The Conservative Party manifesto confirmed a long-discussed commitment to find a further £12bn of cuts to the annual social security budget, and to do this by 2017–18. That’s an £11.8bn cut in today’s prices (as all subsequent figures in this observation will be). This observation, funded by the Joseph Rowntree Foundation, briefly summarises previous IFS analysis of the context for these choices and the kinds of options that are on the table.

What is meant by a cut here is that the generosity of the system will be reduced such that annual spending is £12bn lower than it otherwise would have been. Meanwhile wider economic factors or demographic trends might also push spending up or down. But, for example, a fall in benefit spending triggered by an increase in employment would not count as a cut in this sense. Conversely, spending on benefits remained relatively flat over the last parliament, despite net cuts of about £17bn, as underlying pressures such as falling earnings, growing rents, and growing numbers of older people approximately offset the cuts in generosity. As always, of course, in the event of unexpected good or bad fiscal news the government would be left with a choice as to whether to allow the planned path of the deficit to change or to adjust its tax or spending plans (or some combination).

What has already been announced?

Specific benefits policies in the manifesto make a small step towards the specified total. Freezing most working-age benefits and tax credits for two years, rather than increasing them in line with inflation, would – given the current low-inflation environment – cut spending by only £1.0bn under current inflation forecasts. It implies a 1.4% real cut to the affected benefit rates by the end of the two years, which translates into an average loss among the losers of less than £100 per family per year. But it is a very broad-based cut, affecting entitlements for about 11 million families. Freezing these benefits for longer would save significantly more, particularly given that inflation is expected to be higher after 2017–18 than before it. Extending the freeze to the end of the parliament would take another £4½bn off the annual benefits bill under current forecasts. But this is irrelevant for the stated goal of finding savings by 2017–18.

Reducing the benefits cap from £26,000 to £23,000 per year would hit some families with several children and/or high rents hard: the biggest losers would be about 24,000 families who are already capped and who would lose another £3,000 per year (i.e. up to 11.5% of their income). But because in total fewer than 100,000 families would be affected and most would lose less than this, the policy reduces spending by only £0.1bn. Evidence from the current cap (discussed here) suggests that, at least in the short-term, a small minority of affected families will respond by moving into work – the cap does not apply to claimants of Working Tax Credit – and that very few indeed will respond by moving house.

Similarly, removing housing benefit from 18-21 year-old jobseekers would be a significant cut for about 20,000 young adults, but the small numbers affected limit the saving to just £0.1bn. This would increase the incentive for these individuals to move into paid work, or to claim a different out-of-work benefit (Employment and Support Allowance or Income Support) instead.

This leaves a lot not yet announced

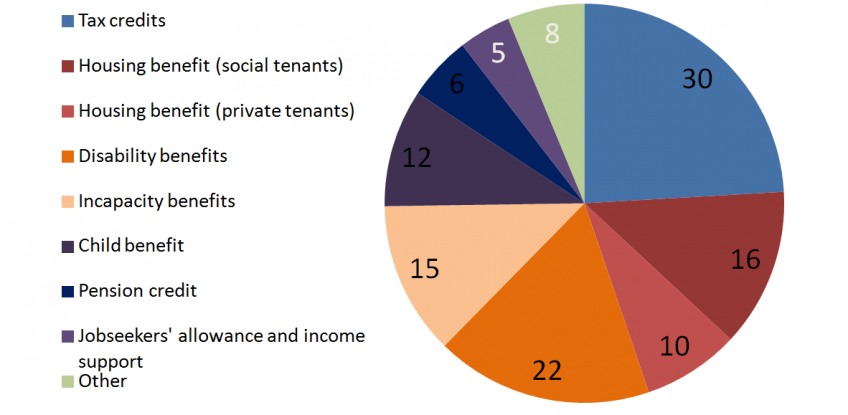

That leaves another £10½bn of cuts to annual benefits spending that we are yet to hear about. This fiscal year, spending on benefits and tax credits is expected to total about £220 billion. The Conservative manifesto pledged to exclude more than 40% of that budget from cuts: it committed to protecting state pensions (and in fact to maintain the ‘triple lock’ on the basic state pension) and universal pensioner benefits, which account for £95bn of annual spending. This almost doubles the proportionate cut implied for the rest of the budget, to about 10%. The chart below breaks down the £125 billion of annual spending that is left unprotected.

Benefit and tax credit spending not explicitly protected by Conservatives, £ billion, 2015-16

Source: DWP benefit expenditure tables; OBR Economic and Fiscal Outlook.

The biggest items are tax credits (£30bn) and housing benefit (£26bn). Together they account for almost half of the unprotected spending. Disability and incapacity benefits between them account for almost a further third. Child benefit is the next largest. Some combination of those benefits are virtually certain to be cut if £12bn of cuts by 2017–18 are to be delivered.

