Paul Johnson, IFS Director, said:

“Today, the Chancellor announced the biggest package of tax cuts in 50 years without even a semblance of an effort to make the public finance numbers add up. Instead, the plan seems to be to borrow large sums at increasingly expensive rates, put government debt on an unsustainable rising path, and hope that we get better growth. This marks such a dramatic change in the direction of economic policy-making that some of the longer-serving cabinet ministers might be worried about getting whiplash.

Mr Kwarteng has shown himself willing to gamble with fiscal sustainability in order to push through these huge tax cuts. He is willing to shrug off the risks of inflation, and to invite significantly higher interest rates. And he has avoided scrutiny by presenting a Budget in all but name without accompanying forecasts from the Office for Budget Responsibility.

Injecting demand into this high-inflation economy leaves the government pulling in the exact opposite direction to the Bank of England, who are likely to raise rates in response. Early signs are that the markets – who will have to lend the money required to plug the gap in the government’s fiscal plans – aren’t impressed. This is worrying. Government borrowing is set on an upward path. It will reach its third-highest peak since the war, and remain at well over £100 billion, even once the energy support package is withdrawn.

And we heard nothing on public spending. It seems almost inconceivable that plans made last year, when inflation was expected to peak around 3%, will not need topping up at some point, unless the government is willing to allow a (further) deterioration in the range and quality of public services. Presumably this government would borrow for that also.

Mr Kwarteng is not just gambling on a new strategy, he is betting the house.”

Public finances

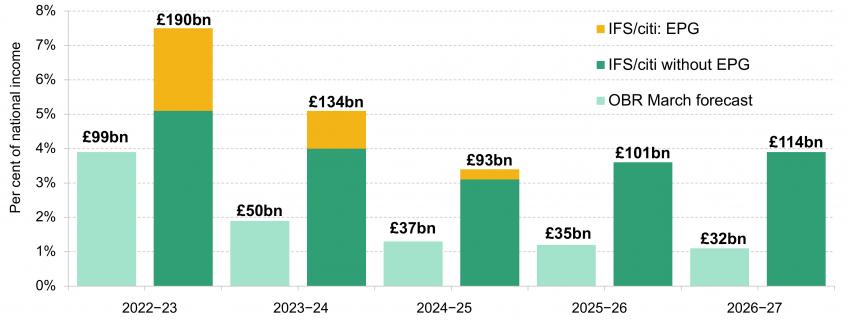

The Government’s costing of the Energy Price Guarantee for households and non-domestic consumers - £60 billion over the next six months - means that borrowing this year is now on course to climb to £190 billion. At 7.5% of national income this would make it the third-highest peak in borrowing since the Second World War, after the Global Financial Crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic.

By 2026-27 we now forecast that borrowing will be over £110 billion - 3.9% of GDP - which is more than £80 billion higher than the £32 billion forecast by the Office for Budget Responsibility in March. Over half of this increase in borrowing is due to the almost £45 billion a year of tax cuts announced by the Chancellor today.

Our forecasts make no allowance for any top-up to spending on public service spending which might be required given the myriad pressures they face and the fact that public-sector pay awards will run at a much higher rate than assumed when the spending envelope was set a year ago. We also do not account for the most recent rises in gilt rates: the interest rate on 10-year government bonds is currently running at 0.5 percentage points higher than on just Thursday morning. A sustained increase in the cost of government borrowing of this magnitude would add £5 billion a year to borrowing.

Borrowing at the rate we forecast would see debt continuing to rise as a share of national income even after the Energy Price Guarantee has expired.

It is possible that economic growth will be higher than expected, either through luck or through concerted policy reforms across government. But on current policies it is more likely that, at some point, today’s tax cuts will need to be paid for by future tax rises or spending cuts.

