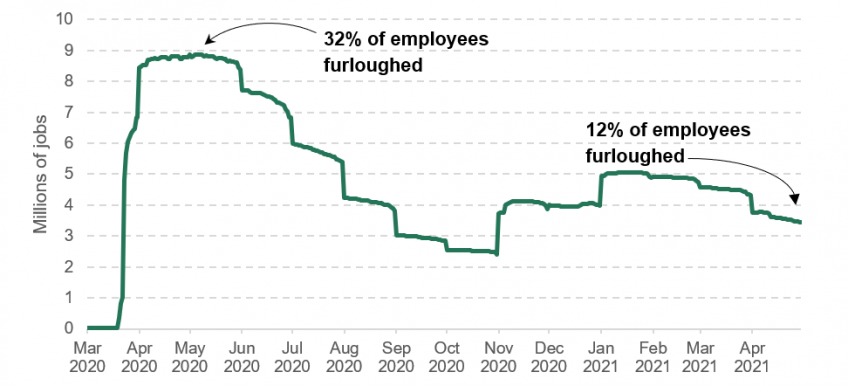

Tomorrow, the government will start to wind down the Coronavirus Job Retention (furlough) scheme. The latest data – from the end of April – showed that there were still 3.4 million jobs on furlough, representing around one for every eight employees (Figure 1). Some groups are especially likely to be furloughed: those aged under 25 or over 65, Londoners, women, and workers in the cultural, accommodation, or food sectors. While the number furloughed will have fallen as the economy has continued to re-open, it is likely that millions of people and their employers will be affected by the phasing out of the furlough scheme. The Office for Budget Responsibility expect that while the total gross outlay on the furlough scheme peaked at £10.1 billion in May 2020, it was still running at £2.2 billion in June 2021.

Since last March, the government has paid 80% of the salaries of employees (up to a maximum government contribution of £2,500 per month) – with the employers only having to pick up the (small) bill for employer National Insurance and pension contributions since last August. The big change on July 1st is that the government will only pay 70% of the furloughed employee’s salary, so the employer has to pay (at least) 10% of the salary themselves. In August and September, the Government plans that employers will have to pay (at least) 20% (with the government picking up 60%). For a furloughed employee previously earning £20,000 per year, the cost to an employer of keeping them will rise from £155 per month in June, to £322 in July and £489 per month in August and September, after which the scheme is due to end. With the cost of keeping employees on furlough rising, we therefore expect to see rising redundancies over the summer even before the final end of the scheme.

The wind down of the furlough scheme represents a step towards ‘normality’ in the labour market, but it also will mean big income losses for many of those who end up unemployed unless they are swiftly able to find alternative employment. In this observation we discuss the kind of support available for such workers via other programmes, and what sort of hit to their income they might see if they do lose their jobs.

Figure 1: Number of jobs furloughed

Notes: The share of employees furloughed is calculated as the number of jobs furloughed divided by the number of employees at that time. This will be a slight overestimate as some people have multiple jobs. This means that some can be furloughed from more than one employee job; or class themselves as self-employed, but be furloughed from a (second) employee job.

Source: HMRC, Coronavirus (COVID-19) statistics; ONS, Labour market overview, UK: June 2021.

The main alternative form of support for those who lose their job comes from Universal Credit (UC), a means-tested family benefit (in other words, entitlement is higher for poorer families). In the wake of the pandemic, the government made a high profile £20 per week increase to UC – equivalent to about 13% of claimants’ entitlements on average, and at a cost of around £½ billion per month. But that expansion is due to finish at the same time as furlough at the end of September.

The bigger picture is that UC provides a very different kind of support to furlough. UC is designed to prevent family living standards falling too low, rather than providing earnings replacement to employees who have lost their job per se. In practice, this means that while the furlough scheme provided 80% replacement (up to a cap) of pre-furloughearnings regardless of other circumstances, UC takes into account current earnings, the earnings of any partner, family assets, number of children, and rent, in order to target support at those in particular need.

