We are now down to the final two Conservative Party leadership contenders: Rishi Sunak and Liz Truss. On 5 September we will know which of the two is the next Conservative Party leader - and therefore Prime Minister - so their visions for tax and spending matter. Below we provide some initial analysis of the plans that have been set out so far.

Permanent changes to personal taxes: reversing the NICs rise

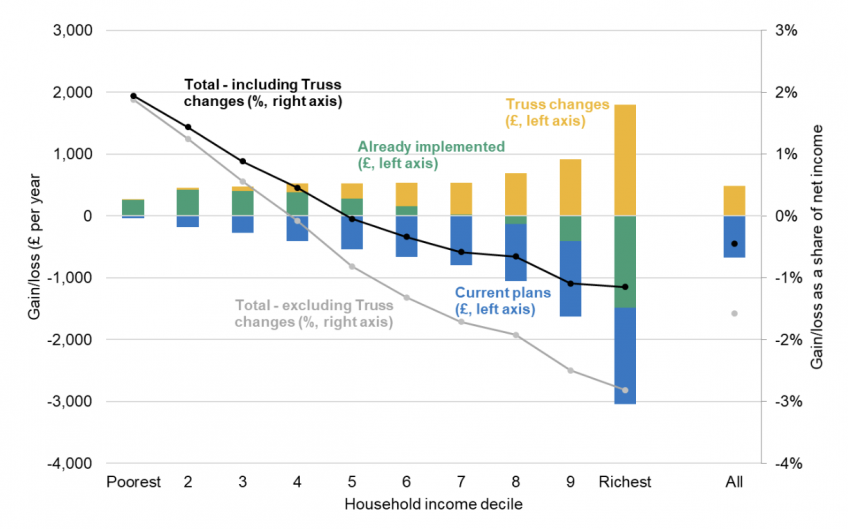

The government has already made a number of permanent changes to personal taxes since the beginning of the Parliament - both tax rises and tax cuts - and on current plans will make several more. So far, the government has raised tax by increasing National Insurance contributions (NICs) and at times freezing income tax thresholds, and cut tax by raising the threshold at which workers begin to pay NICs. It has also cut duties on alcohol and fuel, and has implemented some increases to benefits. Looking forward, under current plans income tax and NICs thresholds will be frozen for a further three years (a tax rise), and the basic rate of income tax will be reduced by one penny in the pound in 2024-25. Figure 1 shows the impact of these reforms once they are fully in place. Those implemented so far are broadly progressive, with the benefit increases boosting incomes among poorer households and the tax rises taking from richer ones. The plans over the next few years are also progressive, though amount to a takeaway across the board - the high-inflation environment means that the freezing of income tax and NICs thresholds is a much bigger tax rise than originally intended.

Mr Sunak has not announced any specific intention to deviate from these plans. Ms Truss, however, has stated that she would reverse the increase in NICs rates, at a cost of £13 billion per year. This boosts incomes across the board, but does so most for higher-income households who have the most income from employment. Nonetheless, taken in the round, the package of policies implemented across the parliament as a whole would remain highly progressive (see the black line).

Figure 1. Impact of permanent changes to the tax and benefit system

Note: ‘Already implemented’ and ‘current plans’ bars include freezes to income tax thresholds, the rise then freeze to the NICs primary threshold, cut to the basic rate of income tax, cut to the universal credit taper rate and increase in work allowances, increases in local housing allowance rates, freezes to fuel and alcohol duties, and the introduction of the health and social care levy. The ‘Truss changes’ bar includes the removal of the health and social care levy.

Source: IFS analysis using the IFS tax and benefit microsimulation model, TAXBEN, run on uprated data from the Family Resources Survey and the Living Costs and Food Survey.

Ms Truss has motivated the reversal of the NICs rise as a means to boost economic growth. Certainly it would strengthen incentives to enter work and to earn more, though these effects would not be nearly sufficient to make the reform pay for itself.

Ms Truss has also indicated an interest in further tax cuts, notably promising to ‘review taxation of families to ensure people aren't penalised for taking time out to care for children/elderly relatives’ - perhaps by making the income tax personal allowance (rather than just 10% of it, as now) transferable between members of couples - but has not made definite, specific commitments on them.