Public sector net borrowing forecast with and without Energy Price Guarantee (EPG) (23 September 2022)

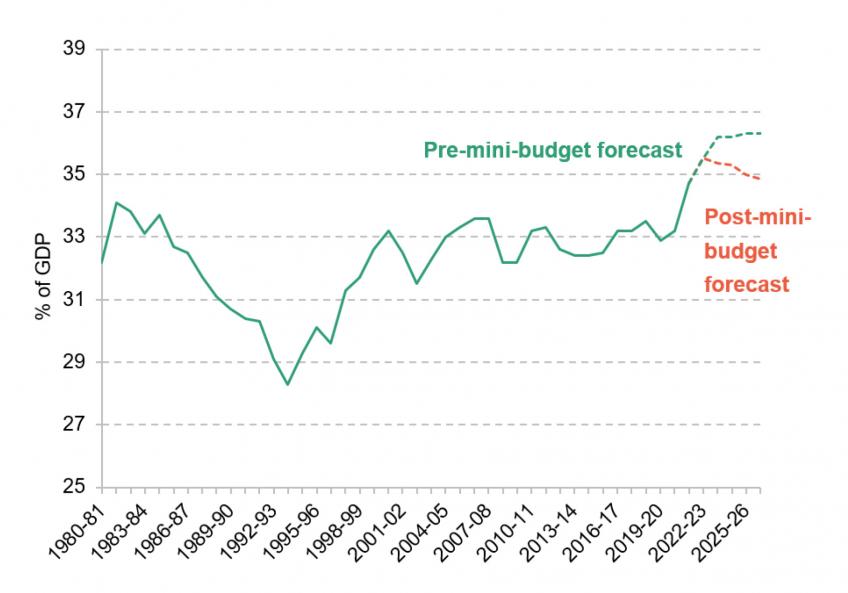

Underlying government debt forecast as a percentage of national income (23 September 2022)

Tax cuts - the big picture

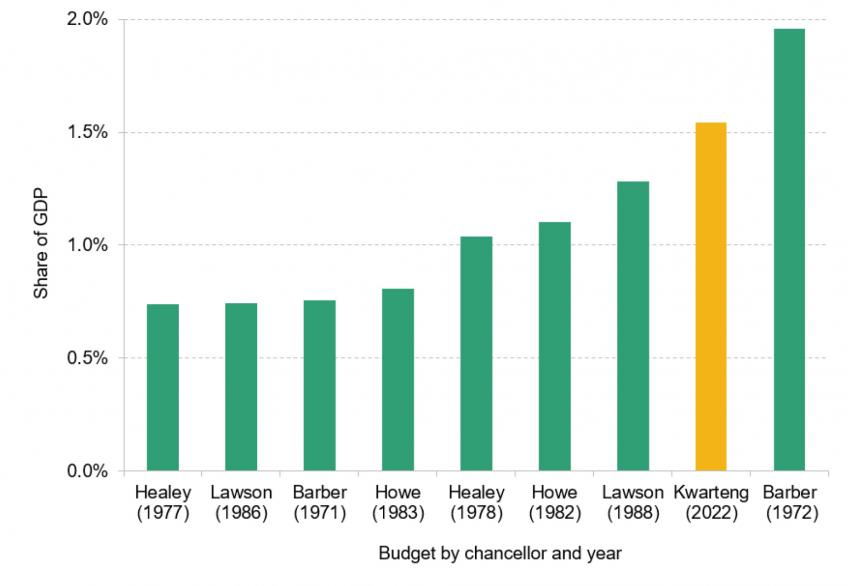

Today’s ‘mini-budget’ is anything but mini. In fact, it represents the biggest tax cut to the planned level of tax of any budget since 1972, outdoing even Nigel Lawson’s 1988 Budget in which the top rate of income tax was reduced from 60% to 40%.

Net permanent tax cuts as a percentage of GDP, relative to previous plans

While the tax reductions announced in this budget are substantial, their impact is only forecast to return the UK tax burden to 2021-22 levels – reflecting the large increases in the tax burden previously forecast for the coming years. This will mean a tax burden that remains at its highest sustained level since the 1950s.

UK tax burden as a share of GDP

Income tax and National Insurance contributions

Chancellor Kwarteng has announced some broad-based tax cuts that will affect tens of millions of people, and one tax cut aimed very narrowly at the 600,000 people (1.1% of adults) on the highest incomes.

April’s 1.25 percentage point (ppt) increases to the rates of employer, employee and self-employed National Insurance contributions (NICs), and to the rates of income tax on dividends, will be reversed from 6 November. Workers with annualised earnings above £12,570 gain from the NICs cut. The health and social care levy, which was effectively going to extend that NICs increase to workers aged over the state pension age from next April, will not be implemented. This will cost about £16 billion per year from next year.

