Key findings

1. The UK’s recent experience is an extreme example of a global shift in macroeconomic volatility from demand to supply. The UK has suffered two major shocks since 2020. The rebound from the pandemic proved to be quick, but incomplete. The subsequent terms-of-trade shock through 2022 has meant a further slowdown. Recent ONS statistical revisions paint a rosier picture of the past. But even so, UK GDP is still 5.2% short of its 2012–19 trend: a worse relative performance than either the United States or the Euro Area where the shortfalls range between 2% and 3%. Upwards revisions to the UK’s estimated post-pandemic performance, while good news, also do not translate into an improved outlook ahead.

2. From here, the UK economic outlook hinges on three primary factors: first, the boost associated with the unwinding of the adverse terms-of-trade shock; second, the headwind associated with tighter monetary policy; and third, the potential for greater inflationary persistence – especially in wage setting. The first has supported growth consistently over the past 12 months as news around the terms-of-trade shock (especially around energy prices) has turned out better, and fiscal support has remained in place. However, many of these supports now seem to be fading. And monetary policy is likely to weigh heavily over the economic outlook. Our estimates suggest that the 5.15 percentage point increase in Bank Rate might be expected to eventually reduce output relative to where it otherwise might have been by roughly 4.0–4.5 percentage points over two to three years. Credit growth has, in recent months, dropped to levels only previously observed during the post-GFC Credit Crunch, in a sign of the economic shock to come.

3. Even before the shock to credit, firms and households faced a continued squeeze. The weakness of UK corporate margins to this point has been genuinely exceptional. Unlike in the US and the Euro Area, changes in firm profit margins have made only a minimal contribution to the rate of overall inflation and wages proportionately more. Our best estimate of firms’ bottom lines suggests that profitability remains around 3 percentage points down on pre-COVID levels. A key question for the outlook now is whether firms seek to keep prices higher as costs fall in order to repair margins or cut back on staff. We think it unlikely households will be able to come to firms’ rescue. Even with modestly positive real wage growth, real household disposable income is likely to continue to shrink in 2024 as a result of higher interest rates and ongoing tax rises. We expect household consumption to stagnate through both 2024 and 2025.

4. Household and corporate balance sheets are no stronger in aggregate than they were pre-pandemic. While households in particular enjoyed a marked boost in net worth through 2020, in the years since, the value of both financial and housing wealth has been eroded by the surge in inflation. The implication is that net worth within the household and non-financial corporate sector is now 33 percentage points smaller as a share of total output than in 2019 (whereas it is well above pre-pandemic levels in the US). An older working population now means households are more resilient to the cash-flow effects of higher interest rates, but more vulnerable to changes in asset prices. Already, savings are rising rapidly in response to the recent balance sheet deterioration. This adds to the downside risks, with the potential for an adverse feedback effect between asset prices, demand and employment.

5. There are signs labour market dynamics are starting to shift. Unemployment has increased from 3.5% in the 2022 trough to 4.3% now. We expect an increase to 5.8% by the end of 2024. Through 2022, labour demand was particularly strong while labour supply was weak. There are signs that supply is beginning to normalise – with improvements in matching and increases in aggregate labour supply. On the demand side, there are also clearer signs that softening activity is feeding into vacancies – with most remaining demand strength now concentrated in the public sector. There are also tentative signs that some labour hoarding is beginning to ease. With the UK already close to the historical threshold at which unemployment begins to feed back into consumer confidence and demand, we see growing risks that higher unemployment (alongside higher rates) feeds back into a broader weakening in household consumption.

6. We expect a reduction in CPI inflation from 6.7% in August to a little over 4% by the end of the year – which would mean the Prime Minister meets his goal to halve inflation. None of this should be taken as a sign of complacency with respect to the inflationary risks, however. The focus now is more how far price growth can fall back through 2024 – i.e. whether inflation makes it from 4% to 2%, and whether it does so sustainably. Here the key question in our view is whether pass-through of adverse cost shocks proves symmetrical over the coming months. If so, then the scope for firms to recover margins will be limited, and prices should fall both quickly and completely. A slower reduction in inflation would create space for more near-term resilience, but also more persistent price and wage growth. This could mean more rate rises, and plausibly a longer recession later on.

7. The risks of a more disruptive inflationary scenario are very real. But from here, these appear most likely to relate to any further fiscal policy errors. If there were to be any ill-timed fiscal giveaways, they would risk shifting the UK into a higher-inflation paradigm. Any near-term fiscal boost (e.g. in the form of pre-election tax cuts) could therefore require repayment many times over, not just in higher taxation but through a protracted monetary-policy-induced recession. The UK has little room for ill-timed fiscal inducements.

