One group which is going to find the next months and years especially difficult are those entering the labour market this year. Experience from previous recessions tells us that graduates will be less likely to find work and will start off in lower-paying occupations than they might have expected. Given the likely scale of the downturn into which they will be graduating it is likely to take at least five, and perhaps ten, years for these effects to wear off. This, alongside the loss of some face-to-face teaching, has led some students to request a rebate on their fees. That does not look like a good way of responding to a weak labour market. The nature of the income-contingent loan system is precisely to insure graduates against bad outcomes. If they earn less they will pay back less. What they need above all else is a sharp economic recovery. Without that they are likely to suffer lower incomes for many years to come.

Main article

We are now in the midst of a huge economic downturn. The economy could shrink by between a quarter and a third over the second quarter of this year. This is affecting millions of people who are being furloughed, losing incomes, or losing their jobs entirely.

The effects are not being felt equally across the population. We have already shown that those on low earnings are much more likely to work in sectors affected by the shutdown than are higher earners. It is also the case that workers under the age of 25 are two and half times as likely as those over age 25 to work in sectors that have been closed down.

So the young who are already in the labour market are suffering and suffering more than older workers. But one group may end up suffering even more, and that is the group of young people looking to enter the labour market for the first time this year. This is a worrying time for students. And it will be a worry not just for this year but for their future job and earnings prospects.

We know from previous experience that entering the labour market during a recession can have a negative effect on earnings for years afterwards. Previous IFS work used data on the earnings and employment of young people who left school or university during the last three recessions and compared them to what happened to the earnings and employment of similar young people entering the labour market in normal times. On average unemployment rates rose by four percentage points during those recessions. That led to a probability of being in paid work that was 7 percentage points lower for young people a year after they entered the labour market. Even five years on they were still slightly less likely to be in work at all than were young people who graduated or left school in happier times. Earnings were also affected. For those who did find a job they were 6% lower after one year than they were for ‘normal’ cohorts and still 2% lower after five years – though this effect was definitely more pronounced for school leavers than for graduates.

There is particularly robust evidence of a long-term negative effect on graduate earnings from entering the labour market in a recession in the US, with persistent earnings reductions lasting ten years for unlucky graduates. Researchers also find that graduating in a recession is associated with starting work for lower paying employers. Clarke also finds that in the UK, there is a particular impact on the probability that graduates will start in, and for some years remain in, low paid ‘non-graduate’ work in sales, customer service and leisure for example. He finds that those who graduated after the 2008 recession had 30% higher chance of working in one of these occupations a year after graduating and that probability remained elevated seven years later.

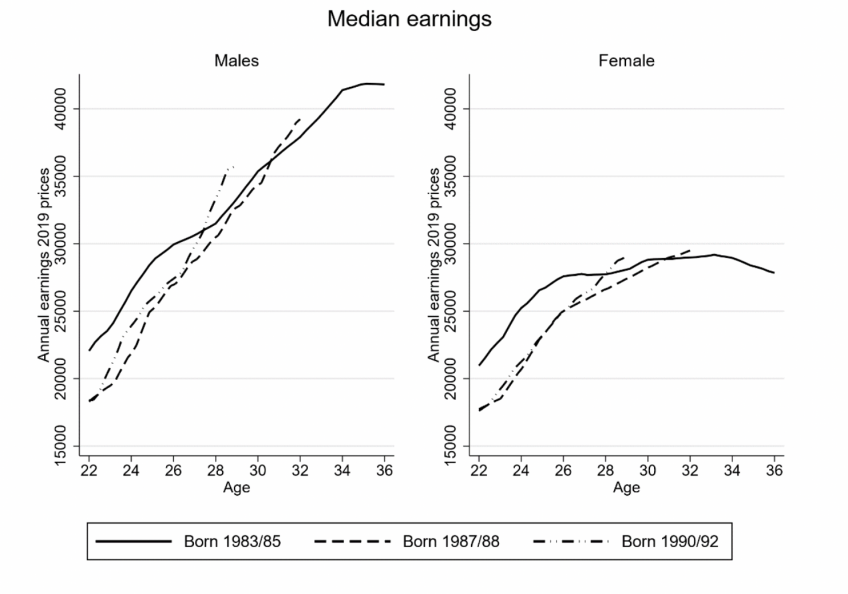

New analysis of the Labour Force Survey illustrates the effect. The chart shows the evolution of the earnings of three groups of male and female graduates. The first - born between 1983 and 1985 - would have graduated before the 2008-09 recession. The second - born in 1987 and 1988 - would have graduated during the recession, while the third - born between 1990 and 1992 - graduated later.

One would usually expect those born later to earn more at any given age as earnings gradually rise across the economy. It is very striking then that the earnings of that middle cohort which graduated into the recession started off well below those of the first cohort and their earnings did not catch up until they had reached their early 30s. The later cohort, as you’d expect, earned more than the group graduating into the recession at all ages, though even they didn’t overtake the earnings of the oldest group until they had reached their late 20s. The effects of the 2008-09 recession were long-lasting in the sense that the economy continued to do poorly for a long period, depressing the wages of graduates for that whole period of poor performance.

Figure 1: Earnings by age for three cohorts of graduates entering the labour market before, during and after the 2008-09 recession

Source: LFS

This is all in the context of a very poor period for the earnings of young graduates. IFS analysis of graduate earnings over time shows that the median earnings of graduates in their late 20s fell by nearly 20% between 2008 and 2013 and was only just starting to recover by 2016. At this point they were still at roughly the same real-terms level that they had been at 20 years earlier, in the mid-1990s. It is important to take some care with these longer-term comparisons, though, as the increasing number of graduates means that the composition is changing – more of the more recent graduates will have entered higher education with lower attainment levels.

Even against this background, those graduating this year can expect to find it harder to find employment and, especially, harder to find well-paid employment than did their immediate predecessors. Especially if the economy takes a long time to return to trend, they can expect to earn less than they might have expected for a considerable period of time. Exactly how that will pan out is quite uncertain. The labour market at the point of graduation is likely to be substantially more difficult than back in 2008-09, suggesting a bigger hit to employment prospects and earnings. The speed of the recovery is unknown though and the longer-term experience of this cohort of graduates will depend on the speed of that recovery.

Even so, waiving or reducing tuition fees would not tackle the issues faced by new graduates despite some calls to do so. That may or may not be an appropriate response to a loss of a term’s face to face teaching, but it does not look like an appropriate response to graduating into a difficult labour market.

Indeed, it is a strength of the current funding system based on income contingent loans that if the graduates’ incomes are lower then their loan repayments will be lower. As we have argued before, because the vast majority of students will not fully pay off their loans within the allotted 30 years, any reduction in fees or any fee waiver can only benefit the fifth or so of graduates who go on to earn the most. It would be of no value to those who end up doing badly in the labour market. That is in the nature of a system of income contingent loans; they already effectively provide insurance against the sort of difficult labour market situation which new graduates are likely to endure. Their earnings will be lower and so, therefore, will their repayments.