Note: After this piece was finalised, the Labour party announced plans to make its free school meals offer more generous, offering free school meals to all secondary school pupils whose families receive universal credit. With this addition, they would offer free meals to the same group of students as the Liberal Democrats; the costings for Labour’s new offer are therefore the same as the costings for the Liberal Democrats.

The commitment on free school meals for secondary school students was not included in the Labour party’s manifesto, and so the extra spending it implies was not explicitly included in the manifesto costing of the 'Free School Meals' policy. This money would need to be found either from within the party's plans for increased school spending (implying that around £0.3 billion (in today’s prices) of the overall £7.5-billion real-terms increase in schools spending would be used up by this extension to free school meals), or outside of the manifesto budget (through additional tax rises, spending cuts in other areas, or an increase in borrowing).

In their manifestos, both the Labour party and the Liberal Democrats have promised to extend free school meals to more children. The Labour party would introduce free school meals for all children in primary schools, while the Liberal Democrats would offer them to all secondary-school pupils whose families are receiving universal credit as well. Meanwhile, in their manifesto the Conservative party promises to “maintain our commitment” to free school meals – which we interpret as a plan to keep policy as it is.

We estimate that both parties’ costings of their respective policies are plausible, though the eventual bill will depend on whether they choose to stick to current policy and freeze per-meal spending in cash terms, or to offer real-terms protection in the amount of funding per lunch. Of course, both parties are promising to take a benefit that is currently means-tested and extend it to all primary school children; by definition, this will tend to help those in better-off families. And, while families would welcome the time and money savings from having school lunches provided for free, it’s not yet clear that this policy would have big additional benefits for children’s health or attainment in school.

What is the current free school meals policy?

As it stands, about 15% of pupils receive means-tested free school meals. The eligibility criteria are somewhat complex (see full rules here), but broadly these free meals are targeted at the lowest-income families. In addition to these means-tested free school meals, all children in state schools in Reception through Year 2 – regardless of their family income – have been eligible for universal infant free school meals since 2014. In total, around 2.8 million students from Reception to Year 11 get a free lunch at school.

The government currently gives schools £2.30 per school meal, which has been frozen in cash terms since universal infant free school meals were introduced. This has put additional pressure on schools delivering the meals, since the cost of delivering these meals – for example, in food and staffing – will have risen. If it wanted to reverse these real-terms cuts to per-meal spending and protect funding going forward, the government would have to increase the funding rate to £2.51 per meal this year.

Other than the funding rate, two of the biggest drivers of the cost of school meals policies are the number of pupils and the take-up rate. We use data from the Department for Education on current pupil numbers, coupled with population projections from the ONS, to predict the number of students in 2024. We assume that the take-up rates of the new, universal entitlement are 87% – the same as the take-up of the current universal offer.

How much would Labour and the Liberal Democrats’ plans cost?

