Executive summary

The special educational needs and disabilities (SEND) system in England has faced unprecedented pressure over the past decade, and without substantial reform it will likely become unmanageable for local authorities over the coming years. Fundamentally, this is due to the rocketing number of children and young people with education, health and care plans (EHCPs). Children with EHCPs are those with the highest needs and local authorities are statutorily obligated to cover the costs of provision set out in EHCPs. The reasons behind this rise in EHCPs are complex, but potential explanations include increased severity of needs, expanded recognition and diagnosis of needs, and stronger incentives to seek statutory provision.

Key findings

1. The number of school pupils with EHCPs has risen by 180,000 or 71% between 2018 and 2024. As a result, nearly 5% of pupils now have EHCPs. This rise in pupils with EHCPs has been driven by three specific types of needs: autistic spectrum disorder (ASD); social, emotional and mental health needs (including ADHD); and speech, language and communication needs. The rises in ASD, ADHD and mental health needs appear to be global phenomena across high-income countries.

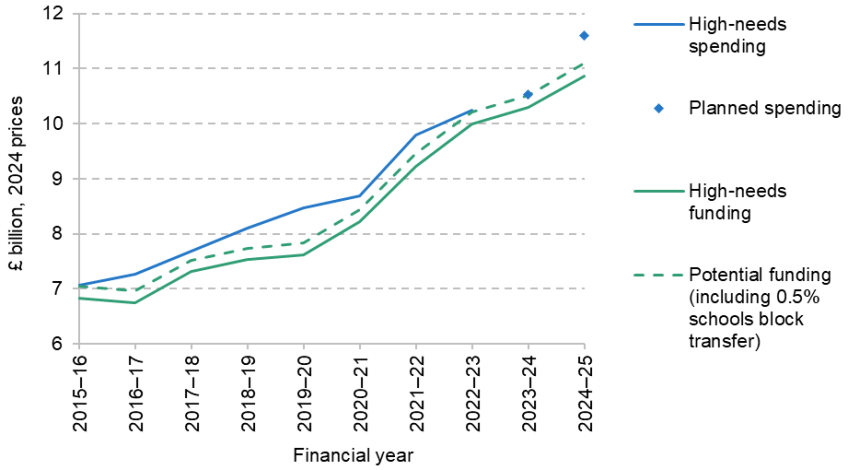

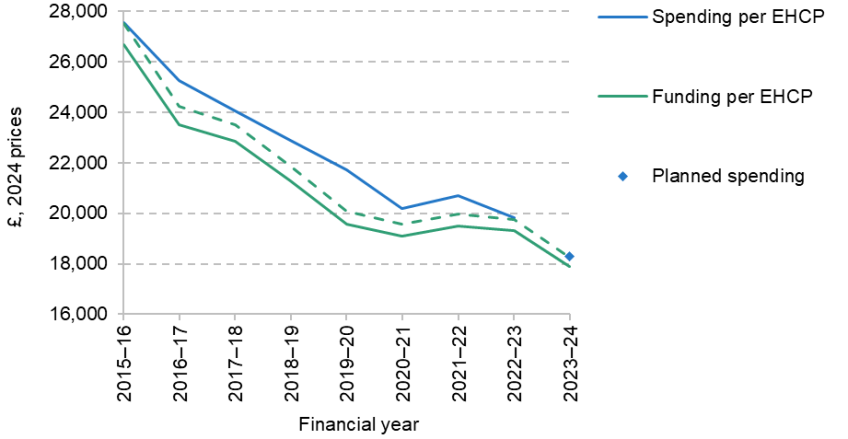

2. Central government funding for high needs currently totals nearly £11 billion and has increased substantially, with a 59% or £4 billion real-terms rise between 2015–16 and 2024–25. This growth can account for about half of the total real-terms rise in school funding over the same period. However, even with this substantial rise, funding has not kept pace with the increase in pupils with EHCPs. As a result, per-EHCP funding has fallen by around a third in real terms over this period.

3. High needs spending has been consistently higher than funding by £200–800 million per year between 2018 and 2022, mainly because local authorities have a statutory obligation to deliver the provision set out in EHCPs. As a result, local authorities have accumulated large deficits in their high-needs budgets, estimated to be at least £3.3 billion in total by this year. An accounting fudge known as the ‘statutory override’ has kept these deficits off local authorities’ balance sheets and prevented many from having to declare bankruptcy. This short-term fix is currently due to end in March 2026.

4. There are large variations in identified need, funding and deficits across local authorities. Some areas see much higher proportions of pupils with SEND or EHCPs which seem partly due to differences in identification practices. High-needs funding also varies significantly across areas, with some of the largest deficits seen in places with lower levels of per-EHCP funding. This emphasises the need for reform of the funding system to better align with current need, as well as a more uniform approach to SEND identification and support to avoid a ‘postcode lottery’ in provision.

