This week marks the celebration of the Queen’s Platinum Jubilee – 70 years since she became Queen in 1952. Who are the Platinum Jubilee generation, those born when the Queen started her reign? Looking at the generation of people who were born in 1952 helps us to understand the changes that have occurred in British society over the last 70 years, and what a different world we now live in compared to the world of the 1950s.

First, and potentially most importantly, of those born in 1952, 76% of men and 84% of women are still alive, making it to age 70. This is a triumph in itself. This generation has benefited from dramatic increases in life expectancy. If we go back to look at those born in England and Wales a further 70 years before the Queen came to the throne, in 1882, just 34% of men and 45% of women are estimated to have survived to 1952 and their 70th birthday.

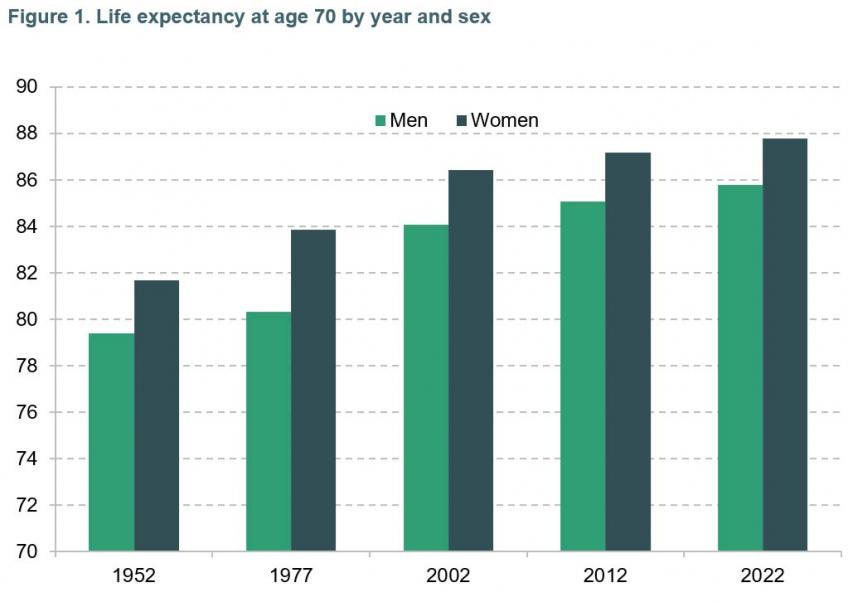

Figure 1 shows that those members of the Platinum Jubilee generation alive today have a life expectancy of 86 for men and 88 for women. Compared to those turning 70 in 1952, that is an additional 6 years of expected lifespan for both men and women. A small but growing share are expected to make it to receive a Royal greeting on their 100th birthday. Of the Jubilee generation alive today, just over one-in-forty men and just under one-in-twenty women are expected to be alive in 2052.

The Figure also shows life expectancy at 70 at the Queen’s other Jubilees in 1977, 2002 and 2012. Since the rapid increase in life expectancy at age 70 that took place between the Silver and Golden Jubilees, the progress has slowed.

Source: Authors’ calculations using ONS life tables

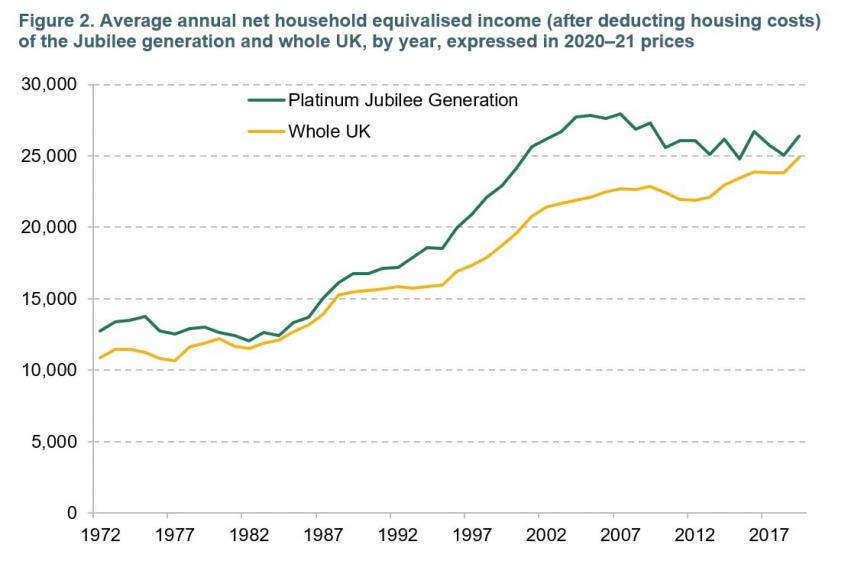

The Platinum Jubilee generation are also the richest in history so far. As shown in Figure 2, they have average household incomes (after accounting for household composition and housing costs) that are higher than the population as a whole and higher than the incomes they themselves had over most of their working lives. This generation benefited from the strong growth in earnings in the 1980s and 1990s in particular, and from the increasing generosity of the state pension in more recent years.

When they were 25, at the time of the Silver Jubilee, their average incomes were £12,500 (expressed in 2020–21 prices), compared to £10,700 for the whole of the UK. The peak of their incomes came just after the Golden Jubilee when, in 2005, they had average incomes of £27,800, a full £5,700 higher than the UK average. They now have incomes of £26,400 per year, 6% (£1,500) more than the average.

Source: Authors’ calculations using the Family Resources Survey and Family Expenditure Survey. Figures are for Great Britain only before 2002

Many in this generation rode the wave of the UK’s property price boom. 85% of them are homeowners and 14%, or one-in-seven, own a second home. In 1952, the average property price was £2,000 (around £40,000 in today’s prices); that rose to £13,000 by 1977 (around £64,000 in today’s prices) and today stands at £260,000.

Of course, not all of the Jubilee generation are well off. 18% were in relative income poverty prior to the pandemic (compared to 22% for the UK as a whole). But this still represents a remarkable change: in 1977, the Silver Jubilee year, those over state pension age were more than twice as likely to be poor as those under state pension age.

The Platinum Jubilee generation have led varied lives. 15% have a degree or equivalent higher education – much lower than the fraction of younger generations. Three quarters are married, but 10% are widowed and 11% divorced or separated from a partner. The English Longitudinal Study of Ageing has followed this group since the time of the Golden Jubilee. From those data, we know that 43% of the Platinum Jubilee generation report ever having been a regular smoker while just 9% are still smokers today.

As they move into older age, they are getting to the point where – for many – their health is starting to become a problem. 35% of them are taking some medication for high blood pressure and just over one-in-ten report difficulties dressing themselves. While 11% of them still say that their health is excellent, 7% say they are in poor health.

The future

While the generation born as the Queen came to the throne in 1952 have seen huge changes, what changes will be experienced over the lifetimes of those being born this year? The uncertainty is huge, of course. Some trends are anticipated to continue, with a staggering one-in-seven boys and one-in-five girls born this year expected to live to 100. Some trends will likely change: although younger generations are much more educated than the Platinum Jubilee generation, with around half now attaining a university degree, income growth is not expected to be as strong in the future as it was over the Queen’s first 50 years on the throne.

There are challenges ahead. The large rises in house prices enjoyed by the Platinum Jubilee generation have seen homeownership rates fall for younger adults. Will those rates recover again or will we see generations where a large proportion are private renters throughout their lives? Perhaps the greatest changes will come in pursuit of rapid de-carbonisation of the economy. By the time the first member of the Jubilee generation receives a 100th birthday card, we will know whether the 2050 net zero target has been met.