Mr Sunak says he would also cut taxes, but only once inflation has been brought under control - a matter of ‘when, not if’, he claims.

Additional temporary support: a moratorium on green energy levies

Alongside these permanent changes to the tax and benefit system, the government has so far put in place two main kinds of temporary support to help households with the rising cost of living.

First, a set of one-off grants for households worth about £24bn in total – with something for everyone, but more generous support targeted at older people and those on means-tested benefits or disability benefits. The government has also provided about £1bn for councils to provide additional discretionary support to those in need.

Second, a one-year 5p per litre cut in the rate of fuel duties, reducing them from 58p to 53p per litre at a cost of £2.5bn. The government’s public finance forecasts currently assume that the temporary 5p cut will be reversed next April and that fuel duties will rise with RPI inflation on top of that. Over the past decade or so, Conservative Chancellors have shied away from increasing fuel duties even in line with low inflation rates, let alone high inflation rates plus an additional 5p per litre. However, if either candidate wishes to cancel the increase, they would need to find additional money to pay for it.

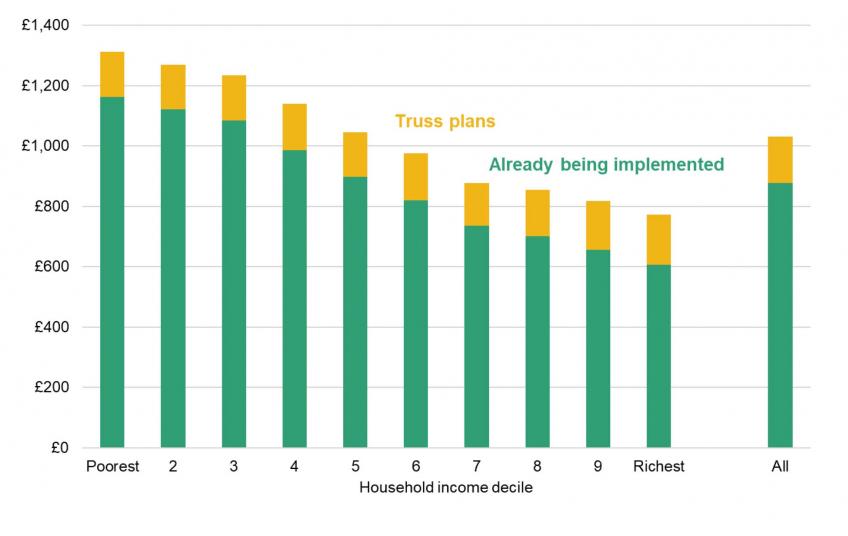

To provide further immediate support, Ms Truss has said she would have a ‘temporary moratorium on the green energy levy’. According to Ofgem, as of 1 April 2022, a combination of various levies increased energy bills for a household with typical energy consumption by £153 per year – though that figure will change over time (the levies fall automatically when wholesale electricity prices rise, and vice versa) as well as varying with household energy consumption.

To the best of our knowledge, Ms Truss has not specified when the temporary moratorium would begin and end, exactly which levies on energy bills would be suspended (such as whether it would include the climate change levy on businesses’ energy use as well as the various levies that apply to households too), and what would happen to the subsidies for renewable energy generation that some of the levies fund. These details would be crucial for assessing the likely effects of the policy; and without them, it is impossible to say how much it would cost.

The chart below assumes that the moratorium reduces average annual bills by £153, ignoring any other effects, and shows the average gain for households in different income groups (reflecting differences in energy consumption) per year the moratorium is in place.

Figure 2. Gains from temporary measures to support households

Source: IFS analysis using data from Ofgem and the IFS tax and benefit microsimulation model, TAXBEN, run on uprated data from the Family Resources Survey and the Living Costs and Food Survey.