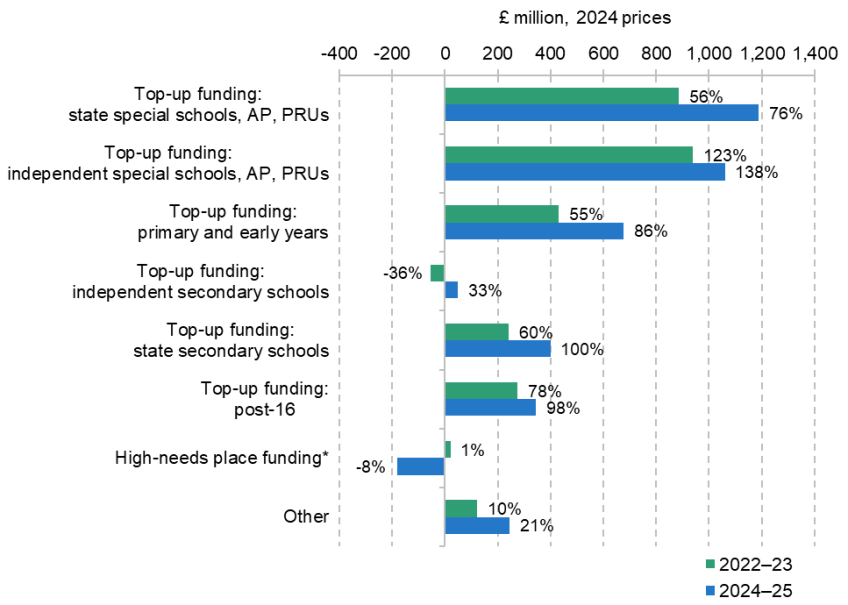

5. Nearly two-thirds of the increase in spending has been driven by increased spending on pupils in special schools, with a £900 million increase in top-ups for state-funded special schools and a £900 million rise in spending on fees for pupils in independent special schools between 2015–16 and 2022–23. The latter accounts for very few pupils (30,000 in total), but placements are extremely high-cost in independent special schools (£61,500 per year) compared with the state-funded sector (£23,900). Local authorities have probably had to rely on such provision due to capacity constraints in state-funded special schools and a lack of effective provision in mainstream schools.

6. There are financial incentives for schools to seek EHCPs. Mainstream schools can only access local authority ‘top-up’ funding if the additional cost of SEND support is over £6,000 (the first £6,000 must be covered from core school budgets). This can only really be achieved with an EHCP. This £6,000 threshold has not been updated with inflation for over 10 years, eroding its value in real terms and therefore bringing more pupils into the group who require top-up funding and, by extension, EHCPs. A tight picture on core school spending and rising demand for SEND support have also made it harder for schools to fund provision from core budgets.

7. The government’s own forecasts suggest annual spending on high needs will rise by at least £2–3 billion between 2024–25 and 2027–28, which largely reflects projected increases in EHCPs and need over the next few years. Even with the additional £1 billion announced in the 2024 Autumn Budget, these increases in spending would imply cumulative local authority deficits of over £8 billion by 2027 assuming high-needs funding is held constant in real terms. Given the statutory obligations attached to EHCPs, this should be the default assumption for the public finances.

8. Meaningful reform will be complex and costly. It is likely to require a significant expansion of the core SEND provision available in mainstream schools, an expansion of state-funded special school places, a geographic redistribution of funding, and maybe reducing the statutory obligations currently attached to EHCPs. At the moment, there are huge delays in getting assessments, forcing many parents to get private assessments or go to legal tribunals. Building parental confidence in a new system will therefore be challenging. Any transition to a new system would also be costly as it would likely entail some double funding to cover current obligations. Although difficult, substantial reform is necessary to create a financially sustainable and equitable SEND system. The default is spending an extra £2–3 billion per year on an unreformed system by 2027–28.

1. Introduction

Children and young people are determined as having special educational needs or disabilities (SEND) if they have a learning difficulty or disability that requires them to be given special educational provision (Department for Education and Department of Health, 2014). This is a very wide definition, encompassing specific learning difficulties, physical disabilities, neurodivergence and mental health problems. Identification of SEND generally takes place within schools or early years establishments and, as such, can be dependent on the resources and practices of individual establishments.

Schools are primarily responsible for meeting the educational needs of their pupils with SEND. For those that require more specialist support than core school SEND provision can cover, an education, health and care plan (EHCP) can be sought by the child’s parent/guardian or school. EHCPs (introduced as part of the 2014 Children and Families Act) set out the tailored education, health and care support that a child requires and that the local authority is obligated to provide for them. They are drawn up by local authorities after a child or young person is deemed to need one following an EHC needs assessment, although there is no clear or consistent threshold of need to qualify for an EHCP. Getting an assessment can also be a difficult process, often involving huge delays, and with many parents taking legal action against local authorities’ decisions not to undertake assessments.1 Some pupils with very high needs are educated outside of mainstream provision in special schools, which can provide more tailored educational provision including for specific types of high need.

Core schools funding comes from the Dedicated Schools Grant (DSG) which is set centrally and allocated to local authorities through the National Funding Formula (NFF). Within the DSG, there are ring-fenced ‘blocks’, including one for high needs, which are intended to control how local authorities allocate money across services. All schools receive a notional SEND allocation, which is an identified element within schools’ budgets that is expected to be used to cover low-cost, high-incidence SEND and as a contribution to the costs of pupils with higher needs.

Since 2014, mainstream schools have been formally required to cover up to the first £6,000 in additional costs (above basic per-pupil funding) of supporting pupils with SEND from their core schools budget (Department for Education, 2012 and 2013)2. By contrast, state-funded special schools and SEN units within mainstream schools receive £10,000 of funding per place, which is funded by the DSG high-needs block. If educational establishments have pupils with EHCPs who require funding above these thresholds, they can apply for ‘top-up’ funding from the high-needs block to meet these costs. These monetary amounts have not been uprated with inflation since being first introduced as guidelines in 2013. Additional high-needs funding comes from other grants, the Education and Skills Funding Agency (ESFA), and grants to cover the cost of pay awards to special school teachers, among other sources.

Prior to these reforms, pupils with SEND could access tailored provision by getting a ‘statement of SEN’. Schools were also expected to cover the initial costs of SEN statements from their core budgets. The £6,000 and £10,000 thresholds introduced in the 2013 reforms did not really change this, but it did formalise the process in a consistent way. High-needs pupils without statements of SEN were covered by the ‘School Action’ and ‘School Action Plus’ programmes, which were meant to coincide with lower-cost, high-incidence needs and were expected to be covered by notional SEN budgets. This is broadly still the case in the current system for pupils with SEND but not EHCPs.

The more significant changes related to the age groups covered and school choice. There was a substantial change to the scope of eligible pupils: statements of SEN only covered pupils aged 5–18 in schools, whereas EHCPs can cover young people up to 25, young people aged 16–18 in colleges and children aged under 5 in early years settings. Furthermore, parents gained more rights to request a place in a special school, in either the state-funded or independent sector.

