Summary

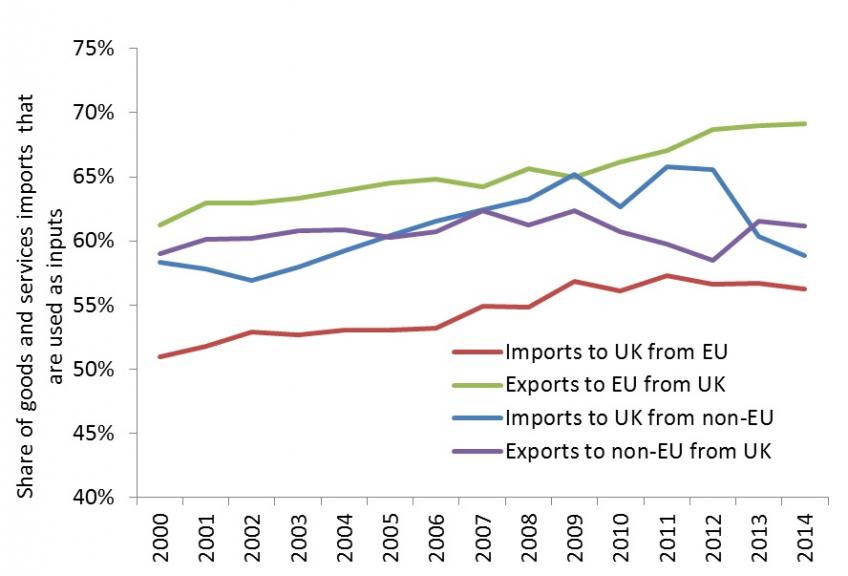

We often think of exports and imports as things made in one country and consumed in another – I export cars to you and import socks you’ve made. In fact, the majority of UK exports and imports are now made up of goods or services that are themselves inputs into production – I export engines to your car factory and import cotton to make into socks. This sort of trade is particularly important for understanding the UK’s trade with the EU. Over half of the UK’s imports from the EU are of such intermediate goods and services, as are nearly 70% of our exports to the EU. These shares have also been growing over time.

This pattern of interdependence is crucial for understanding trade policy. Outside the single market and customs union, UK trade would still be affected not only by the trade deals it strikes with other countries but also by the trade deals the EU has with third parties. Moreover, in such an interdependent world, multilateral trade agreements are much more valuable than bilateral ones. As a result, even if the UK decides to make its own way in striking future trade deals, it will still pay to coordinate its efforts with others – including the EU.

Full version

Globalisation, and the accompanying internalisation of firms’ supply chains that has occurred over recent decades, have changed the way we should think about trade flows and in particular the UK’s trade with the EU. It is increasingly the case that countries’ exports embody imports from abroad, whether in the form of imported raw materials, components or business services.

Supply chains play a particularly important role in UK-EU trade. Not only is the EU the UK’s largest source of imports (accounting for 54% of the total in 2016), but a majority of these imports now take the form of intermediate goods and services. These are goods or services that add to the value of a product which firms then sell either for further processing or for final consumption. Tin used to produce a can is an intermediate good. A tin of beans sold to a supermarket for sale to consumers is not.

Nearly 70% of the UK’s exports to the EU take the form of intermediate inputs to production of other goods and services. The relative importance of the EU in the UK’s trade thus largely reflects the role UK industries play in EU-wide supply chains.

Figure 1 shows the importance of intermediate goods and services in the UK’s trade with EU and non-EU countries, and how this has changed over time, using figures calculated from the World Input-Output Database. The share of goods and services imported from the EU that are used in the production of UK goods and services rose from 51% in 2000 to 56% in 2014. The remainder was made up of goods and services intended for final consumption.

Figure 1. Share of intermediate goods and services in the UK’s imports and exports, 2000–14

Source: Author’s calculations from World Input-Output Tables, 2016 edition.

The share of intermediate inputs in imports from the EU is similar to (in fact slightly lower than) their share in imports from the rest of the world. However, intermediate goods and services tend to be more important in the UK’s exports to the EU than in its exports to other destinations. The share of the EU’s imports from the UK that were intermediate goods and services was 69% in 2014 (having increased from 61% in 2000).