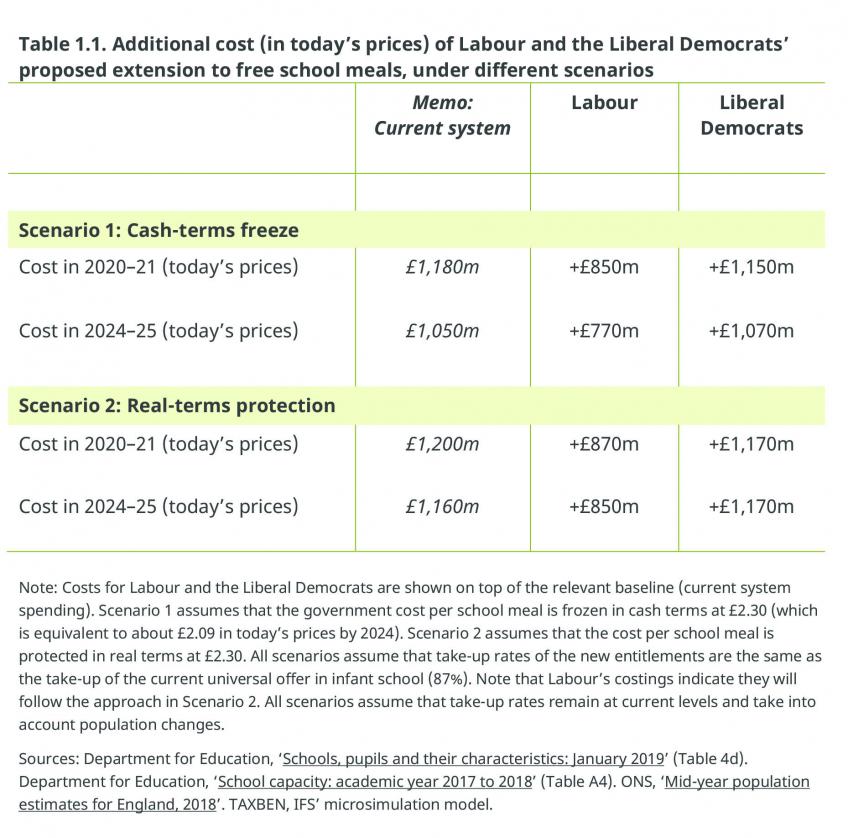

The Labour party has suggested that it would protect per-meal funding in real terms going forwards, but the Liberal Democrats have not been clear about the school meal funding rate they would set. Table 1 therefore summarises the cost of both parties’ policies in today’s prices, both for next year and for the end of a five-year parliament in 2024, under two different scenarios. The first assumes that the rate per meal continues to be frozen in cash terms at £2.30; this would leave spending per meal at £2.09 in today’s prices by 2024. The second scenario assumes real-terms protection at £2.30 going forward; this is the approach that Labour has said it would take.

Labour

We find that Labour’s manifesto plans for free school meals could cost around £850m in 2024 (in today’s prices), assuming the party protects spending per meal in real terms going forward. The party costs its promise at £900 million in 2023 (£830 million in today’s prices), which is essentially the same as our costing.

Liberal Democrats

Under the current system, families receiving universal credit will only be eligible for free school meals if they have net earnings (after tax and before benefits) below £7,400 a year. The current system is available for families with gross income (before tax and benefits) of up to £16,190. IFS research has shown that, while the change to universal credit will have big impacts on who is entitled to free school meals, it will have only a small effect on how many children are eligible.

Under the Liberal Democrats’ proposals, all secondary-school students whose families are receiving universal credit would be eligible for free school meals, regardless of their earnings. Based on IFS’ microsimulation model of the tax and benefit system, once universal credit is fully rolled out around 40% of secondary school students would be eligible for free school meals under this policy – two-and-a-half times as many secondary students as are eligible under current policy.

This would extend eligibility to around 820,000 students in secondary school (Years 7 through 11) in 2024, at a cost of between £280 million and £310 million depending on the funding rate. Coupled with the cost of universal primary free school meals, the Liberal Democrats’ promise could cost between £1.1 billion and £1.2 billion.

The party costs this promise at £1,160 million in 2024 (£1,050 million in today’s prices). This is the same as the cost we estimate in Table 1 for their plans, assuming a cash-terms freeze in per-meal funding; this means that the party appears to have budgeted enough to deliver on this commitment. Of course, if the Liberal Democrats wish to offer real-terms protection in per-meal spending, they might need to find an extra £100 million or so by 2024. And, as with all programmes, actual costs will vary from year to year with population size and take-up rates.

Conclusion

Both Labour and the Liberal Democrats are promising a more generous offer on free school meals, and both parties seem to have budgeted enough to deliver on their commitments. Under Labour’s plans, spending per meal would rise in line with inflation, while the Liberal Democrats’ costings suggest they might continue the current policy of keeping spending frozen in cash terms.

Although this is far from the biggest budget line in an election that has so far been characterised by big spending increases in both the Labour and Liberal Democrat manifestos, these costs are not trivial. And it’s important to remember that making a policy currently targeted at the poorest 15% of children universal will, by definition, mainly benefit the better-off 85%. Of course, many of these families will also be hard-pressed, but it’s not clear that offering free meals to students from comfortably-off families is the most efficient or cost-effective way to “poverty-proof” schools.

Previous IFS research has shown that, at least in infant schools, universal free school meals deliver some benefits for attainment; in a pilot, Year 6 students in two disadvantaged local authorities made an additional two months’ progress over the course of two years. However, the pilot wasn’t able to pinpoint how these changes came about: the pilot found no benefits in terms of children’s behaviour or focus, their attendance at school, their weight or the amount of junk food they ate over the day. And while a subsequent evaluation of the universal infant free school meals programme found that some parents and school leaders believed the programme had benefits for education or health, the authors did not test these effects statistically.

Without understanding what’s driving any academic benefits, it’s hard to be confident that they will persist if universal meals for all primary pupils are rolled out nationally. So while it’s certain that making school lunches free for all primary school children – or more secondary school students – would save families time and money, it’s not yet clear whether these policies would have big further benefits for children’s attainment or health.