There have also been significant changes to the way in which the SEND system is funded since 2013. Prior to 2013, all school funding came via a single DSG allocation and local authorities had considerable discretion over how much to spend on high-needs provision and how to allocate this funding. Since 2013, the DSG has been broken up into notional blocks, one of which is dedicated to high needs. In 2014, the £10,000 thresholds for place funding in special schools and initial mainstream school expenditure before top-up funding could be accessed were applied nationally (Department for Education, 2013). Previously, local authorities could control how high-needs funding was allocated to schools – for instance, by providing more funding up front rather than setting a £6,000 threshold for what mainstream schools had to contribute. Since the introduction of the NFF in 2018, the DSG schools block has been ring-fenced, with transfers to other blocks highly restricted. The use of historical spending patterns as a factor in the 2018 high-needs NFF also helped to cement geographical inequalities in high-needs funding that had arisen over time. As a result of these reforms, local authorities now have much less flexibility over both the level of high-needs funding and the mechanism by which it is allocated across pupils and schools. Over the same period, we have seen significant squeezes on core school budgets, which might have limited schools’ ability to contribute to core SEND provision and increased incentives to apply for EHCPs.

The SEND system has become financially unsustainable over recent years. The number of pupils with SEND, and in particular those with EHCPs, has rocketed since around 2018. As local authorities have a statutory obligation to provide the support set out in each EHCP, but funding has not kept pace with this rise, many face huge deficits in their high-needs budgets (National Audit Office, 2024). For those navigating the system, the increased demand has led to significant backlogs in EHC assessments, and access has become more combative (Isos Partnership, 2024).

In response, governments have significantly increased funding in recent years. Indeed, between 2015 and 2024, the past government increased DSG high-needs block funding from £6.8 billion to £10.4 billion, a rise which took up nearly half of the £7.6 billion increase in total school funding (all in 2024 prices; Sibieta, 2024). In the October 2024 Budget, the new government further increased high-needs funding by £1 billion. However, these funding rises have not always been sufficient to close in-year deficits, let alone pay down the accumulated high-needs debts. The previous government set out an improvement plan for the SEND system in 2023 which included goals for a new national system and national standards (Department for Education, 2023). Since the election of the new government, it is uncertain whether this plan will go ahead, but ministers have reiterated the need for reform and stressed goals such as improving inclusion in mainstream schools.

In this report, we give an overview of the current crisis in the SEND system and weigh up potential reforms. We first look at how demand for SEND provision has evolved, including how pressures vary across different needs, schools and areas. We then look at how this has translated into strains on councils’ high-needs budgets, and where costs have risen most. Finally, we discuss potential types of policy response. Ultimately, without significant changes to how the system is run and financed or to the demands placed on local authorities, it is hard to see how these system-wide pressures can be sustainably resolved.

2. Rapid rises in numbers of children with SEND

The number and share of pupils with SEND have changed dramatically since 2000. In this section, we explore how numbers have changed across different types of provision and need, and analyse the different impacts this has had across schools and areas. As discussed in recent reports by the National Audit Office (2024) and Isos Partnership (2024), the reasons behind these changes are complex but likely include financial incentives to seek EHCPs in the new system, developments in recognising and identifying existing needs, and underlying factors pushing up needs, some of which can be seen across all high-income countries, particularly with regards to mental health and autistic spectrum disorders.

Overall numbers

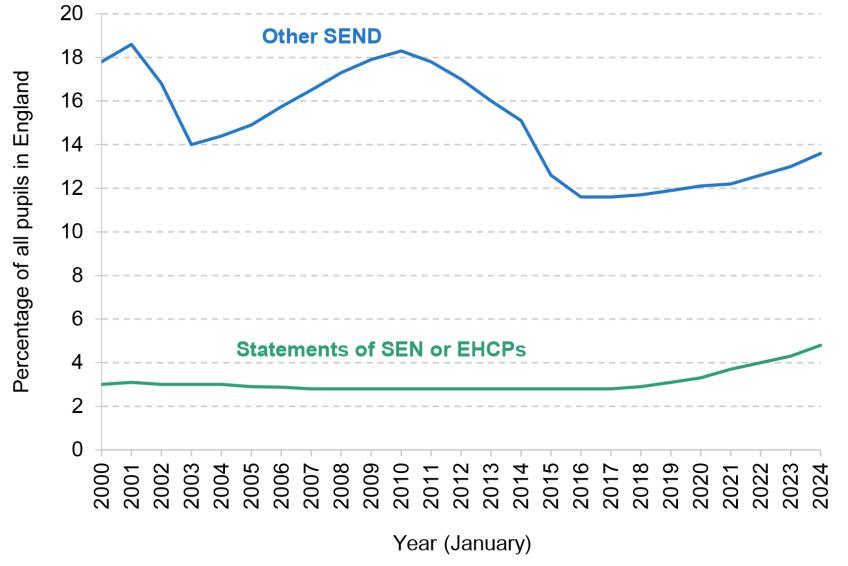

Since 2000, the share of pupils with some form of SEND has fluctuated significantly (Figure 1). This is in part influenced by the nature of the SEND system in place. For instance, reforms to the system in 2003 and 2014 can partly account for the sharp drop in non-statemented SEN (low-cost, high-incidence needs) in these years, and the coalition government’s aim of reducing ‘over-identification’ of SEND (Department for Education, 2011) seems to account for some of the drop in non-statemented SEN from 2010. By contrast, rates of specialist statutory provision in the form of statements of SEN or EHCPs remained broadly stable at around 2.9% of total pupils between 2000 and 2018. This rate has changed significantly in recent years, with the share of pupils with EHCPs rising to 4.8% in 2024 and absolute numbers increasing by 71% from 253,679 in 2018 to 434,354 in 2024. This rise looks set to continue at least over the short term as requests for assessment and waiting times to receive them remain high.