8. While the risks around inflation are increasingly skewed to the upside, the risks around activity look skewed to the downside, especially in the medium term. In part this reflects the potential for more embedded inflation. It also reflects the possibility of a more meaningful adverse effect from weaker private sector balance sheets. Having delivered the sharpest monetary tightening since the early 1980s, we are in uncharted territory in terms of the potential economic spillovers. Fewer households have substantial outstanding mortgages. But more are reliant on private savings and housing wealth for their retirement. This transmission mechanism is more unpredictable, especially when global rates could remain higher.

9. This leaves monetary policymakers with a conundrum. The risk of embedded inflation means that slowing growth and higher unemployment may be insufficient for a loosening of monetary policy; instead, policymakers may want to wait to see firm evidence of disinflation. The issue is that, by definition, once this is achieved, policy has been too tight for too long. In current circumstances, that is also risky – with the economic sensitivity to weaker asset prices likely greater, but also very difficult to reverse. The historical lesson since the 1970s has been not to cut rates until one is sure the inflationary risks have been contained. But a higher level of indebtedness means the policy trade-offs are now harder to navigate, and the balance of risks is more two-sided.

10. The economic experience of the last three years is a harbinger of the kinds of supply shocks that are likely to come. In our view, an over-reliance on monetary policy has meant poorer policy trade-offs and a weaker overall recovery – especially when fiscal policy has remained extraordinarily loose. Long lags mean rate hikes offer only limited insurance, and often at great (and persistent) cost. And their blunt nature reduces the potential for a more investment-friendly recovery, while also adding to the financial stability risks. The economic challenges of the coming decades are hard enough without persistent policy headwinds. In our view, the policy mix needs to change. We think there is a strong argument for fiscal policy to take on more of the burden of managing the risks around inflation. This should come alongside efforts to invest in greater structural flexibility. As things stand, the UK is poorly placed.

Introduction

Recent British economic experience has been an exhibit in the shift from a demand-driven economic world to one defined by weak, volatile supply. While recent shocks look to have eased, adjustment remains far from complete. And these challenges sit alongside legacy issues of poor productivity, falling business dynamism and high debt – all of which limit the UK’s room for manoeuvre. To put it bluntly – the UK is a small open economy beset by chronic structural challenges and acute adjustment-related exigencies. In this chapter, we aim to tease out the impact of these respective shocks, discuss their likely development and set out their implications for the economic and policy outlook.

The starting point here is one of exceptional macroeconomic volatility. The UK has effectively suffered two distinct, if related, ‘recessions’ since 2020. The rebound from the pandemic proved quick, but incomplete – even in light of recent revisions. The subsequent terms-of-trade shock through 2022, while not generating two consecutive negative quarters of GDP growth, has meant a further distinct slowdown. Slow domestic reallocation – in part because of what, in retrospect, was an over-reliance on fiscal subsidies – has compounded the associated hit to supply. The net implication has been to push inflation higher, while the labour market has ground tighter. Monetary policy has subsequently been forced to tighten significantly.

The outlook from here is, in our view, a three-way tussle between: (1) the boost from the unwind of the adverse terms-of-trade shock; (2) the headwind associated with tighter policy; and (3) the potential for greater inflationary persistence – especially in wages.

The terms-of-trade shock, as we discussed last year, has been the predominant macroeconomic driver over the past 12 months. Having worsened considerably through 2022, energy prices have since fallen significantly. Alongside persistent fiscal support, the external picture for the UK private sector has subsequently improved. Activity has surprised to the upside as a result. Many of these effects now appear to have run their course, however, with further improvements likely to be offset by the unwind of associated fiscal support. The first-order impact of the terms-of-trade improvement seems insufficient, at least alone, to return firms and households to a position of economic stability. Instead, firms in particular still likely face a struggle to restore profitability.

In our view, the UK therefore still faces a challenging adjustment ahead. We view two scenarios as broadly plausible:

- First, firms could repair profit margins through elevated price growth. This could then enable a period of near-term economic resilience where the labour market remains tight and wage growth elevated. However, this would suggest more persistent inflation, higher rates and – plausibly – a more severe downturn later.

- Second, firms could repair profit margins by cutting back on capacity and cost pressures – especially workers and wages. This would suggest a relatively sharp reduction in wage pressures, weaker real incomes and – plausibly – a larger initial increase in unemployment.