A 1ppt cut to the basic rate of income tax announced previously by then-Chancellor Rishi Sunak, from 20% to 19%, has also been brought forward by one year to April 2023. Hence income taxpayers will gain for an additional year from a tax cut worth an average of £125 per year for basic-rate taxpayers, and £377 per year for all higher-rate taxpayers, at a one-off cost to the exchequer of around £5 billion.

Finally, the 45% additional rate of income tax applying to incomes above £150,000 per year will (for those living outside Scotland) be abolished from April. Instead the 600,000 people currently paying this additional rate - about 1.1% of adults - will simply pay the standard “higher rate” of 40%.

The government says that cutting the top rate from 45% to 40% will cost about £2 billion per year. If no-one increased their declared taxable income in response to the change, we estimate that it would cost about £6 billion per year: hence, the government is assuming that roughly two-thirds of the mechanical reduction in revenue is recouped due to behavioural responses. That looks like a plausible estimate, but the main thing to emphasise is the large uncertainty around it: it is not implausible that it will cost significantly more than £2 billion. It might plausibly cost nothing at all.

The number of additional-rate taxpayers has steadily grown over time, from about 200,000 when it was introduced in 2010 to about 600,000 today - a consequence of the £150,000 threshold being frozen in cash terms for its entire existence.

The mechanical cost of £6 billion, and 600,000 additional-rate taxpayers, implies an average gain of around £10,000 per additional-rate taxpayer. The number is so high because a small number of extremely high-income individuals will gain so much. It takes an income of around £600,000 a year to make it into the top 0.1% of taxpayers. They will each gain at least £22,000. Those with incomes in excess of £1 million will gain more than £40,000 a year each.

One major set of tax increases that has not been reversed is the freeze in the personal allowance and the higher- and additional-rate income tax thresholds. These are set to run until the end of the parliament. With inflation now so high, those freezes represent big income tax rises. (Note also that the rise in the NICs threshold that took effect this year will be almost completely eroded by inflation by 2025–26, since the NICs threshold is being frozen going forward.)

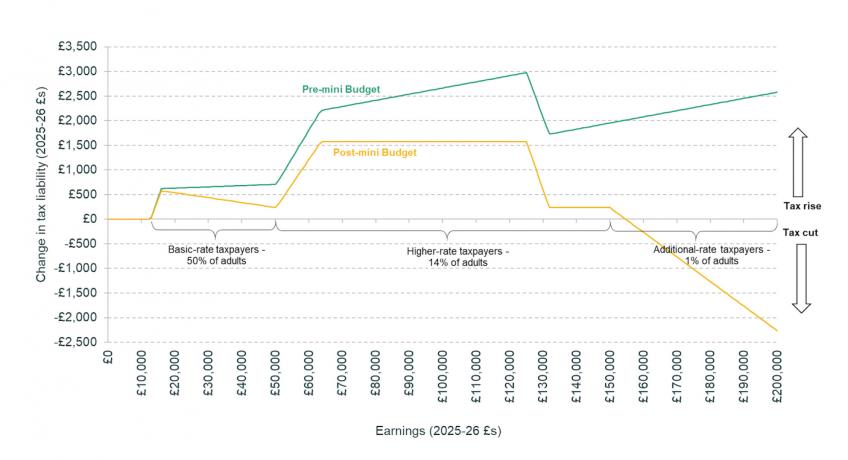

The chart below illustrates the combined impact in 2025-26 of all reforms to income tax and NICs introduced since 2021-22, announced before and after this mini-Budget (i.e. without and with the cuts to NICs and to the additional rate of income tax). The combined effect of these changes is still to leave the vast majority of income tax payers paying more tax. The biggest losers in cash terms will be those earning between £63,000 and £125,000. They will be paying £1,570 more in direct tax in 2025-26 than if no changes had been made.

Only those with incomes over at least £155,000 will be net beneficiaries. They gain from the abolition of the additional rate, and are unaffected by freezing the personal allowance because their incomes are too high to be eligible for one anyway. This is quite a different picture from that before the mini-Budget, which implied larger tax rises across the board, but especially so for higher earners.

