The last few days have seen free school meals in England rocket to the front of the papers, as many MPs, campaign groups and businesses have lined up behind Marcus Rashford’s proposals to extend free school meal vouchers through the school holidays until Easter next year. While the motion was defeated last week, the Labour party has promised to bring the motion again – and several Conservative MPs have already indicated that it may receive a more sympathetic hearing the second time around.

In this observation, we discuss the costs of the proposal as well as some of the potential benefits it could have.

What is on the table?

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, free school meals during term-time were available to school children in low-income families. This benefit was worth around £440 per child per year. As of January 2020, 1.4 million pupils – about one-in-six – were eligible for means-tested free meals, bringing the total yearly cost to around £600 million. Additionally, free meals were available to all children in Reception and Years 1 and 2.

The closure of schools for most pupils during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic meant that most of these children were no longer able to receive their meals at the school cafeteria. Instead, schools delivered food parcels or – more commonly – provided supermarket vouchers to pupils eligible for means-tested free school meals (those receiving universal infant free school meals were not eligible for this support). At £15 per week, the vouchers were worth around a third more than the £11.50 that the government spends on a week of free school meals in school.

Extending school meal vouchers through school holidays

As part of a package to support families during the pandemic – and in response to an earlier campaign by Mr Rashford – the government agreed to extend this support over the school summer holidays. However, support has not continued during October half-term, which falls this week for much of the country. Now, the opposition parties are asking for the support to be extended again to cover the Christmas holidays and February half-term. This would be worth – and therefore cost – about £45 per pupil.

Expanding school meal coverage to all families receiving working-age benefits

There is also a separate push, by Mr Rashford as well as the recently published National Food Strategy, to extend eligibility for free school meals to all families receiving means-tested benefits. Currently, families receiving universal credit must have after-tax earnings of £7,400 or less; those on working tax credit must earn £16,190 or less. This was also proposed by the Labour and Liberal Democrat parties during the 2019 General Election campaign.

How many children would benefit, and what would it cost?

Going into the pandemic, there were over 1.4 million pupils eligible for means-tested free school meals. But the enormous economic disruption associated with COVID has seen record numbers of families moving on to universal credit. This pushes up the number of children eligible for free school meals, and so raises the cost of any extension.

Based on data collected by Understanding Society at the end of April, we estimate that the number of children eligible for means-tested free school meals had risen to almost a quarter – 1.9 million children in primary and secondary school – by the end of April. If eligibility were extended to all families on universal credit, regardless of their income, this could rise to around 2.9 million pupils.

Table 1 summarises the costs of some of the options for means-tested free school meals in England. Including the pupils who have become eligible since January, extending holiday school meals through both the Christmas holiday and the February half-term would cost around £85 million. This is a modest amount of money relative to the direct cost of the package of measures announced in response to the pandemic (less than 0.05%). It would however be about one-seventh of the annual pre-pandemic budget for spending on free school meals.

Therefore, the costs of the policy would add up if it is made permanent (or if repeated extensions mean that it effectively becomes permanent). A full year of vouchers outside of term-time would be worth – and therefore cost – around £200 per child. Even if the economy improves so that the number of people on benefits falls back to its pre-COVID level, across England it would cost around £270 million a year – nearly half as much again as the pre-pandemic budget for free school meals for those from low-income families – if these meals were to be provided through all the school holidays.

Extending free school meals to all children whose families are on working-age benefits would add considerably to the costs. In a pre-pandemic economy this would have roughly doubled the share of children eligible for free school meals, costing £380 million a year (after accounting for students in Reception through Year 2 who were already receiving free meals through the universal programme); if it were combined with support through the school holidays as well, the total cost of providing free school meals for these children would rise to £550 million.

Table 1: Estimated cost of extensions to means-tested free school meals in England

| Annual cost of term-time FSM | Extending holiday meals until Easter | Annual cost of holiday meals |

Current eligibility rules | |||

Pupils eligible in Jan 2020 | £600 million | £60 million | £270 million |

+ Pupils newly eligible (between January and end-April) | + £230 million | + £25 million | + £100 million |

Total cost this year | £830 million | £85 million | £370 million |

| |||

Extra costs of lifting the income caps (accounting for UIFSM) | |||

As at January 2020 | £380 million | £40 million | £170 million |

As at April 2020 | £350 million | £35 million | £160 million |

Note: Costs are expressed in current prices. Pupils newly eligible since January reflects the rise in the number of families receiving universal credit. Pupils who would become eligible if income caps were removed assumes that all families receiving any UC or WTC become eligible for FSM, and does not include costs for pupils in Reception-Year 2 (who are already benefitting through Universal Infant Free School Meals). Calculated for pupils in primary and secondary school (not nursery). All costs exclude Barnett consequentials, which add around 19% to the cost of each policy if not funded via higher taxes or other spending cuts in areas that are devolved.

