it did, albeit not by as much as feared. Real global GDP growth at current exchange rates ended 2022 at 3.1%, 0.2ppt higher than we had forecast, but is currently projected to have slowed to 2.3% this year, also 0.2ppt higher. Especially for advanced economies, we were too pessimistic, with the US on track for 2.1% growth this year instead of 0.7%, the Euro Area for +0.3% instead of –0.4% and the UK for +0.5% instead of –0.5%. Japan is the outlier, with GDP growth accelerating from the disappointing 1.0% pace in 2022 to 1.3% in 2023. We were too optimistic for China, where the economy is struggling to build momentum despite the government abandoning the zero-COVID policy a bit earlier than expected at the end of last year. Official growth is now on track for just 5.0% in 2023, 1.1ppt less than we forecast last year. For the other major emerging markets (EMs), such as India and Brazil, we are now much more optimistic than last year.

In 2022, we forecast global inflation to fall from 7.1% in 2022 to 5.7% in 2023 and 3.5% in 2024 before converging with the 3% long-run average thereafter. Superficially, that forecast remains on track, with our latest projections at 7.0%, 5.6% and 4.4%, respectively, and then still down to 3% for the remainder of the forecast horizon. However, this is flattered somewhat by a more-rapid-than-expected drop in commodity prices and conceals that ‘underlying inflation’, i.e. inflation rates excluding food and energy, has generally been much more persistent than expected.

Higher-than-expected growth and underlying inflation also explain why central bank peak rates are now expected to be significantly higher than forecast last year. For the US Federal Reserve and the Bank of England, we now see the peak rate at 5.75% and 5.25%, respectively (previously 5.0% and 4.25%, respectively) and for the European Central Bank at 4% (previously 2%). With the rate hike cycles now mostly over (we expect only one additional 25bps step at the Fed and none at the ECB and the Bank of England), the uncertainty is now shifting to the persistence of these restrictive rates. We expect the Fed, the ECB and the Bank of England to start cutting their policy rates in Q2 2024. The Bank of Japan has remained an outlier, keeping its yield-curve control in place beyond the end of Kuroda’s term, but that looks increasingly likely to change this winter. By 2026, we expect the Fed to have settled at policy rates of 2.5%, and the ECB and the Bank of England at 2.0%. Note that some EM central banks in Asia and South America have already started cutting rates, while the People’s Bank of China is cutting without ever having hiked.

Table 1.1. Real GDP growth forecasts, Green Budget 2022 and Green Budget 2023

Source: IFS Green Budget 2022, and Citi Research forecasts as of 20 September 2023.

1.7 Conclusion

The path to a soft landing of the global economy after the inflation surge and sharp rate hike cycle of the past two years is narrow. In the US, growth and inflation are so resilient that the Federal Reserve might be at risk of struggling to return inflation to target quickly enough, which could trigger the need for even more tightening later on. China’s economy is struggling to gain momentum and may be exporting deflationary tendencies to the rest of the world. In Europe, economies are struggling to grow even before the full impact of monetary policy has unfolded. If the European economy falls into a protracted recession, and deflationary tendencies return, the ECB would need to react quickly and decisively to avoid returning to the effective lower bound.

Excluding China, we are now forecasting world GDP growth of less than 1% in 2024, fulfilling some definitions of a global recession. And for China we are not optimistic either. Such weak growth should force underlying inflation lower, albeit not quickly. Volatile energy and food prices could prevent a return of price stability, in either direction. Still, by the time of the 2024 Green Budget, global central banks will likely be well into a rate-cutting cycle.

Risks to this scenario abound. On the positive side, falling inflation may spur growth more strongly than we currently expect. The manufacturing cycle could be turning as inventories are depleted. Public investment to accelerate the green transition and digitalisation may increase demand, and technological developments such as artificial intelligence (AI) could boost supply.

On the negative side, inflation may not easily return to target, even in weak economies, or may even rebound where growth remains too strong. It may take an even deeper slowdown to break inflationary pressures for good and that may in turn mean much higher policy rates for an extended period. This risk seems particularly pertinent in the US. However, global trade fragmentation, the consequences of the pandemic for labour supply sanctions, energy supply problems or climate change could keep inflation high even in weak economies. They would simply not be weak enough.

In contrast, for many other parts of the world, it is also possible that central banks have already gone too far. As the monetary headwinds strengthen, they may trigger new recessions or deepen and extend existing ones as credit supply and demand dry up. Government may be unable to help amid high debt ratios and borrowing costs, while central banks are unable to come to the rescue as they keep one eye on the Fed and financial stability. While such risks seem more pertinent in emerging markets, even western Europe may not fully resist this drag.