But the effect of cutting green levies is more complicated than it might seem because of the way the levies interact with the UK’s emissions trading system (ETS). This sells a fixed number of permits to emit a tonne of CO2 to firms covered by the scheme, with the number of permits falling each year. Reducing energy levies would increase emissions from the power sector; unless the government increased the total number of ETS permits (despite Ms Truss’ commitment to the existing ‘net zero’ targets) this would push up the cost of ETS permits for other sectors in the scheme and encourage firms to bring forward their use of ETS permits from future years. This would have paradoxical effects: offsetting some of revenue losses through higher ETS auction revenues, raising the cost of other activities covered by the ETS (such as flights and some industrial processes), raising energy costs for households once the moratorium is over (or if it were made permanent), and having no net effect on total UK emissions from ETS-covered sectors.

Business taxation: cancelling the corporation tax rise

The March 2021 Budget announced an increase in the main rate of corporation tax, from 19% to 25%, from April 2023 for big companies (those making annual profits in excess of £250,000). Mr Sunak proposes to go ahead with that increase; Ms Truss proposes to cancel it.

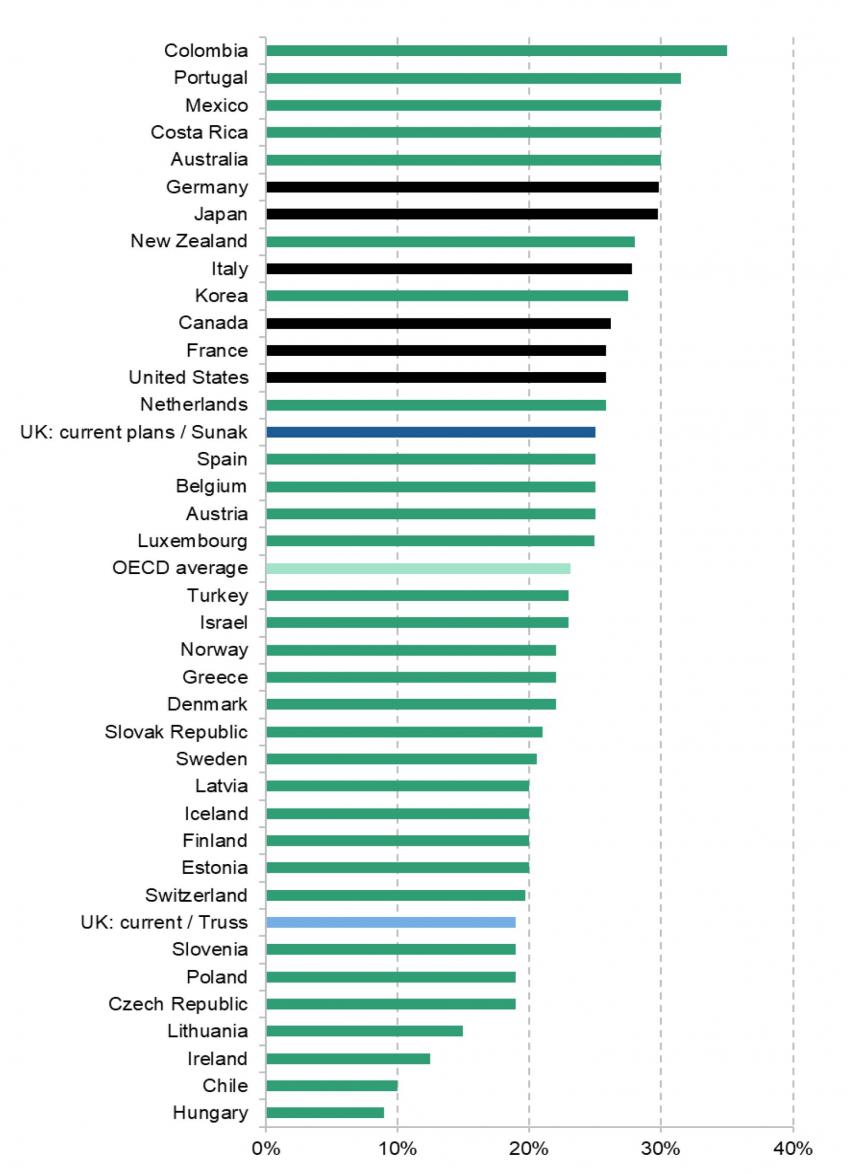

Figure 3. Headline corporate income tax rates, 2022

Note: Includes sub-national taxes. G7 countries shaded black.

