Hundreds of thousands of young people are in the process of applying to university, in time for a 2018 start. Their choices can make a huge difference to future earnings.

For most university graduates, having a degree pays.

Over the course of a lifetime, estimates suggest women can expect to earn about £250,000 more if they have a degree, while the figure is roughly £170,000 for men.

In England, higher tuition fees mean that, on average, students graduate with debts of more than £50,000 - much more than their counterparts in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland.

But repayments are only one of many factors which affect how much money graduates will have in their pockets in years to come.

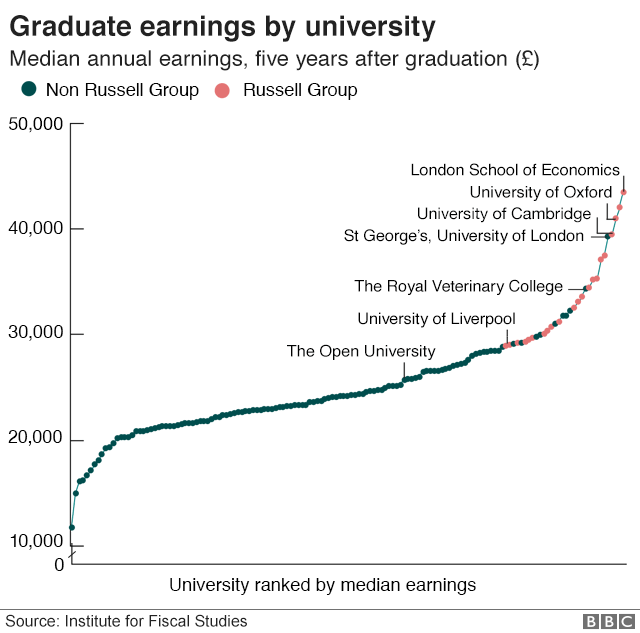

The universities which attract the highest incomes

Perhaps unsurprisingly, there are big differences in the earnings of graduates from different universities.

Five years after graduation, average annual earnings for students who were taught at the London School of Economics, Imperial College London and University of Oxford are more than £40,000.

Graduates of the 24 Russell Group universities earn an average of £33,500 after five years - about 40% more than those who studied at other universities.

At the other end of the scale, there are several institutions - many of them dance and drama colleges - where average earnings after five years are closer to £15,000.

Importantly, many of the differences here are not down to the universities themselves.

They have different average earnings partly because students aren't all the same - they have different abilities and interests.

Entrants to Oxford, LSE and Russell Group universities start their degrees, on average, with better exam grades, for example.

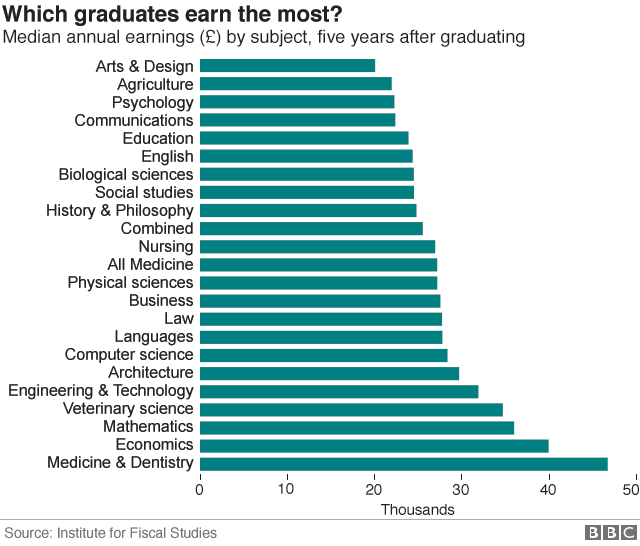

The big decision about what to study at university can be very important for future earnings.

Five years after graduation, the income gap between students who studied the subjects that attract the highest and lowest salaries can be considerable.

Graduates of medicine and dentistry earn an average of £46,700, while those who studied economics take home £40,000.

These figures are about double the average wages of creative arts (£20,100), agriculture (£22,000) and mass communication (£22,300) graduates.

Crucially, these differences are smaller, but remain significant, even when students with similar A-level grades are compared.

As careers progress the gaps get bigger, with graduates of the high-earning subjects pulling even further away.

For example, students of law, economics and management subjects at the London School of Economics do extremely well, with 10% of male graduates earning more than £300,000 by the time they are in their early 30s.