We lean towards the latter scenario. As we discuss below, pricing power has been patchy throughout recent shocks. And as costs have been falling, this so far seems to be feeding through symmetrically into lower price growth – limiting scope for a recovery in corporate margins. This could of course shift. But even with modestly positive real wage growth, household disposable income is likely to continue to shrink as higher mortgage costs continue to feed through. This reflects transmission from a generational monetary policy tightening that is only now beginning to build. This suggests a narrowing path to a recovery of pricing power, and with it more persistent inflationary pressure.

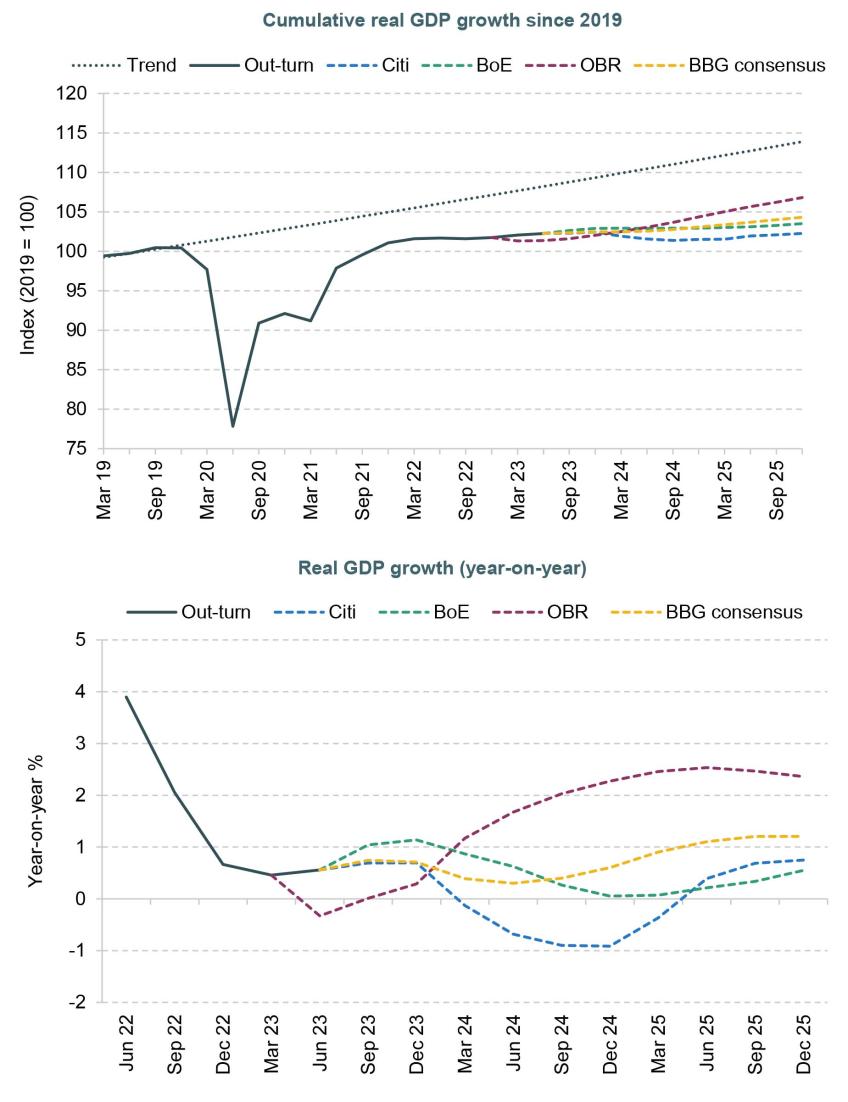

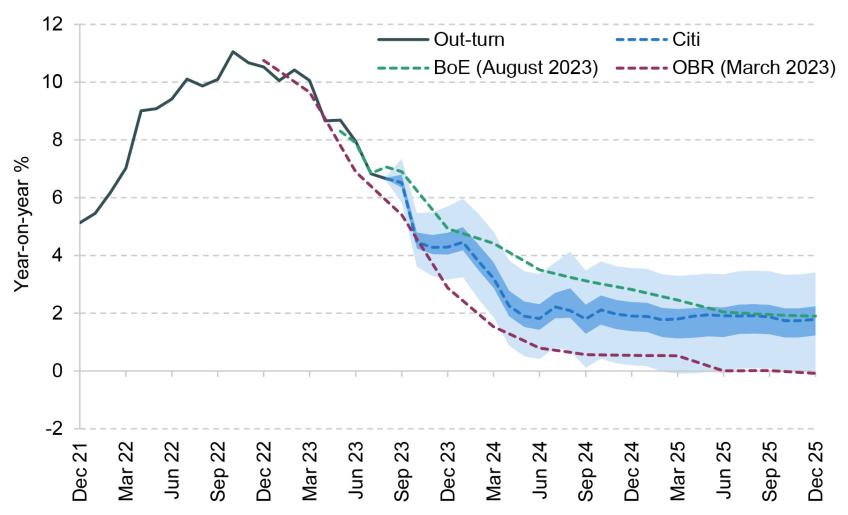

Instead, we expect weak margins and policy headwinds to drive a moderate recession through the first half of 2024. We expect GDP will fall 0.7% by next year, followed by growth of 0.4% in 2025. This is more pessimistic than the Office for Budget Responsibility’s forecasts from March – which suggest cumulative growth of 1.6% over 2023 and 2024 – and Bank of England forecasts that suggest growth of 1.1% over the same period (Figure 2.1). We forecast that unemployment will increase relatively quickly to a 5.5–6.0% range by the end of 2024, up from 4.3% now and a trough of 3.5% in 2022, feeding back into a more persistent economic softening. We expect CPI inflation to fall to a little above 4% by year-end 2023 to a little below the 2% target in Q2 2024 (Figure 2.2), well below current Bank of England expectations but closer to economists’ consensus.

Uncertainty here remains elevated. For economic activity, we see the risks as broadly balanced in the near term but skewed to the downside further out. As we noted above, a slower fading of inflationary pressures and stronger near-term growth remains a plausible, temporary equilibrium. But this would likely drive further interest rate increases, risking a protracted recession later on. On the other hand, having delivered the sharpest monetary tightening since the early 1980s, we are in uncharted territory in terms of the potential economic spillovers. With household and corporate balance sheets no stronger in aggregate than they were pre-pandemic, both already appear in a nascent process of balance sheet repair.

Figure 2.1. Forecasts for UK real GDP growth

Note: Official forecasts are indexed to latest available data for the last realised quarter at the time of the forecast. For the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR), these data are the March forecast and are therefore indexed to Q4 2022. Bank of England (BoE) forecasts show August forecasts indexed to the latest data for Q2. BBG shows the consensus of private forecasters surveyed by Bloomberg. ‘Trend’ is based on average growth between 2012 and 2019.

Source: ONS, Bloomberg LLP, Bank of England and OBR.

Figure 2.2. Forecasts for UK CPI inflation