What kinds of people are likely to be affected? That of course depends on the detail. But we can identify some broad likely patterns. Because of the protections outlined above, about 80% of entitlements to the benefits in the chart go to working-age families; and because the large majority of working-age benefits spending is means-tested, it would be very difficult to avoid hitting low-income households – particularly those with children – hardest: three quarters of entitlements to the benefits in the chart go to families in the bottom half of the income distribution, of which more than half go to families with children.

Specific options

In order to provide a sense of scale and of the kinds of families that could be affected, below we discuss some illustrative options for cutting working-age benefit spending. There are many more possibilities not discussed here, some of which were discussed in a previous observation looking at hypothetical options leaked to the BBC, and others of which were discussed in a chapter of February’s IFS Green Budget.

Some of the options below would of course affect overlapping groups of people. Hence, although we discuss the options in turn, the most significant impacts on family incomes will often be found where more than one cut bites at once. For example, low-income renting families could be affected by cuts to housing benefit and tax credits simultaneously, just as in the package of welfare cuts introduced by the coalition government. It is important that any package is designed coherently in view of its combined effects. Note also that some of these policies would interact with each other, in a way that means one cannot simply add up the revenue from each of them individually to arrive at a cumulative figure. For example, if you cut child benefit for large families, there is then less scope to make savings from means-testing it more aggressively.

Benefits for families with children

From January 2013, the previously-universal child benefit was tapered away from families containing an individual with a taxable income over £50,000 and removed completely for families containing an individual with a taxable income above £60,000. This meant that about 15% of families with children effectively lost some entitlement to child benefit, and about 10% lost all of it. Because (absurdly) these thresholds are fixed in cash terms over time, fiscal drag is set to double the number of families losing some or all of their child benefit over the next decade, to 2.5 million.

A way of making quick and significant cuts without affecting the entitlements of the very poorest is to take child benefit away from more families now, rather than allowing it to happen gradually and arbitrarily through fiscal drag. One could abolish child benefit per se and simply increase the child element of child tax credit (and its imminent replacement, universal credit) correspondingly, so as to compensate low-income families who claim their means-tested entitlements. This would have advantages: it would integrate the two systems of income-related support for children, rather than maintaining two systems operating in completely different ways; and it would signal the end of some undesirable features of the current child benefit charge (discussed here).It would be a big cut, meaning that the majority of families with children would lose at least £1,000 per year, with only the entitlements of approximately the lowest-income third protected. As a result it would reduce spending significantly, by around £5bn. The expansion of means-testing would come at the usual costs for work incentives and potential hassle and stigma for claimants. One could of course design a policy to extend the means-testing of child benefit less aggressively than this (affecting fewer families and saving less money).

Alternatively, one could cut tax credits and take money away from a lower-income group of families. This would reverse some of the large increases in generosity towards this group over recent history. Returning the per-child element of child tax credit to its real (CPI-adjusted) 2003–04 level would reduce entitlements for about 3.7 million low-income families with children by an average of £1,400 per year, and would cut spending by about £5bn. For the poorest families it would mean a takeaway of £845 per child per year. Taking as an example a 2-child family where at least one parent works full-time, it would mean tax credit entitlement running out at £28,847 of gross earnings rather than £32,969.We estimate that this would increase relative child poverty by about 300,000 (or 2.5 percentage points) so, in the absence of much-needed clarity from the government on its child poverty strategy (and in particular its attitude towards the supposedly legally-binding 2020 child poverty targets) it is difficult to assess the coherence of such a policy. While about two thirds of families with children on tax credits are in work, like most cuts to means-tested benefits this policy would tend to strengthen work incentives – families would have less tax credit income to lose by increasing their earnings or to gain by reducing their earnings.

A more across-the-board cut, which featured in a document leaked to the Guardian Newspaper prior to the election, would be to reduce the amount of child benefit payable for the first child in the family by £7 per week, so that it is the same as the amount payable for subsequent children (£13.70). This would save £2.5 billion per year and would mean a flat cash-terms cut in generosity (of about £360 per year) for all families receiving child benefit.

A cut with a different distributional impact would be to abolish the amounts payable in respect of third and subsequent children. If this just applied to child benefit it would reduce spending by about £1 billion per year. Extending the same principle to means-tested support for children one would increase this sum by a further £3bn per year. However, such a policy might apply only to new births or conceptions, in which case the full saving would not be realised until the 2030s, making this of little relevance for the 2017–18 target. Losses from these cuts would be particularly concentrated towards the bottom of the income distribution: large families are more likely to be poor. Together with the fact that each losing family contains at least three children, this would again sit uneasily alongside any desire to reduce income poverty among children.

Housing benefit

The coalition government made cuts to the generosity of housing benefit totalling about £2 billion per year – though underlying trends (rising private rents relative to earnings and the growth of the private rented sector) meant that real housing benefit spending was still £1 billion higher in 2015–16 than in 2010–11. Given the scale of housing benefit, it is likely to be considered as part of any £12bn package of further cuts. As with the housing benefit cuts made in the previous parliament, further cuts may be accompanied by some additional funding for the protection of particularly vulnerable claimants, which could slightly reduce the net saving.