Figure 1. Share of all pupils with different levels of SEND over time

Note and source: Includes pupils in nursery, primary, secondary, special and independent schools. ‘Other SEND’ includes School Action and School Action Plus. Figures for 2000 to 2002 are taken from Department for Education and Skills, Special educational needs in England January 2004. Figures for 2003 to 2006 are taken from Department for Education and Skills, Special educational needs in England: January 2007. Figures for 2007 to 2015 are taken from Department for Education, Special educational needs in England: January 2016. Figures for 2016 to 2023 are taken from Department for Education, Special educational needs in England, academic year 2023/24.

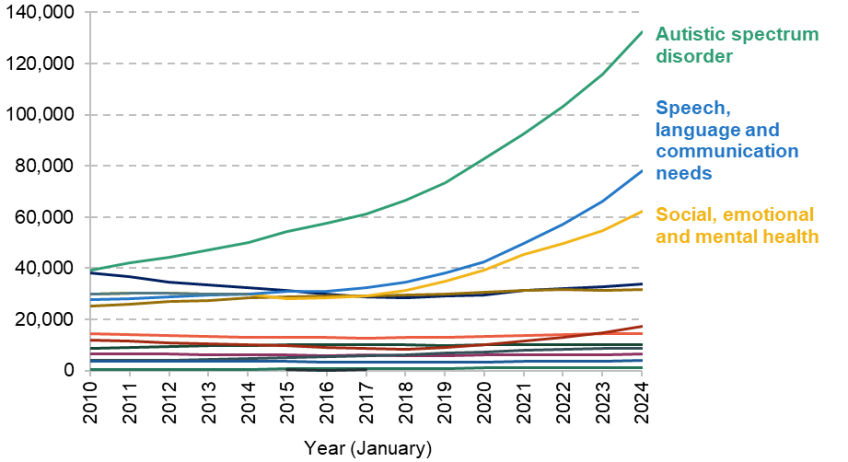

Breaking this rise in EHCPs down by type of need can somewhat inform why it has taken place. As Figure 2 shows, the recent rise in pupils with EHCPs has been driven by three main types of need: autistic spectrum disorder (ASD); speech, language and communication needs; and social, emotional and mental health needs. In particular, pupils with ASD now make up one-third (33%) of pupils with EHCPs, up from just 16% of pupils with statements of SEN in 2010.

Figure 2. Pupils with statements of SEN or EHCPs, by primary type of need

Note and source: Figures do not include pupils in independent schools. From 2016, the category ‘behavioural, emotional and social difficulties’ was phased out and a new category, ‘social, emotional and mental health’, was put in place; the two are combined here but are not exactly contiguous. Figures for 2010 to 2015 are taken from Department for Education, Special educational needs in England: January 2015. Figures for 2016 to 2023 are taken from Department for Education, Special educational needs in England, academic year 2023/24.

The rise in ASD among pupils with EHCPs has been occurring since at least 2010, with a particularly steep increase since roughly 2017. This trend mirrors rates of ASD among the total pupil population, with overall rates increasing from 0.7% in 2010 to 1.2% in 2016 and 2.6% in 2024. The precise determinant of this rise is unclear, but in part may be due to increased awareness of ASD, as well as differences in how it manifests among children and young people. For instance, while males still outnumber females among pupils diagnosed with autism by almost 3:1, the number of pupils with ASD has doubled for males between 2016 and 2024, but has almost quadrupled for females. This perhaps reflects better recognition of ASD symptoms among women and girls.

This trend in rising rates of ASD, particularly in recent years, can be seen across a range of countries (Zeidan et al., 2022). Data among 8-year-olds in the US, for instance, show a similar increase in ASD prevalence from 0.67% in 2000 to 2.76% in 2020 (Maenner et al., 2023), and a range of countries show similarly narrowing gaps between men and women (Li et al., 2022). Exactly when this rise began is unclear, however. ASD prevalence is generally higher in high-income countries, but there is some evidence to suggest that the rates among children in the UK are relatively high by international and European standards (Sacco et al., 2022). This relative comparability with some other similar countries helps to suggest that the increase in pupils with SEN and EHCPs is in part driven by broader trends of increased prevalence or recognition of ASD rather than just the nature of the English SEN system.

The category ‘social, emotional and mental health needs’ includes children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). There have been large rises in the number of children and young people diagnosed with ADHD in the UK (McKechnie et al., 2023) and in other countries (Abdelnour, Jansen and Gold, 2022).

There has also been a step change in mental health needs since the pandemic, particularly amongst young girls (Farquharson et al., 2024). This appears to be a global phenomenon too, with young people in other countries also experiencing declining mental health. A recent UNICEF study (2024) provides evidence of declining life satisfaction among 15-year-olds across Europe; in the US, Lin, Parker and Horowitz (2024) find worsening behaviour in schools; and an OECD study (2021) finds that mental health problems amongst young people doubled during the pandemic. There are also large barriers and delays in accessing child and adolescent mental health services in England (Children’s Commissioner, 2024).

The rise in speech, language and communication difficulties may be linked to difficulties accessing specific services, with long waits for accessing speech and language therapy at present (Roberts, 2024).

