The new state pension has many good features. Reforms legislated in 2007 and 2014 mean the vast majority of working-age individuals who have always lived in the UK will get the full amount, currently £203.85 for those reaching the state pension age after April 2016.

This new system is relatively simple. The pension can be received from a single age, it is not means-tested, and we are moving away from providing bigger state pensions to middle and higher earners.

Despite this simplicity, there remains a lack of confidence in the system.

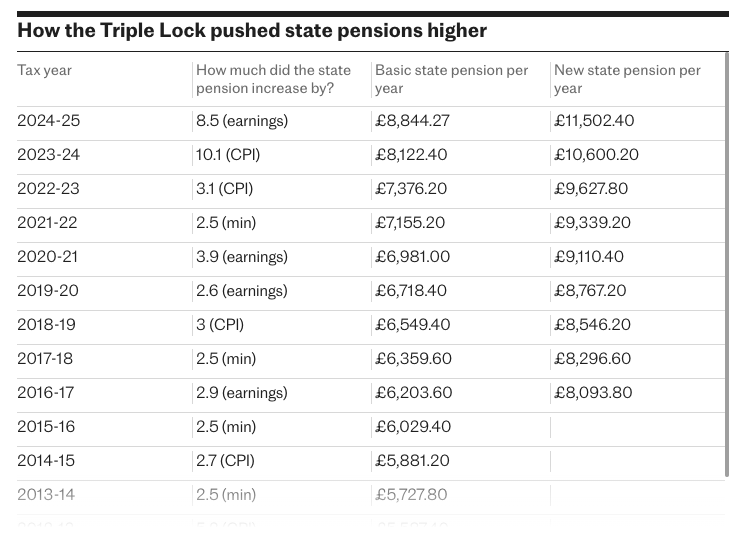

Four-in-ten adults do not think it will keep pace with rising prices over the next decade. That’s despite the fact it has increased at least as fast as inflation every year since 1975 and despite the “triple lock” which ensures state pensions rise in line with the largest of inflation, earnings, or 2.5pc.

The triple lock – and the introduction of the new state pension in April 2016 – have increased the value of the flat-rate part of the state pension dramatically.

The current £203.85 a week is certainly not a princely sum and most will want to save privately for a better standard of living in retirement. But at 30pc of average earnings it is bigger than at any point since 1968 and forms a key part of retirement income right across the income distribution.

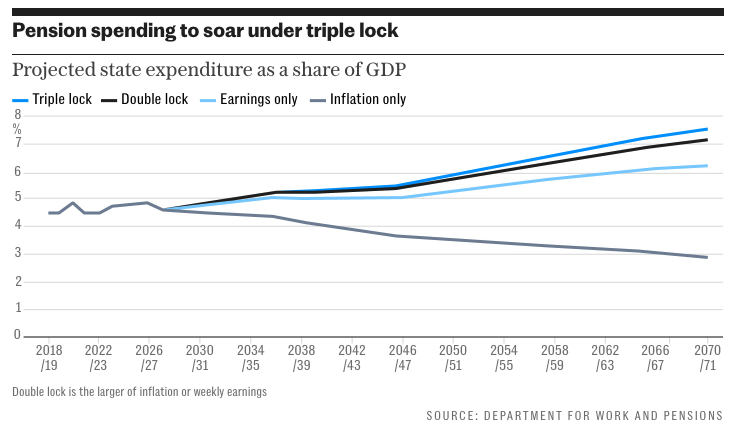

For those who want a more generous state pension over time, the triple lock will deliver this. But the mechanism delivers a boost relative to earnings only when the economy is struggling.

Bad economic times since 2011 led to the triple lock pushing up the state pension by 60pc, whereas prices and average earnings have increased by around 40pc. But were we – and let’s hope we do – to enter a prolonged period of strong and stable economic growth, then under the triple lock the state pension would increase no faster than earnings.

We can do better. What is needed is for politicians to state what share of average earnings they think the state pension should be and then legislate a pathway for getting there.

This is precisely what the Government has done with the minimum wage. If we want, this could be a path to a more generous pension.

For example, going from 30pc to one-third of full-time average earnings would deliver a state pension that in today’s terms was £230 per week, or £26 higher, than it is now.

But by 2050, it would cost an additional £18bn per year – equivalent to an additional 2p on the basic and higher rates of income tax. And that cost would come on top of the strains to the public finances from having 25pc more pensioners than today.

Having reached our desired level of state pension we should adopt the same method for increasing it as is done in Australia.

This guarantees that over the longer-term it grows in line with average earnings, so that pensioners share in rising living standards.

It also ensures that it always increases each year by at least inflation, so that pensioners are protected in downturns. This system would deliver many of the benefits of the triple lock.

But, unlike the triple lock, having protected pensioners from recessions it would not reward them during recoveries. By delivering greater certainty over the value of the state pension – and how much it would cost – we can help ensure people can have confidence over the state pension as a future source of income, protect them from poverty, and provide a bedrock on top of which they can build private pension savings.

This article was first published in The Telegraph and is reproduced here with kind permission.