Impact of income tax and NICs changes introduced from 2021-22 to 2025-26 on tax liabilities in 2025-26 (in 2025-26 prices; expected number of taxpayers in 2025-26 shown)

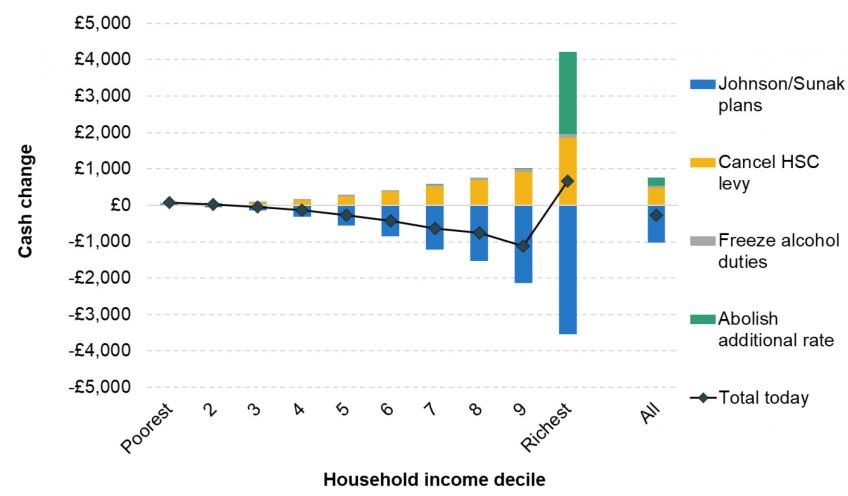

Taken together, today’s measures undo much of the tax rises introduced by Johnson and Sunak, and undo all of them for the highest-income households. The losses for middle- and higher-income households from previously introduced policies will be roughly halved by today’s measures. The richest tenth of households, who were set to lose around £3,500 a year (3%) on average in 2025-26 under Johnson and Sunak’s plans, will now gain around £700 a year (1%) on average.

Distributional impact of personal tax and benefit measures implemented since November 2021, 2025-26 in 2022-23 prices

Note: Assumes employer NICs incident on workers. Assumes additional rate is also abolished, but basic rate not changed, in Scotland.

Corporation tax and the annual investment allowance

The cancellation of the planned cut to corporation tax is one of the biggest measures in today’s statement. The Treasury forecasts that it will reduce revenue by around £15.4 billion a year (in 2022-23 terms). It will help to increase investment in the UK and therefore boost UK GDP, meaning that the long-run cost of the policy will almost certainly be lower than this. However, the evidence is clear. The cut will not pay for itself.

Setting the annual investment allowance (AIA) – the amount of spending on plant and machinery that businesses can deduct immediately from their taxable profits – permanently at £1m is welcome, reducing disincentives to invest and simplifying the tax system. It will be especially welcome if it really does prove to be permanent: instability and unpredictability in the level of the AIA has been a major problem in the past.

The long-run cost will be much lower than the £1.3 billion a year shown in the government’s costings, because deducting the cost of investment immediately rather than gradually means that businesses will pay less tax in the year they invest but correspondingly more tax in later years. Most of the cost is delaying revenue rather than reducing the cash amount, though there will still be some long-run cost to the exchequer.