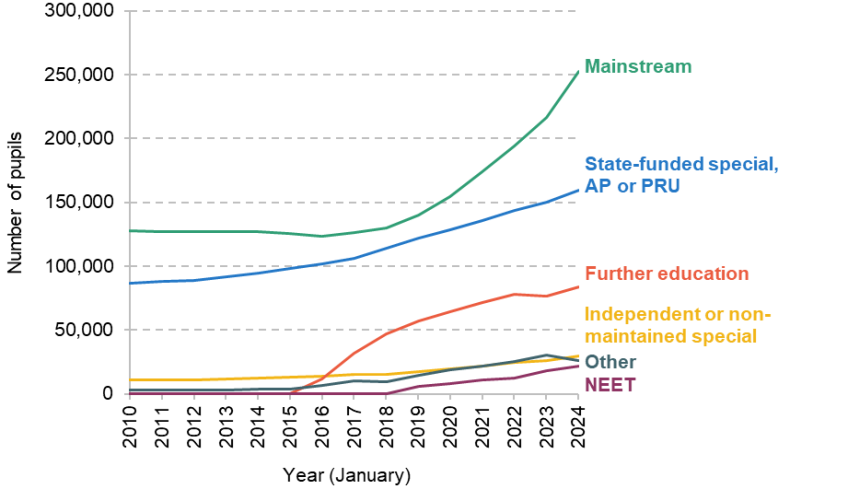

The vast majority (approximately 99%) of pupils with SEND, but without EHCPs, are educated in mainstream schools.3 By contrast, the composition of school type attended among children and young people with statements of SEN or EHCPs has fluctuated over time (Figure 3). As we set out in the next section, this has significant implications for spending. Since 2010, the number of pupils placed in special schools has steadily increased, while the number in mainstream schools remained static until 2018. This may be indicative of parental preference for special schools but may also be shaped by incentives for mainstream schools to reduce the amount spent on high-needs pupils. However, since 2017, the increase in special school places has not kept pace with the rapid rise in pupils with EHCPs. The number of pupils with EHCPs in mainstream schools has risen sharply from 126,000 in 2017 to 252,000 in 2024. This has likely placed strain on the ability of mainstream schools to cater for pupils with high needs, which could itself have increased parental preference for specialist settings. We also see a large percentage rise in the number of pupils in independent or non-maintained special schools, which has more than doubled from 13,000 in 2015 to nearly 30,000 in 2024. Whilst small in absolute number, the higher per-pupil cost of independent special schools (£61,500) relative to state-funded special schools (£23,900) means that this rise has significant financial implications (National Audit Office, 2024). The inclusion of further education (FE) colleges in the new EHCP system accounts for the significant rise in further education settings (colleges used to receive some high-needs funding through a separate system).

Figure 3. Number of children and young people with statements of SEN or EHCPs, by school type

Note and source: AP = alternative provision. PRU = pupil referral unit. NEET = not in education, employment or training. ‘Mainstream’ includes maintained, academy and independent non-special schools, as well as SEN units within these. Data from Department for Education, Education, health and care plans, reporting year 2024.

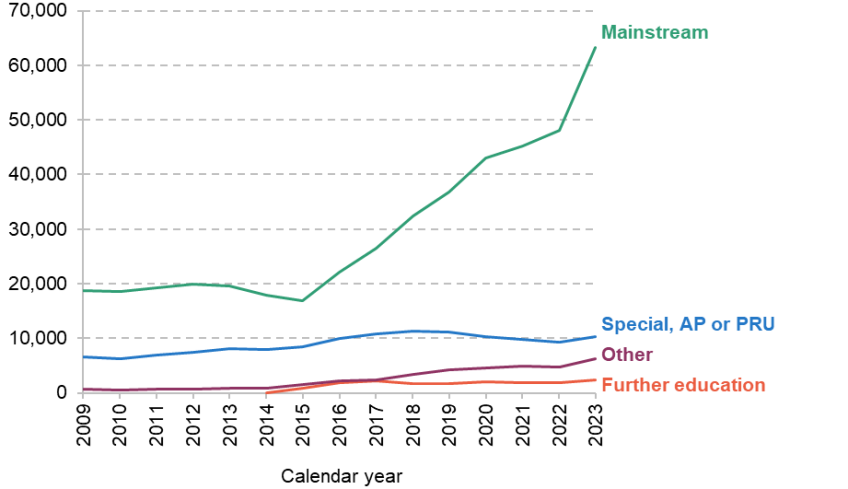

This trend of pupils with EHCPs increasingly going into mainstream schools looks set to accelerate. The share of pupils with new EHCPs who attend a mainstream school has risen from around 60% in 2015 to 75% in 2023, while the corresponding share for special schools has fallen from around 30% to 10% (Figure 4). Essentially, the absolute numbers of pupils with new EHCPs entering non-mainstream education each year have remained fairly stable over this period (although still higher than the rate at which pupils leave non-mainstream education), and most ‘additional’ pupils over 2015 numbers have entered mainstream schools. Furthermore, among pupils with new EHCPs, the total number entering state special schools each year has actually fallen since 2015, likely indicative of capacity constraints (Booth, 2024a). Such constraints may also help to account for the doubling of the numbers of pupils with EHCPs in independent special schools since 2015, a particular source of cost pressures.

Figure 4. Number of new EHCPs, by school type

Note and source: Figures do not include discontinued EHCPs and so will not correspond to increases in numbers by school type in Figure 3. ‘Mainstream’ includes maintained, academy and independent non-special schools, as well as SEN units within these. AP = alternative provision. PRU = pupil referral unit. Data from Department for Education, Education, health and care plans, reporting year 2024.

Local variation

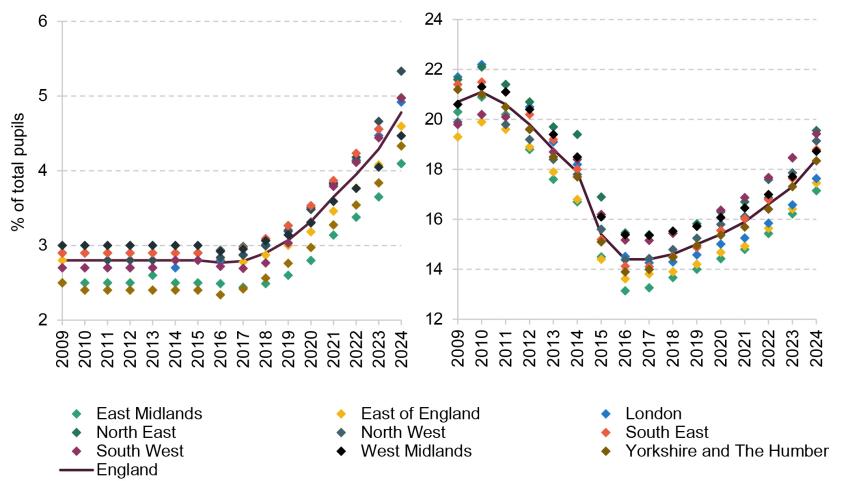

Across regions and local authorities, most see similar trends in total SEN and EHCP rates over time, with some increase in the variation of EHCP rates (Figure 5). However, there is substantial variation in the initial rate of identified SEND across areas, meaning that overall rates of pupils with SEND and EHCPs consistently differ between areas. In 2023–24, for instance, the share of pupils with an EHCP was 30% higher in the North West than in the East Midlands, and at the local authority level the share of pupils with an EHCP in Tower Hamlets was three times that of Nottinghamshire (6.8% and 2.3% respectively).4 This might reflect objective differences in need across areas, but may also be due to differences in available funding as well as practices around identification and assessment of needs. It is unclear which is the case, but better understanding these drivers could be an important element of better allocating funding in accordance with need.