This means that the kind of income drop that an individual might experience as they move from furlough to unemployment varies enormously.

This can be seen in Table 1, which shows how much support the government provides via furlough and the benefit system, for four example individuals who are furloughed when the scheme is available and unemployed when it is not.

When the furlough scheme ends, a single individual who pre-furlough earned £20,000 per year, has no children and owns their own home (person 1) has a UC entitlement of less than a quarter of their (pre-tax) furlough payment.

Conversely, an otherwise identical lone parent renter (person 2) sees their support fall by ‘only’ a third – because of their higher needs (housing costs and children). They are able to receive UC even when furloughed and UC makes up more of their lost earnings when the furlough scheme ends.

But if that same person had a high-earning partner (person 3), they would not be entitled to UC at all – because it is based on family earnings, so they are assessed as having too high an income (the same would be true for a person with significant assets). They would be likely to be eligible for ‘new style’ Jobseeker’s Allowance, providing the same level of support that person 1 receives, but only for six months (whereas person 1’s entitlement would be indefinite).

The case of person 4 illustrates the (ir)relevance of pre-furlough earnings. This individual is identical to person 1, except she earned £37,500 per year. When on furlough, this entitles her to the maximum furlough payment of £30,000 per year – almost double what person 1 receives. But when she becomes unemployed, her prior earnings make no difference to her UC entitlement, meaning that she ends up on the same amount as person 1 – which represents just £1 for every £8 she received in furlough.

Table 1: Furlough, Universal Credit and Jobseeker’s Allowance entitlements for example individuals whose employer has no work for them

| Person 1 | Person 2 | Person 3 | Person 4 |

Characteristics |

|

|

|

|

Pre-furlough earnings (p.a.) | £20,000 | £20,000 | £20,000 | £37,500 |

Partner? | No | No | Yes | No |

Partner's earnings (p.a.) | N/A | N/A | £50,000 | N/A |

Children | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 |

Rent (p.w.) | £0 | £150 | £150 | £0 |

Furlough + Universal Credit + Jobseeker’s Allowance |

| |||

With furlough scheme (p.a.) | £16,000 | £26,944 | £16,000 | £30,000 |

Without furlough scheme (p.a.) | £3,885 | £17,898 | £3,885 for 6 months, then £0 | £3,885 |

Notes: ‘With furlough scheme’ shows the furlough plus UC entitlement assuming that the employee is furloughed. ‘Without furlough scheme’ shows UC and New Style Jobseeker’s Allowance entitlement assuming that the employee loses their job and has paid enough National Insurance contributions in the past to qualify for New Style Jobseeker’s Allowance. The family is assumed to have no income other than earnings, no assets, no disabilities, and no childcare costs. Some of these individuals will be eligible for other support, such as Child Benefit or Council Tax Support. Calculations assume that the £20 per week uplift to UC has ended. Gross furlough payments are shown, though these payments are subject to tax.

Source: Authors’ calculations using TAXBEN, the IFS tax and benefit microsimulation model.

So, broadly, there are two types of furloughed employees who are going to see big drops in the amount of support that they get from the government if they become unemployed. The first are those who, whatever their previous earnings, have a relatively high earning spouse or significant level of savings, meaning they will qualify for little to no UC. The second type are middle or higher earning individuals. Under CJRS they got more support (in cash terms) than furloughed lower earners. But under UC, their (previous) higher levels of earnings do not make them eligible for any extra support.

To a large extent, this reflects a political choice implicit in the design of the welfare system to focus support on those who are on the very lowest family incomes, rather than to those who have seen a significant fall in individual earnings following job loss. In fact, by international standards, the UK is fairly unusual in this regard. A large majority of other developed countries provide some form of ‘social insurance’ scheme which offers more support for at least a few months to higher earners when they lose their job. In fact, the share of previous earnings covered by benefits for middle earners who fall out of work is well below the OECD average. Whether the experience of the pandemic and of furlough increases demand for more government support along these lines remains an open question.