Paul Johnson, Director of IFS, said:

“We’ve learned to expect some degree of smoke and mirrors in the Budget. Today was no different, only on this occasion Mr Hunt decided to tax the smoke and to mirror the Labour party’s tax pledges on non-doms and North Sea oil. Alongside a new tax on vaping and an increase in tobacco duty, this was enough to allow Mr Hunt to announce another, well-trailed cut to National Insurance.

“This £10 billion tax cut will benefit millions of workers. Put it together with the 2p cut from November’s Autumn Statement, and those on just above average earnings will gain around £1,000 a year. Focusing tax cuts on National Insurance, rather than income tax, is to be welcomed: doing so reduces the tax wedge between different sorts of income, benefits those of working age in work, and should have marginally more positive work incentive effects. On the back of similar cuts in November, it marks a clear break with the trend of the past half-century, during which headline income tax rates have come down and National Insurance rates have, until now, inched up.

“Changing the basis of non-dom taxation to residency, rather than the out-of-date concept of domicile, is a big and welcome move. The rather bizarre method of withdrawing child benefit from high-income families is in need of reform, and the changes coming into effect in April mitigate some of the worst features of the current system.

“Some bright spots, then, though the big picture on tax remains much the same. Come the election, tax revenues will be 3.9% of national income, or around £100 billion, higher than at the time of the last election. This remains a parliament of record tax rises.

“While the OBR got a little more positive in its projections, the picture on living standards also remains dismal. On average, households will be worse off at the time of the next election than they were at the last, following nugatory real earnings growth.

“The OBR marginally increased its forecasts for economic growth, but the overall public finance picture remains largely unchanged from the autumn. The Chancellor is still on track to stabilise debt as a fraction of national income in five years’ time, just about, but only on the basis of a pie-in-the-sky promise to increase fuel duties (this time we mean it – promise!) and a set of post-election spending plans that still imply substantial cuts to funding of many public services which are clearly struggling with their current level of funding. While his ambition to improve public sector efficiency and productivity is the right one, and his injection of capital funding into the NHS is a sensible way of doing so, delivering on such plans and securing cash savings will be very tough indeed. That capital funding won’t arrive until 2025–26 in any case.

“We should at least be grateful that Mr Hunt didn’t pencil in even larger cuts to as-yet-unspecified public services. Nonetheless, actually implementing his plans would require cutting unprotected services – including councils, courts, further education colleges aand prisons – at around half the pace that George Osborne did between 2010 and 2015. Within the realms of possibility, perhaps, but there will be far less in the way of low-hanging fruit this time around, and banking on big improvements in public sector productivity is a risky business. Whoever is Chancellor at the time of the next Spending Review – which the Chancellor confirmed will not take place until after the election – might wish they’d chosen a different line of work.”

Cuts to National Insurance contributions

The further 2p cut to the main rates of employee and self-employed NICs will:

- benefit 27.6 million employees and 2.2 million self-employed workers at a cost of around £10 billion per year. Everyone earning more than £12,570 a year will benefit, with higher earners benefiting more in cash terms.

- be a tax cut worth £450 a year to an employee on average (mean) full-time earnings of £35,000. As the Chancellor said, when combined with the 2p cut in January this rises to £900 a year.

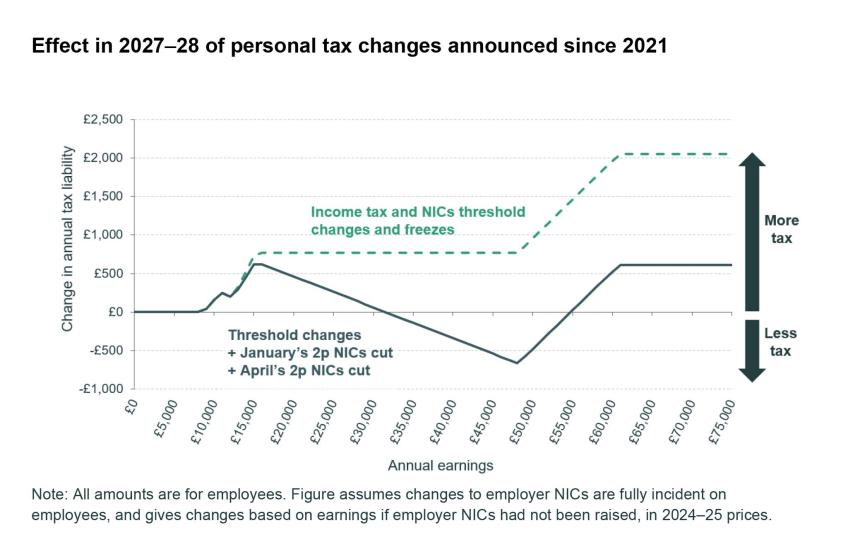

But in aggregate the NICs cuts just serve to give back a portion of the money that is being taken away through other income tax and NICs changes – in particular, multi-year freezes to tax thresholds at a time of high inflation. Overall, for every £1 given back to workers (including the self-employed) by the NICs cuts, £1.30 will have been taken away due to threshold changes between 2021 and 2024, with this rising to £1.90 in 2027.

But the pattern of gains and losses varies by earnings level:

- In 2024–25, the net effect of all NICs and income tax changes since 2021 for an average earner will be a tax cut of about £340. Overall about half of employees – the 14 million earning between about £26,000 and £60,000 per year (the 40th and 90th percentiles of the earnings distribution) – will be better off. Any other employees earning enough to pay NICs or income tax will be worse off, because the cuts to NICs rates are more than offset by other tax rises.