Cuts to housing benefit unsurprisingly tend to affect low-income families – and hence again to increase income poverty - and particularly those with high rents. They can have behavioural impacts too. There is evidence that the package of cuts to housing benefit in the previous parliament resulted in a small proportion of claimants renting cheaper types of properties; and cuts to housing benefit tend to strengthen work incentives – they mean that families have less housing benefit to lose by increasing their earnings or to gain by reducing their earnings. It is worth noting, though, that cuts to housing benefit may affect substantial numbers of in-work families. The proportion of housing benefit claimants who are in work has been rising quickly, and is now about one fifth (1.1 million).

Most of the coalition’s cuts to housing benefit were in the private rented sector, which actually accounts for only 40% of housing benefit spending. Perhaps the most obvious way to reduce generosity here is to lower the maximum amount of rent that housing benefit will cover (known as the Local Housing Allowance (LHA) rate). The coalition reduced LHA rates from the 50th percentile to the 30th percentile of rents in the local area. Early evidence suggests that this had little effect in pushing down rents, and hence resulted in most claimants paying more net rent, with a small proportion responding by moving house. We estimate that a further reduction in LHA rates to the 20th percentile of local rents would reduce spending by roughly £400 million a year, with 1.5 million low-income private renters having their entitlements reduced by an average of around £300 a year. Because LHA rates are set separately by area and family type, families whose rents are particularly low relative to other families of the same structure living in the same area would not be affected.

An alternative to reducing LHA rates is to make all claimants pay some share of the rent. This would give all tenants some incentive to shop around for cheaper housing. Introducing a ‘co-payment’ of 10% (i.e. reducing housing benefit awards from 100% to 90% of rent up to the LHA rate) for private sector tenants would cut spending by about £0.9bn.

Any attempt to cut housing benefit spending substantially may well involve reforms affecting social tenants, as they account for the majority of such spending. Despite the so-called ‘bedroom tax’, most social housing tenants on housing benefit currently pay no net rent (i.e. their housing benefit covers all rent), subject to a means test. Introducing a new 10% co-payment for all social tenants (and reducing housing benefit by a further 10% for those already affected by the ‘bedroom tax’) would cut spending by about £1.6bn.

Whether in the private or social sectors, co-payments specified as a percentage of rent would mean that those with higher rents – including London renters and larger families - would tend to lose most in cash terms. However, even those with the lowest rents would be affected (unlike with reducing LHA rates, for example).

As discussed above, the Conservatives have already committed to removing housing benefit entirely from 18-21 year-olds on Jobseeker’s Allowance, reducing spending by £0.1bn. One could go further: abolishing housing benefit for all aged under 25 would reduce spending by a further £1.5bn. This would be a big cut for the 300,000 affected claimants, averaging about £5,000 per year. Exempting those with dependent children – perhaps because they can less reasonably be expected to live with their parents – would roughly halve the saving.

Disability, incapacity and carers’ benefits

Substantial amounts are spent on benefits for those with disabilities and those who care for them. With the exception of Employment and Support Allowance, these benefits are not means-tested. Hence there is more scope here than elsewhere to protect low-income families from cuts. But of course the lack of means-testing in this area of the system reflects the fact that these benefits are there to compensate for the additional costs of disability. There is evidence that, as one might expect, disability is associated with a higher level of material deprivation than income alone would suggest (though income poverty too is higher in families where someone is disabled).

If the government went down this route, then taxing universal disability benefits (and hence treating them like most other non-income-related benefits) would be one natural option (though technically a tax rise rather than a benefit cut). Those with incomes below the personal income tax allowance would, of course, not be affected. Taxing Disability Living Allowance and its replacement, Personal Independent Payments, would boost revenues by £0.9 bn. Taxing Attendance Allowance (which goes to pensioners only) as well would increase revenues by a further £0.6bn.

If the government wanted to cut benefits for higher-income recipients of Carer’s Allowance – a benefit for full-time carers – it could simply abolish it, as apparently in a menu of options drawn up by civil servants and leaked to the BBC last month. Those with low enough incomes – most recipients of CA, in fact – would be able to claim additional means-tested benefits instead. The BBC report suggested a net saving of about £1bn per year.

Conclusions

The government wants to find £12bn per year of further cuts to benefits – mostly or entirely from the working-age portion of the budget – and to do this by 2017-18. This will involve difficult decisions. In many ways it provides an illustrative case study of the issues that governments always face when looking for ways to reduce spending in this area. Saving money while only affecting better-off claimants will tend to weaken work incentives. Saving money while protecting or strengthening work incentives tends to mean hitting some of the poorest in society and hence increasing poverty. We should soon find out the balance that the new government chooses to strike.