Heidi Karjalainen, a Research Economist at IFS said:

"The inflation figures out today mean that – if the government uprates benefits with inflation, as is typical – most working-age benefits will go up by 10.1% in April. But this would still leave their real value on course to be 6% below their pre-pandemic levels, equivalent to almost £500 per year for the average out-of-work claimant – and even this assumes that benefit recipients will continue to receive equivalent support for rising energy bills as they do under the (now shorter-lived) Energy Price Guarantee. This is a consequence of below-inflation increases in April this year, when benefit rates failed to keep pace with an accelerating rate of inflation. The situation for benefit recipients’ living standards next April could be even more difficult depending on the design of the energy support package in place from next April.”

- This morning the ONS announced that CPI inflation rose to 10.1% in the year to September.

- Working age benefits are generally uprated every April in line with the previous September’s CPI inflation figure, so if no changes are made to uprating before next spring, working-age benefits will increase by 10.1% in April 2023.

- In periods where the rate of inflation is increasing rapidly, this lagged measure of inflation leaves the UK’s 6 million working age households that receive benefits (other than child benefit) temporarily short-changed, as happened already in April 2022. Some of the shortfall in the real value of benefits this year was made up for with a number of one-off grants, the last of which will be paid in March. The uprating that will take place in April 2023 will not undo this shortfall, leaving benefits 6% below their pre-pandemic levels. For the average out-of-work household on working-age means-tested benefits, this represents an almost £500 per year real decline in income. This assumes that the new targeted support measures the Chancellor has mooted fully make up for the expiry of the Energy Price Guarantee (EPG) in March, but this is far from certain.

- In recent weeks, there has also been speculation that the government might change the working-age benefit uprating index from CPI to average earnings, presumably for April 2023 only. This would reduce benefit spending on working-age benefits by roughly £7bn in 2023-24 (or £5bn if health related benefits still went up by inflation), because CPI inflation in September was 10.1%, whereas average earnings are growing at a much slower rate of 5.5%. Even if the government returned to inflation uprating in 2024, this choice would lock in a permanent real-terms cut to the benefit system.

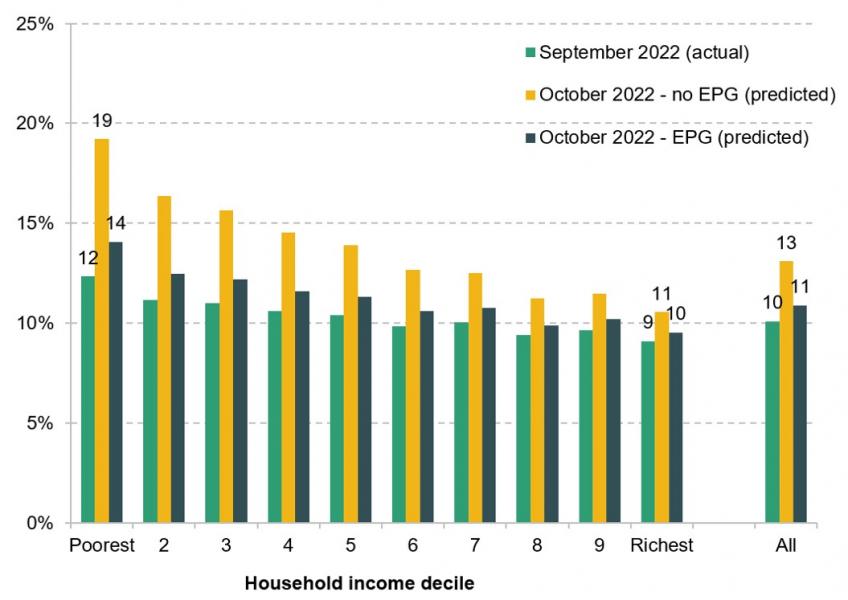

- Moreover, inflation rates are even higher than the headline figures suggest for poorer households, as they spend more of their household budgets on energy. As shown in Figure 1, even with the Energy Price Guarantee, in October this year the poorest tenth are expected to have faced an average inflation rate of 14% compared to 10% for the richest tenth. This compares to a rate of 19% for the poorest 10% if the EPG had not been in place.

- Regardless of the details of the new support package, the government should switch to using more up-to-date information to uprate benefits. This would avoid the kind of situation we are now in, where claimants – both working-age households as well as pensioners – have to wait long periods for benefit payments to catch up with prices.

Figure 1. CPI inflation by income decile

Source: Authors' calculations using Living Costs and Food Survey (LCFS) 2019, and consumer prices data from the Office for National Statistics. The no EPG inflation scenario assumes Ofgem tariff cap of £3,549.