- By 2027–28, after another three years of real-terms cuts to tax thresholds, the net effect of income tax and NICs changes since 2021 for the average full-time earner will be a tax cut of £140 per year. Overall about a third of employees will still be better off as a result of all these changes: the 9 million earning between about £32,000 and £55,000 per year. Taxpaying employees earning less or more than that will lose.

High Income Child Benefit Charge (HICBC)

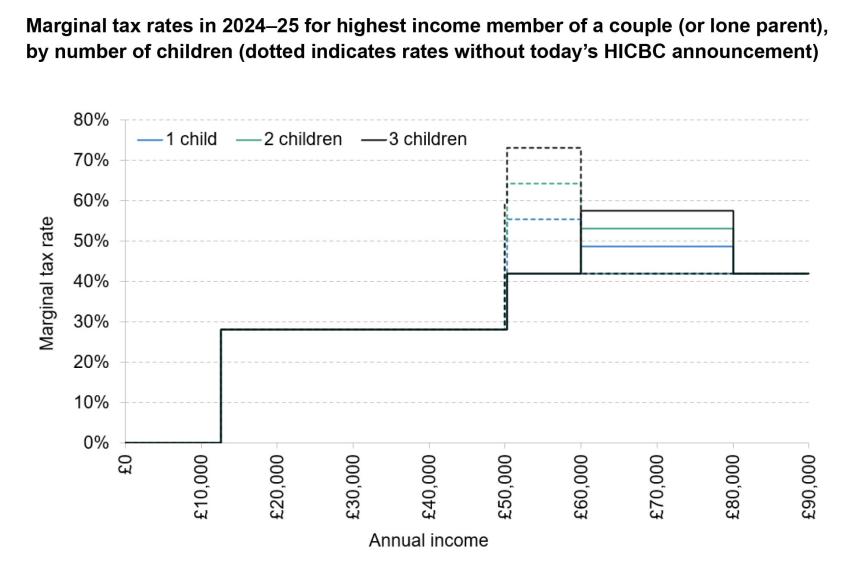

- Increasing the point at which families start losing child benefit from £50,000 a year (for the highest-income parent) to £60,000 will mean that about 170,000 fewer families are affected in 2024–25.

- Halving the rate at which child benefit is withdrawn will further dampen the impacts of HICBC and will mean that families where no parent has an income above £80,000 per year will be entitled to some child benefit (compared with £60,000 under the current system). The HICBC creates particularly high effective marginal tax rates for those with several children. This will remain the case but the impact will be lessened, as shown by the chart below.

- In combination these changes are expected to increase child benefit by an average of £1,260 a year to 485,000 families in 2024–25. After accounting for behavioural changes – including increased take-up – the OBR estimates the cost will be around £0.4 billion a year.

- The HICBC is in need of reform. The current design of the HICBC means that families with the same combined income can be treated very differently depending on how the income is distributed between parents. To address this the government now plans to withdraw child benefit based on family income rather than on the individual income of the highest-income parent from 2026. There will be practical implementation challenges and so the consultation period is sensible.

Public finances

- The OBR has slightly reprofiled its forecast for economic growth, with downward revision to growth in 2023 and 2024 counterbalanced by growth later in the forecast period. By the end of the forecast period, the economy is expected to be the same size in real terms as was thought in the autumn.

- Economy-wide inflation is also expected to be lower in the short term, leaving the cash size of the economy about 0.3% smaller by the end of the forecast period than expected in November. This is associated with a modest downward revision to tax revenue, partially reversing the large fiscal gain seen when the forecast for economy-wide inflation was revised up last November.

- Lower forecast spending on debt interest due to lower expected interest rates and inflation than in November largely contributed to a downward revision of public spending of 0.2% of national income.

- Before taking account of the measures announced today, the medium-term borrowing forecast is essentially unchanged. Policy measures announced today are front-loaded and, in the medium term, add 0.1% of national income (£4 billion) a year to borrowing. While favourable movements in interest rates and inflation expectations help reduce borrowing in the short term relative to the November forecast, borrowing this year, at £114 billion, is still expected to be more than twice the £50 billion forecast in the March 2022 Budget before the onset of the cost-of-living crisis.

Public spending

- The Chancellor left his provisional post-election spending plans effectively unchanged, despite reports that he would cut them back to ‘fund’ tax cuts. Those plans still look devilishly difficult to deliver. Sticking to them would require cuts to unprotected services (those not lucky enough to be covered by existing commitments and promises) of around 3.3% per year, under a plausible set of assumptions. This compares with cuts of 6.1% per year to those areas between 2009–10 and 2014–15, and increases of 5.2% per year over this parliament.

- Some of the few notable spending announcements today related to the NHS. First was an additional £2.5 billion of day-to-day spending for 2024–25. As we highlighted earlier this week, this seemed inevitable at some stage in order to prevent a real-terms spending cut between this year and next. Second was an additional £3.4 billion of capital funding for the NHS in England, to fund investments in technology and productivity-enhancing service improvements. This is a sensible area to focus on, given lingering post-pandemic productivity issues in NHS hospitals. But all of this investment spending is to come after the election, from 2025–26 onwards. The Chancellor has, in effect, announced ‘extra’ spending relative to a baseline that doesn’t exist. He has promised this extra spending, but it will be for the next government to deliver (and fund) this in the next Spending Review.