Source: OECD.

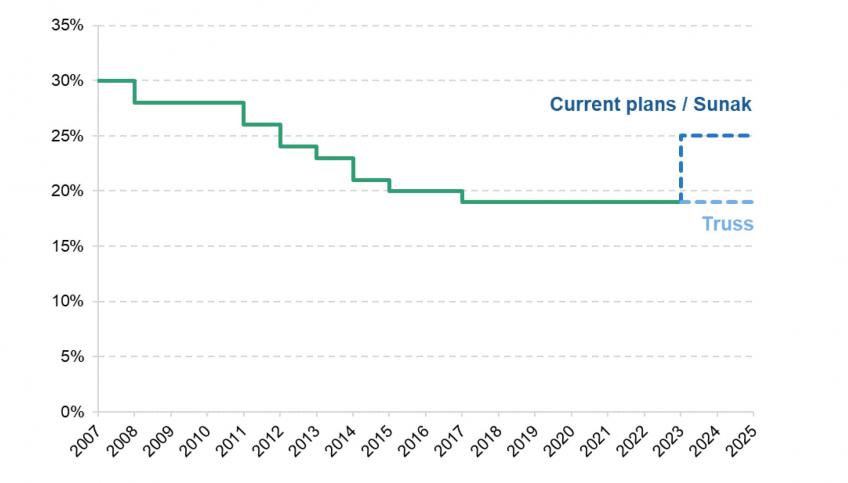

Figure 4. The main rate of UK corporation tax

Note: The horizontal axis has April of each year marked.

Source: IFS Fiscal Facts.

As Figure 3 shows, the UK currently has one of the lowest headline rates of corporation tax in the developed world. Increasing it to 25% would leave the UK’s rate slightly above the OECD average, though still the lowest in the G7 (once sub-national taxes are taken into account). The rate would still be lower than it was before 2012 (see Figure 4).

Cancelling the increase would cost £17bn a year, according to government estimates. However, this estimate doesn’t allow for corporation tax to affect investment. As Ms Truss points out, a lower tax rate would strengthen incentives to invest in the UK and thereby promote economic growth, helping to recoup some of the initial cost of the tax cut. We would therefore expect the long-run cost to be considerably lower than £17bn a year – though the effect would certainly not be big enough for the tax cut to pay for itself.

Mr Sunak takes a different approach. He argues that cuts in the headline rate of corporation tax have had only a limited effect on investment, and that it would be more effective to target incentives for investment more directly. The UK’s tax allowances for investment are ungenerous by international standards, meaning that the UK’s overall corporation tax regime is less competitive than the low headline rate suggests. Accordingly, in May the Treasury published a policy paper inviting views on a range of possible ways to increase investment allowances, and Mr Sunak (while still Chancellor) indicated that he intended to announce some such increase in the autumn Budget, to take effect next April (when the temporary ‘super-deduction’ for investment currently in place expires and the headline rate rise takes effect). Of course, it would be open to Ms Truss to introduce such increases in investment allowances even while cancelling the headline rate rise.

Public spending

The candidates have been less forthcoming about their intentions for public spending.

As things stand, unexpectedly high inflation is already set to lead to another dose of austerity for public services. The government’s existing departmental spending plans were set out by Rishi Sunak at the spending review last October. At that time the expectation was that inflation would peak at around 4 per cent. It is now set to peak at 11 per cent and stay higher for longer. Those plans were also built on an assumption of pay awards between 2 and 3 per cent per year; public sector workers have now been offered pay increases averaging around 5 per cent.

Whoever is in office in the autumn will have to make a choice between topping up spending plans to shore up public services, or requiring any additional costs to be met from within existing budgets. The former would eat into the fiscal headroom available for tax cuts; the latter would mean a deterioration in the quality of public service provision. Liz Truss has promised to hold a new spending review, but it is possible that such an exercise could lead to lower, rather than higher, departmental budgets. She is, after all, promising more than £30bn per year of tax cuts.