Sexual inequality

A number of factors influence graduate earnings long before they get as far as choosing which course to study, or which university to attend.

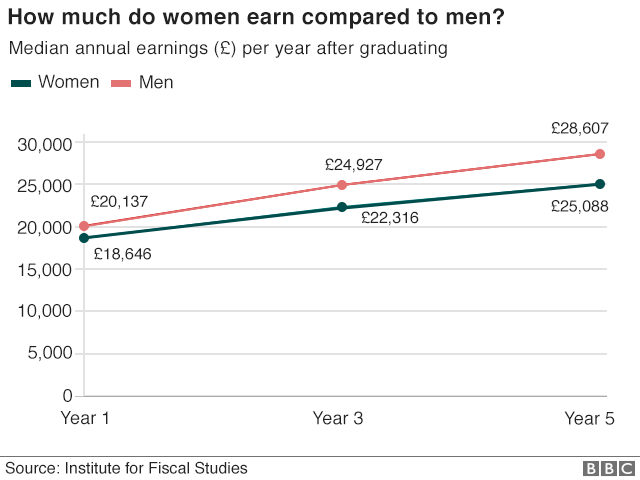

In particular, the reality is that male graduates earn more than female graduates.

The gap can already be seen only one year after graduation, when men earn an average of £1,500 (8%) more than women per year.

After five years, the gap has increased to around £3,500, or 14%.

This is likely to continue to increase with age, but it should be noted that this gap is less than half that experienced by non-graduates.

Some - but by no means all - of this difference can be explained by differences in subject choices, with women more likely to choose courses with low earnings potential.

For example, creative arts, nursing, psychology and social science all have far more female than male students, while the opposite is true for architecture, computing and engineering.

However, a large part of this difference cannot be explained away by personal choice.

Rich vs poor

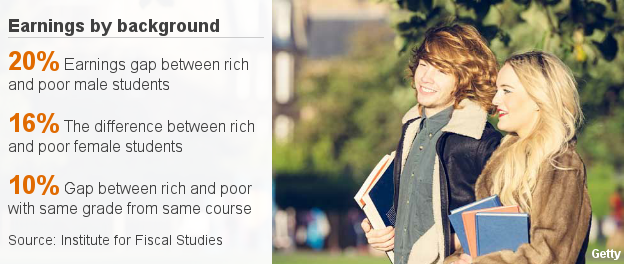

The social background of students also matters.

Those from better off households are much more likely to go to university.

They are also much more likely to go to more selective universities.

That is a large part of the reason why male graduates from households with incomes above £50,000 earn about 20% (£7,000) more than their university peers from lower income households, by the time they are in their early 30s.

Among women, there is a 16% (£4,000) gap between these households.

Remarkably though, even when comparing students who did the same subject at the same university, those from the richest households still earn around 10% more than their peers from less affluent backgrounds.

This suggests improving access to university alone is not enough to address issues of social mobility.

Never-ending debt

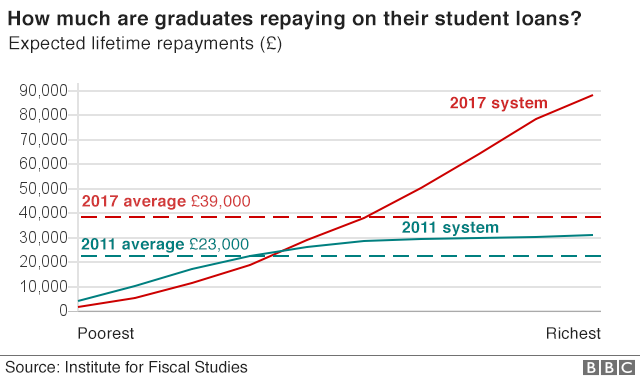

The increase in tuition fees to £9,250 per year in England has significantly increased the level of debt students graduate with - and the repayments many will make over their careers.

Most will in fact not pay back all of the cost of their tuition, with the taxpayer picking up the difference.

Recent changes have offered some respite to those who go on to have low earnings.

Graduates only ever have to pay 9% of their income above a given threshold, regardless of the size of their debts.

The threshold will rise from £21,000 to £25,000 in April 2018, putting more money in the pockets of significant numbers of graduates.

Over the course of their working lives, this could save graduates up to £15,700 in student loan repayments.

It also means that more than 40% of graduates are now expected to repay less than they would have had there been no changes to the student loan system since 2011.

And, for eight out of 10 graduates, it is likely that they will get to the end of their working lives having never paid off that loan.