Figure 5. Share of pupils with EHCPs and all SEND (including EHCPs), nationally and with regional spread

(a) Statements of SEN or EHCPs (b) Total SEND

Source: Figures for 2007 to 2015 are taken from Department for Education, Special educational needs in England: January 2015. Figures for 2016 to 2024 are taken from Department for Education, Special educational needs in England, academic year 2023/24.

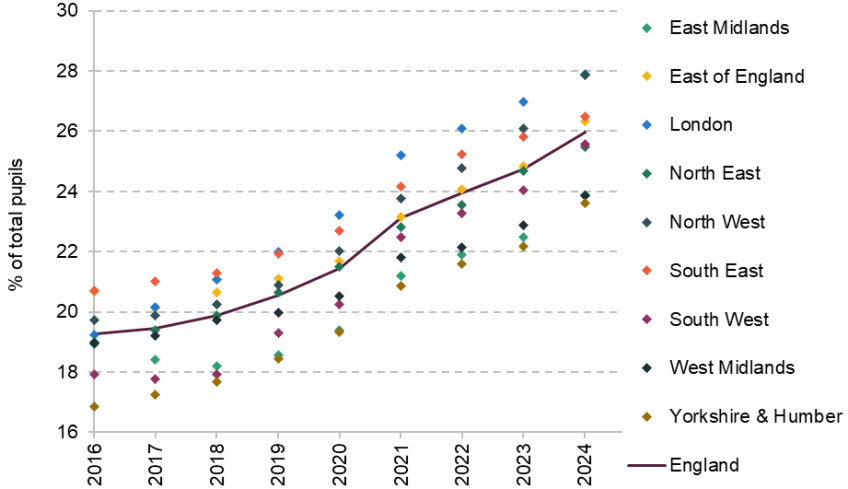

Regional disparity also exists in terms of the share of all pupils with SEND who have EHCPs (Figure 6). Again, regions have seen similar increases in the share of pupils with SEND who have EHCPs but initial differences between them remain fairly stable across time. There could be a variety of reasons to explain this. First, different areas might see different prevalences of need types, some of which require more specialist support than others. Second, different areas might offer different amounts of high-needs support which might attract pupils into their schools. Third, different councils may be more or less stringent in granting assessments and requests for EHCPs. Fourth, different areas may have different practices and incentives around identifying SEN and seeking specialist support.

Figure 6. Share of total pupils with SEND who have EHCPs, nationally and with regional spread

Source: Department for Education, Special educational needs in England, academic year 2023/24.

With respect to the first mechanism, accounting for differences in types of need does not remove the regional disparities in EHCP issuance. Indeed, if we just focus on ASD (the most prevalent type of need), the regional gaps in EHCP issuance actually increase: pupils with ASD in London are 16 percentage points more likely to have EHCPs than those in the West Midlands,5 a gap which has remained stable since 2016. Differences between individual local authorities are even greater: in 2024, Tower Hamlets saw 84% of pupils with ASD on EHCPs compared with just 32% in Coventry. Discrepancies of a similar proportion exist across a range of need types. The second mechanism – of pupil transfer across areas – also seems not to fully account for these differences in EHCP prevalence: although some councils with the highest shares of EHCPs among SEND students do take in more high-needs pupils than they ‘export’, so do most councils with a lower burden of need, perhaps as they have greater capacity for additional high-needs pupils.6

Local differences in granting EHC assessments and plans also do not seem to account for the gap. Although there are regional disparities in refusing EHCP assessments (from 18.1% in the North West to 27.8% in the North East, for 2023) and in not issuing EHCPs following an assessment (from 2.5% in the East of England to 7.6% in the North East), these do not correspond to the regions that see unusually high or low rates.7 Instead, this suggests that, for some reason, different areas see significantly different rates of requests for EHCP assessments for high-needs pupils, although the precise reason behind this is unclear. Indeed, an earlier study suggests that these discrepancies may arise at the school level (Hutchinson, 2021), although other explanations could include different parental attitudes or differences in intensity of need that we do not observe in the data.

As we discuss in the next section, it is the rise in EHCP numbers that has put particular strain on high-needs spending, given they come with statutory obligations. Understanding why the number of pupils with EHCPs has risen so dramatically in recent years is therefore crucial to understanding how to respond to this high-needs funding crisis. As discussed earlier, better understanding and recognition of needs such as autism have likely played a role in increasing rates of SEND and EHCPs, and this is likely to remain a pressure over coming years as more people join waiting lists for assessment.8

Beyond this, the consistent regional and local variations in rates of need suggest differences in practices and incentives to identify SEND and request EHCPs across the country. Plausibly, these more systemic factors behind SEND identification and EHCP issuance may be partly responsible for the recent trajectory of EHCP rates at a national level. Often this is linked to the reforms introduced in 2014 (National Audit Office, 2024; Isos Partnership, 2024) but, as we have set out, it is unclear that EHCPs were a significantly more attractive option than the previous statements of SEN, or that the increase in demand for specialist provision began in 2014. Instead, in the next section, we will discuss how drivers of high-needs demand might link to funding systems and levels.