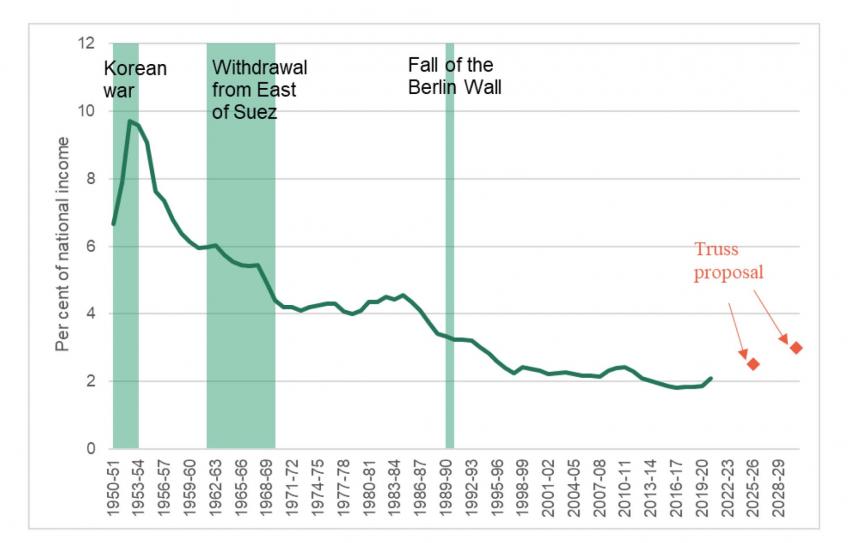

Defence

One area where candidates have provided more clarity is on defence spending. Liz Truss has promised to increase the defence budget from its current level of around 2.1% of GDP to 2.5% of GDP by 2026, and 3% by 2030. An extra 0.9% of GDP is equivalent to around £23 billion in today’s terms.

The Ministry of Defence budget has already been fixed for the remainder of this parliament as part of the 2021 Spending Review. If budgets between now and 2024-25 are left as they are, reaching 2.5% of GDP by 2026-27 would require two years of 17% real-terms budget increases (i.e. 17% increases over and above inflation) after that point. (Alternatively, if spending settlements were reopened, meeting this target would require 7% annual real increases between 2022-23 and 2026-27).

To then reach 3% of GDP by 2030-31 would require a further four years of 6% real-terms budget increases. This would represent a substantial, sustained budget commitment that would take defence spending as a fraction of national income to its highest level since 1994. It would also limit the amount available for other public services.

Rishi Sunak has not indicated any firm ambitions for defence spending, other than that the UK would continue to meet the NATO target of spending at least 2% of GDP.

Figure 5. Defence spending over time

Notes: Calendar year data used from 1950 to 1954.

Sources: Office for Budget Responsibility, Fiscal Risks and Sustainability Report (July 2022), based on calculations by Bank of England, HMT, IFS, OBR

Public finances

The government is currently committed to having public sector net debt falling as a fraction of national income by 2024-25, and to balance the current budget (i.e. to cover all day-to-day spending out of tax revenue, borrowing only to invest) by the same year. In its March 2022 Economic and Fiscal Outlook, the Office for Budget Responsibility estimated that the government was on track to meet both of these self-imposed fiscal targets with around £30 billion to spare.

This does not mean that a new Prime Minister and Chancellor would automatically have £30 billion of ‘headroom’ within those rules for tax cuts. It is a projection around which there is a huge amount of uncertainty. The economic outlook, and in particular the outlook for inflation, has materially changed since March. Higher inflation acts to push up tax revenues, particularly when the government has chosen to freeze various tax thresholds in cash terms. But to focus just on the tax take ignores the other side of the ledger. Higher inflation means higher spending on various inflation-linked benefits and pensions, higher spending on debt interest payments, and pressure for higher spending on public services. Much of the government’s substantial cost-of-living support package is intended to be temporary, as described above, and if that were indeed the case it would not significantly affect ‘headroom’ against the fiscal targets, which constrain borrowing in the medium term. However, there will undoubtedly be calls to extend at least some of the support, such as the cut to fuel duty, when the time for its supposed reversal comes.

Liz Truss’ package of tax cuts would cost more than £30bn - possibly considerably more, depending on how exactly she proposes to cut green levies and on the costs of other policies that she proposes to examine or that have not been spelt out fully. Without counteracting measures this would likely result in the current fiscal rules being broken, with day-to-day spending still exceeding tax revenues at the end of this parliament and with national debt still rising as a proportion of national income.