In total, 9.3% of the UK’s inputs are sourced from the EU. However, the degree to which different UK industries make use of inputs imported from the EU varies greatly (Figure 2). They are most important for UK manufacturers, who obtain 16% of their inputs from the EU, followed by healthcare and agriculture, which obtain 13% and 11% of their inputs from the EU respectively. Inputs from the EU are, perhaps unsurprisingly, less important for service industries such as real estate. Within the manufacturing sector, the industries that make most use of EU inputs are motor vehicles, pharmaceuticals, chemicals and electronics – incidentally, industries which also tend to export relatively more of their output to the EU.

Looking instead at the importance of UK inputs for industries in the rest of the EU, the first thing to note is that the UK is a much less important source of inputs for the EU than vice versa. For example, manufacturing firms in the rest of the EU only obtain 1.5% of their inputs from the UK. One industry in which UK inputs are noticeably more important than others, however, is financial intermediation: 3.3% of inputs to the rest of the EU’s financial intermediation sector come from the UK. The total proportion of the EU’s inputs sourced from the UK is 1.4%.

Figure 2. Share of inputs imported from the EU (for UK) or the UK (for EU) by industry, 2014

Source: Author’s calculations from World Input-Output Tables, 2016 edition.

These facts have a number of immediate implications for the way the UK should think about its future trade policy, in terms of its trading agreements with the EU and with the rest of the world.

1)The increasingly interconnected nature of global trade means that a country’s imports and exports cannot be treated as independent quantities. A successful exporting country will also need to be open to imports. Exports embed imports, and so greater access to imports can boost the competitiveness and export performance of domestic firms. For example, according to the OECD TiVA database, 9.5% of the value-added embedded in the UK’s gross exports in 2011 was produced in the EU and a further 13.5% was produced in the rest of the world. These figures represented increases from values of 8.2% and 9.6% respectively in 2000. As a result, UK firms’ access to imports as well as export markets is an increasingly important consideration for future trade policy. The UK should take this into account before taking actions that would introduce or maintain tariffs or other trade barriers on its imports from the EU or third countries.

2)Demand for the exports of UK industry depends not only on the export access of UK-based firms but also on the export access of firms they supply. Since the UK is a relatively important supplier to EU firms, the trade deals the EU signs will continue to have relevance for the UK in the coming years, whether or not the UK leaves the customs union. This includes, of course, the access the EU has to the UK market.

3)The importance of international trading networks means that bilateral trade deals will tend to be of less value than multilateral deals. This is partly because of the importance of rules of origin requirements, which can create a complex ‘spaghetti bowl’ of overlapping agreements which firms involved in international supply chains must navigate in order to benefit from bilateral trade agreements.

For example, in the EU-Korea free trade agreement, a good exported from the EU is deemed to have ‘originated’ in the EU only if less than 45% of the value of inputs has been imported from outside Korea or the EU. At present, UK imports from other EU countries therefore do not count as ‘foreign’ when determining a product’s origin and so do not limit firms’ ability to sell their goods to Korea. Equally, EU firms can freely use components manufactured in the UK. Outside the EU, the UK may well be considered a third party in such trade agreements and hence EU firms may not be able to use too many UK components in exports to Korea. Since foreign components are an important input for UK manufacturers, many firms may not be able to benefit from bilateral deals the UK signs unless the UK can get its partners to agree to less restrictive rules of origin requirements (and there may be a price to pay for this). The more countries that are included in each deal, the less of a problem this will be.

A final question is whether the current importance of inputs from the EU is likely to change following Brexit. If the EU’s own tariffs exclude competition from the rest of the world, then selective post-Brexit tariff reductions on imported goods could help to improve the competitiveness of UK firms.

This effect is likely to be small though. First, tariffs on the sort of intermediate goods the UK purchases from the EU (and indeed the rest of the world) already tend to be lower on average than those levied on goods used for final consumption – about 4% on intermediate goods compared with nearly 10% on goods imported for final consumption. These figures would be even lower if we took into account services inputs that essentially attract no tariff. Second, tariff reductions will not prevent the introduction of non-tariff barriers such as customs checks that would follow if the UK left the EU’s customs union and single market. These are especially important considerations for industries that value timeliness and flexibility in their supply chains (such as the car industry), and would be difficult to negotiate away in deals with third countries.

Notes

This analysis was funded by the Economic and Social Research Council’s ‘The UK in a Changing Europe’ Initiative and also appears as a blog on their website.