3. The pressure on budgets

The context for reforms to SEND funding is challenging, to put it mildly. The rapid rises in the number of pupils with EHCPs have put huge pressure on high-needs budgets. Funding has risen significantly, but spending has tended to be higher and rise at a faster rate. This has led to large local authority deficits. Local authorities are not allowed to run deficits and must issue a section 114 notice if spending is expected to exceed income, i.e. declare bankruptcy. In an effort to avoid this scenario in 2020, the then government introduced something called the ‘statutory override’, which separates deficits on the Dedicated Schools Grant (DSG) from the rest of local authority accounts. To be blunt, the government effectively moved high-needs deficits off the balance sheets of local authorities. The statutory override was meant to expire in March 2023, but has been extended to March 2026. The previous government also entered into ‘Safety Valve’ agreements with 33 local authorities with the highest deficits. In return for extra grants to clear accumulated deficits, local authorities agreed to cut spending to ensure a balanced high-needs budget in future. The majority of local authorities in this programme expect to achieve a balanced budget at some point between 2026 and 2032, well after the end of the statutory override (National Audit Office, 2024).

Total funding and spending

The vast majority of funding for high needs comes from the high-needs block of the DSG. Since 2018, these blocks have been ring-fenced, with transfers between them mostly limited to 0.5% of the schools block. Other sources of funding include the additional Safety Valve funding, direct funding of places in academies and free schools by the Education and Skills Funding Agency (ESFA), and teacher pay grants for teachers in special schools. As these are set centrally and the ability to transfer money from other elements of schools spending has become extremely limited since 2018, there is very little flexibility or council discretion over the level of high-needs funding.

As shown in Figure 7, actual spending on high needs (that draw from DSG funds) rose by about £3.2 billion or 45% in real terms between 2015–16 and 2022–23. Spending plans by local authorities imply further growth of 13% or £1.4 billion between 2022–23 and 2024–25. If realised, this would equate to total growth of £4.5 billion or 64% between 2015–16 and 2024–25. In reality, actual spending has tended to significantly exceed planned spending in recent years, which means the true growth in spending may be even higher.

Figure 7. High-needs spending and estimated funding, 2024 prices

Note and source: High-needs funding is based on Dedicated Schools Grant high-needs block, pre-deductions for direct funding of high-needs places by ESFA, Teacher Pay Grants, Teacher Pension Employer Contribution Grants paid to special schools when not included in schools NFF, and Safety Valve funding. Indicative schools block transfers of 0.5% are shown as dotted. Spending covers allowable expenditure from the high-needs block, which includes sections 1.0.2, 1.2 and 1.4.11 of section 251 out-turns. Spending on place funding was not collected from 2015–16 to 2017–18 so is estimated from planned spending data. Direct place funding by ESFA is imputed using values in DSG allocations. Planned spending is used from 2023–24 and includes teacher pension grants for 2024–25. Prices are adjusted using the June 2024 GDP deflator figures; see GDP deflators at market prices, and money GDP. DSG figures are from Education and Skills Funding Agency, Dedicated Schools Grant (DSG): 2024 to 2025 and previous series. Expenditure is from Department for Education, LA and school expenditure, financial year 2022-23 andPlanned LA and school expenditure, financial year 2024-25.

As can be seen, the growth in funding has been slower than the growth in spending, particularly between 2017 and 2021. This gap then narrowed, with the growth in total funding and spending being relatively similar up to 2022–23. In reality, local authorities can (and often do) transfer up to 0.5% of their core mainstream schools’ budget to partially plug this deficit, as shown by the dashed line. However, even including such transfers, government figures quoted by the National Audit Office (2024) suggest that local authorities had accumulated deficits of at least £1.5 billion in aggregate by 2022–23.

Since 2022–23, the gap between planned spending and funding has grown further, with a gap of £700 million by 2024–25. The true gap is likely to be even larger given that actual spending has tended to overshoot spending plans. Reflecting such trends, government figures quoted by the National Audit Office (2024) suggest accumulated deficits of at least £3.3 billion in 2024–25. The statutory override keeps these deficits effectively off the books, preventing many local authorities from having to declare bankruptcy.

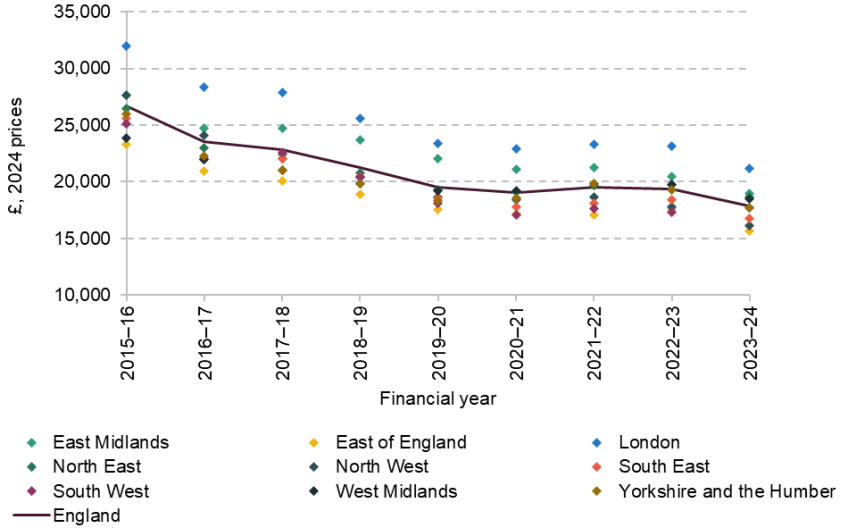

Rapid rises in the numbers of pupils with SEND (outlined in Section 2) have led to a significant fall in both funding and spending per EHCP (Figure 8). Since 2015–16, per-EHCP funding has fallen by almost a third, amounting to a nearly £9,000 real-terms fall by 2023–24. Some of this drop can be accounted for by the expansion of EHCPs to over-18s, who generally attract much less high-needs spending (see post-16 top-up funding in Figure 9 later). However, even when limiting this analysis to those with EHCPs in schools, per-EHCP funding has still fallen by over £5,000 since 2015–16.