This suggests that Ms Truss would be likely either to make cuts to overall spending plans or to change the fiscal rules. She has indeed committed to a Spending Review, though without an explicit intention to change overall spending in any particular direction, and with the only specific spending pledge so far being a £23bn increase in defence spending by the end of the decade. She has also hinted that she may change fiscal rules. This may resolve the arithmetic for now in a narrow sense, but in the end lower taxes do mean lower spending, whatever self-imposed fiscal rules may allow in the short term. As things stand, then, we certainly have a sense of broad direction on tax, but a much vaguer sense of her overall approach to the balance of tax, spend and stewardship of the public finances.

Ms Truss has also indicated that she would like to see government debt put ‘on a longer-term footing’. This seems to refer to locking in long-term interest rates and increasing the average maturity of government debt, if such longer-term debt could be easily placed. Notably, according to the OECD’s Sovereign Borrowing outlook, the UK’s debt already has a longer maturity than any other OECD country, and nearly twice as long as the weighted average across the 38 countries. There would be arguments for further increasing that maturity, but it would not ‘pay for’ the tax cuts. Ultimately, however government debt is structured and whatever borrowing the fiscal rules allow in the short run, lower taxes can only be paid for in the long run by lower public spending than we would otherwise see. And while tax cuts can promote economic growth, none of the tax cuts proposed by any of the candidates during the Conservative leadership contest would do this enough to pay for themselves.

To the extent that tax cuts were indeed financed by additional government borrowing, rather than spending reductions, they would inject additional demand into the economy and further increase inflationary pressures. It is difficult, though, to say by how much, and this would vary depending on the specific package of tax cuts. Such a fiscal loosening might be met by a tightening of monetary policy, i.e. the Bank of England increasing interest rates further and/or more quickly than they otherwise would. Were that to happen, the net effect would involve some redistribution away from those exposed to interest rate rises to those benefiting from the package of tax cuts.

Conclusion

When it comes to tax and spend, Rishi Sunak is proposing nothing beyond current government policy in the short term - unsurprisingly, given that he set these policies as Chancellor. We therefore know a lot about what we would get under his premiership, at least initially, without his having to say much. We would have tax heading towards its highest sustained level in 70 years as a share of national income, though with an intention to bring taxes down once he has ‘gripped inflation’. Public service spending would be rising over the remainder of the parliament, though at a considerably less generous pace than originally intended due to higher inflation, and with almost all departmental budgets still considerably down in real terms on their 2010 level. There would be some headroom against the government's fiscal targets - including the target of taxes covering all day-to-day spending by 2024-25 - though not enough to allow the Chancellor to rest easy, given the degree of economic turbulence and uncertainty. In the longer term, Mr Sunak has been clear that he does wish to cut taxes, but not until inflation has fallen back.

Liz Truss is proposing something quite different from Mr Sunak, with tax cuts worth more than £30bn per year - and possibly considerably more - relative to current plans. This certainly represents a genuine choice for those who will elect the next prime minister. But those pledges will have implications beyond the tax system, and these remain unclear. They will mean higher borrowing or less public spending, or some combination. Without spending reductions, the tax promises would likely lead to the current fiscal rules being broken, and Ms Truss has hinted that the fiscal rules may change. In this context it is always important to remember that, whatever a chosen set of self-imposed fiscal rules might allow in the short term, in the end lower taxes do mean lower spending. A fresh Spending Review has indeed been promised, but without clarity on whether current plans will be adjusted up or down – apart from on defence, where Ms Truss has promised a £23bn budget increase by the end of the decade.

As the person who set the current plans as Chancellor and who wishes to stick to them, Mr Sunak’s approach to the overall balance of tax and spend and the stewardship of the public finances is set out by default, at least in the near future. Ms Truss does not have that luxury because she favours substantial tax cuts, and the implications of these for spending and the public finances are yet to be fleshed out. As the two-horse race ensues the contest would benefit from having a clearer idea of how their broad approaches to spending and management of the public finances, as well as tax, compare.