Note: The shaded areas show the probability distribution around the in-house Citi forecast, with the darker shaded area denoting the range between the 40th and 60th percentiles of an adjusted, discretionary normal distribution around the core forecast. The lighter shaded area shows the range between the 20th and 80th percentiles of the distribution. The BoE forecast is the mean estimate from the August Monetary Policy Report. The OBR forecast is taken from the March Economic and Fiscal Outlook.

Source: ONS, OBR, Bank of England and Citi Research.

The external context matters here. With US rates likely to remain higher for longer (see Chapter 1), this risks further cramping fiscal space. This also adds to the downside risks around asset prices – with changes here driven not just by spot policy rates, but by the broader matrix of financial conditions. In a small open economy, these are only partially in the gift of domestic policymakers.1

With respect to inflation, the risks to our forecasts remain skewed to the upside in both the short and medium term. In the former case, this primarily reflects continued risks associated with commodity prices and the currency. In the latter case, it reflects the continued risk of a shift in domestic wage and price setting. These risks remain material, but they are perhaps not as large as they were at the start of 2023. And the counterbalancing effects associated with a more persistent downturn are also becoming more prominent.

With a long campaign for the next general election now in its initial stages, our analysis points to two important takeaways.

First, in the near term, the UK economy remains stuck between weak growth but continued inflationary risks. Constraints in the latter case mean that if there were to be any ill-timed fiscal giveaways, they would risk shifting the UK into a higher inflation paradigm. Pre-election tax cuts may therefore require repayment many times over, not just in higher taxation but through a protracted monetary-policy-induced recession. The UK has little room for expedient fiscal inducements.

Second, the case for meaningful structural reform is increasingly urgent. The UK is once again exiting a major international shock towards the back of the pack. With big ecological and geopolitical challenges, the UK needs to build an economy capable of rapid reallocation. This will require a newfound and successful focus on macroeconomic resilience, as well as a policy playbook that encourages reconfiguration, rather than stands against it. After 15 years of stagnation, the sooner this happens the better.

Below, we begin by discussing the post-pandemic recovery (Section 2.2). We then move to discuss the outlook – with a particular focus on the impact of higher interest rates for both households and firms (Section 2.3). We then discuss the outlook for UK supply and the labour market, before turning to wages and inflation (Section 2.4). We conclude in Section 2.5 with some comments on the implications for monetary and fiscal policy.