What impacts might this policy have?

The discussion so far has focused on the impact that free school meal support can have for families struggling to make ends meet, especially during the pandemic. It is certainly true that means-tested free school meals reach some of the poorest people in the country, and many have been struggling with food insecurity during the pandemic.

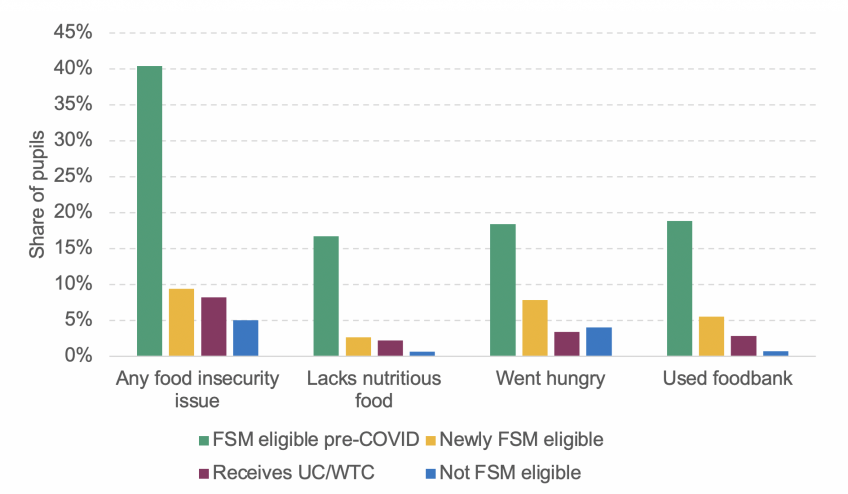

Figure 1 shows the share of children living in families that had some markers of food insecurity during the pandemic. Among the one-in-six children who were eligible for free school meals before the pandemic, 40% lived in families who reported a lack of nutritious food during lockdown or family members going hungry in the previous week, or used a foodbank in the previous month. During the lockdown around 80% of these children received vouchers from their school, which suggests that – at least during that part of the national lockdown – the vouchers were only an imperfect support for these families. This likely reflects the financial difficulties that some of these families were in, but difficulties in accessing supermarkets during the lockdown might also have played a role.

By contrast, children who became eligible for free school meals during the pandemic were far less likely to live in food-insecure households in April. This could be because the shock to households’ finances was still, at that point, relatively recent; even families who had qualified for benefits might have been able to use savings, loans, or support from others to help tide themselves over.

Families that are eligible for working-age benefits but have incomes above the free school meals cap also look much less food insecure than those who were eligible for free meals back in January. This likely reflects the direct impact that the income cap has on targeting resources to the poorest families even among a group that is itself among the poorest in society.

Figure 1: Share of pupils in families experiencing food insecurity, end-April 2020

Note: ‘Any food insecurity issue’ captures pupils whose parents report any of the three other food insecurity indicators. Food insecurity questions are asked about the family as a whole, not necessarily the child.

Source: Understanding Society COVID module, wave 1.

There may also be broader benefits to supporting nutrition among disadvantaged children. Previous IFS research has found that universal infant free school meals boosted attainment, at least in disadvantaged local authorities. Researchers at the University of Essex find that, once the policy was fully rolled out, it helped young children to maintain a healthier body weight. The researchers also found some evidence that the benefits from free school meals slipped during the school holidays. On the other hand, some of these benefits are likely due to standards for healthy school meals, which will not be under the direct control of government or schools when holiday-time vouchers are provided.

Conclusion

The push to extend free school meals through the holidays has seen broad support among a wide cross-section of society. The option that is currently being discussed – extending this support through the Christmas and February half-term holidays – would add only a small amount to the total bill for COVID-19 support, and would target children in families that are suffering high rates of food insecurity.

But after the current debate on this specific question, there will almost certainly be wider discussions about the future of free school meals support. Making this benefit permanent would cost £270 million in the longer run (assuming benefits caseloads return to their pre-pandemic level). That would be a substantial extension to spending on free school meals, though it could also have some wider benefits for children’s health and attainment. But any debate on whether this should be done will hinge on whether the COVID-19 pandemic has put exceptional stress on the budgets of the very poor families who are eligible for free school meals – or whether it has simply laid bare the challenges that families on very low incomes will continue to face even in more normal times.