Stamp duty land tax

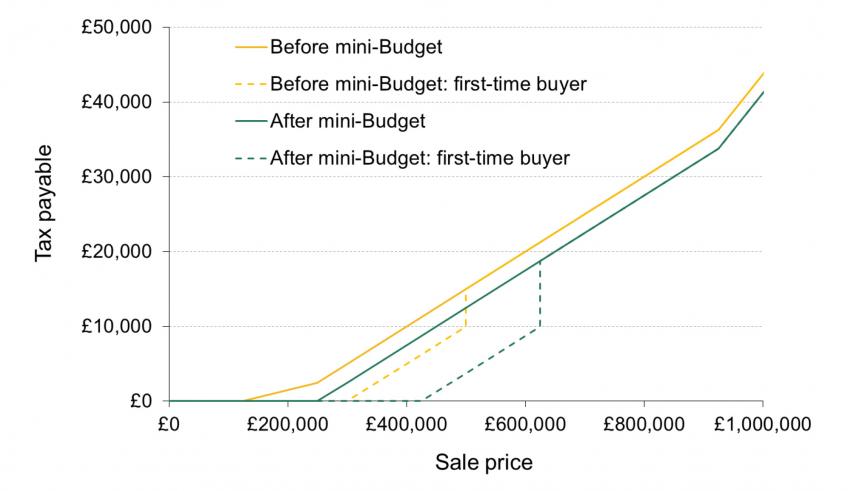

Reducing the burden of stamp duty land tax on housing (at a cost of around £1.4 billion a year in today’s terms) is a welcome reduction to a tax whose impact is to deter mutually beneficial property transactions. It will make it easier for people to upsize, downsize or move to where better job opportunities are available. The tax on a property purchase in England or Northern Ireland will fall by up to £2,500 (if the price is more than £250,000, or less if the price is between £125,000 and £250,000) – and by up to £11,250 for first-time buyers (if the price is between £500,000 and £625,000, with those buying for between £300,000 and £500,000 gaining less).

Stamp duty land tax on housing

The main beneficiaries will be existing homeowners, whose properties will be worth more than in the absence of the reform, though first-time buyers will also benefit from the increase in the generosity of relief for them.

An unfortunate side-effect of the poor design of first-time buyers’ relief is that increasing the relief increases the size of the cliff-edge where it is withdrawn: someone buying their first property for £625,001 will pay £8,750 more tax than someone buying for £625,000.

Investment Zones

The government intends to create new Investment Zones getting special treatment for tax, regulation and local governance. The full details, and therefore the cost, have not yet been confirmed.

Tax sites within the new Investment Zones will offer a raft of temporary business tax reliefs similar to those available in Freeports, but even more generous and for ten years rather than five. These tax breaks are likely to increase economic activity in these areas, but some of that would otherwise have happened elsewhere in the UK.

This raises the question of why it is better to have lower taxes in some parts of the country than others – encouraging people and businesses to move to the favoured areas – rather than spending the same money on (smaller) tax cuts spread evenly across the country: for example, whether it is intended to help ‘level up’ deprived areas and, if so, whether the areas and policies chosen are appropriate for that objective.

Since the tax breaks are temporary, another question is how much businesses will find it worth making long-term investments that will tie them into the area for longer than that – and, correspondingly, how much the economic benefits to favoured areas will persist after the tax breaks expire.

Off-payroll working rules

The ‘off-payroll working’ rules, often known as IR35, determine whether someone supplying their services is working through their own business or is really an employee for tax purposes, which would attract higher tax.

The Chancellor announced that he would move responsibility for determining a person’s status back to the individual rather than those engaging their services, reversing changes made in 2017 and 2021. In principle this does not change the amount of tax that is due, because it does not change the person’s ‘true’ status. But the government estimates that it will reduce revenue by about £2 billion a year. This is because it reduces the risk that, out of an abundance of caution, firms classify too many people as employees (with more tax paid than is really necessary), and increases the opposite risk that ‘too many’ individuals will declare themselves to be working through their own business (with too little tax paid).

The broader objective should be to reduce or eliminate the difference in tax payable according to the legal form in which people work (while protecting incentives for investment and risk-taking), so that such essentially arbitrary classifications do not matter and commercial decisions about the best way to organise work are not distorted by tax policy.

Public spending and public services

Today’s fiscal event was almost entirely focused on tax; there were precisely zero new public spending announcements. There was one change, however, made as a result of the cut to National Insurance contributions (NICs) – though this wasn't published anywhere in the official documents, and was made apparent only following a discussion with HM Treasury. When then-Chancellor Rishi Sunak increased NICs in 2021, he also provided around £2 billion of extra funding to public services each year to compensate for the additional employer National Insurance costs. Kwasi Kwarteng has now reversed the NICs rise. From 2023-24, the Treasury is withdrawing that compensation from departments: the employer NICs cut means their staffing costs will be lower, and their budgets will be reduced by a commensurate amount. Public services will be no worse off as a result of this change (had the compensation been left in place, they would have been better off). On aggregate, spending plans are left unchanged, because the money will be taken from departments and moved into the Reserve, to be used to meet any unforeseen future costs in future years (such as the costs of any military aid to Ukraine). It is important to remember, though, that due to higher-than-expected inflation, public services are still worse off than they were intended to be when public spending plans were set out last year. Departments have been told to pay for the costs of higher-than-expected pay awards from within existing budgets. A tough winter for public services lies ahead.

Note: the final section on public spending and public services has been edited to reflect the fact that departmental budgets are being altered to reflect the reduction in employer National Insurance contributions.

Image: Richard Lincoln / Alamy Stock Photo