Figure 8. High-needs spending and estimated funding, per EHCP, 2024 prices

Note and source: See Figure 7 for notes on spending and funding numbers and price adjustments. EHCP numbers are for the January of each financial year and cover all children and young people with EHCPs; source: Department for Education, Education, health and care plans, reporting year 2024.

In terms of spending, the demand-led nature of the SEND system means that councils are obligated to provide the support set out in EHCPs. This means that, in practice, councils have a limited say in the minimum they must spend on high needs. Furthermore, given that this specialist provision can be quite expensive, this takes up the bulk of the high-needs block allocated to each council and so there is not much ‘excess’ (non-obligatory spending) that can be cut back on. As a result, high-needs expenditure per EHCP fell slightly less dramatically than funding from 2015 to 2020, resulting in increased in-year funding and spending gaps and so substantial deficits in many councils’ high-needs budgets.

Categories of spending

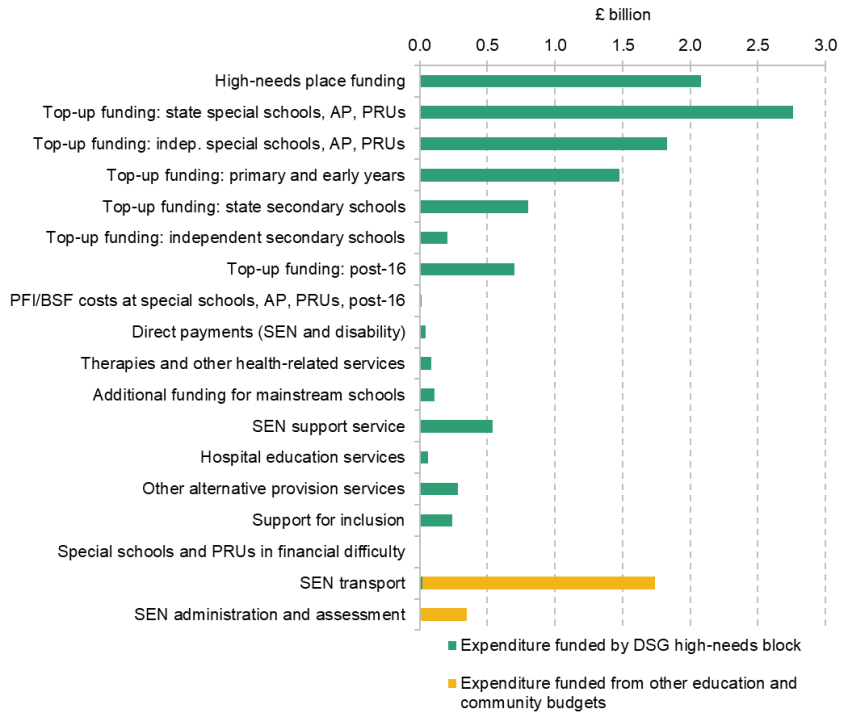

Spending on high needs can cover a broad range of areas, but expenditure funded from the DSG is concentrated on providing funding for pupils in state-funded special schools (£2.1 billion in place funding and £2.8 billion in further top-up funding planned for 2024–25), funding fees for pupils in independent special schools (£1.8 billion for 2024–25) and top-up funding to mainstream schools (£2.3 billion for 2024–25).

As can be seen in Figure 9, there may be room for making savings in some areas of high-needs spending, such as assessments, administration and transport. Indeed, spending on areas such as SEN administration and transport increased significantly between 2015–16 and 2022–23 (by around £176 million and £719 million in real terms respectively). However, the vast majority of these costs are funded by sources of council funding beyond the DSG high-needs block9 and so only constitute additional pressures on local authorities beyond the deficits in high-needs schools budgets that we set out.

Figure 9. Breakdown of planned spending on high needs by category, 2024–25

Note and source: AP = alternative provision. PRU = pupil referral unit. PFI = Private Finance Initiative. BSF = Building Schools for the Future. See Figure 7 for notes on spending and funding numbers. Expenditure from the other education and community budget is composed of lines 2.1.2, 2.1.4, 2.1.6 and 2.1.7 of section 251 returns. Non-maintained providers included in ‘independent’.

Figure 10 shows increases since 2015–16 in spending by category, based on actual spending up to 2022–23 and then incorporating planned changes up to 2024–25. Increases in high-needs spending have almost exclusively gone towards greater top-up funding for schools, which covers the extra funding required over and above the first £6,000 of additional SEND provision costs in mainstream schools and over the £10,000 core per-place funding in specialist settings. This increase in top-up funding has been mostly focused on state-funded and independent special schools: £1.8 billion of the £2.8 billion real-terms increase in spending between 2015–16 and 2022–23 (excluding place funding) has gone to top-up funding for state-funded and independent special schools. This increase in special school top-up funding has been fairly evenly split between the state-funded and independent sectors, with a £900 million rise in top-up funding in each sector. However, independent and non-maintained special schools contain a much smaller number of pupils (31,500) than state-funded special schools, AP and PRUs do (172,800). The reason for the high increase in the cost of independent and non-maintained top-ups is because of the much higher per-pupil cost of provision (£61,500) than in state-funded special schools (£23,900) (National Audit Office, 2024).

Figure 10. Change in expenditure from 2015–16 to 2022–23 (actual) and 2024–25 (planned), by category of high-needs expenditure, 2024 prices

*High-needs place funding is the change from 2018–19 as this was the first time spending data were collected separately for this category.

Note and source: Non-maintained providers included in ‘independent’. Only includes expenditure that can be funded from the DSG high-needs block. Expenditure is from Department for Education, LA and school expenditure, financial year 2022-23 and includes section 1c high-needs spending, 1.4.11 and 1.0.2. Direct place funding by ESFA is imputed using values in DSG allocations; see Education and Skills Funding Agency, Dedicated Schools Grant (DSG): 2024 to 2025 and previous series. Prices are adjusted using the June 2024 GDP deflator figures; see GDP deflators at market prices, and money GDP.

Differences across areas

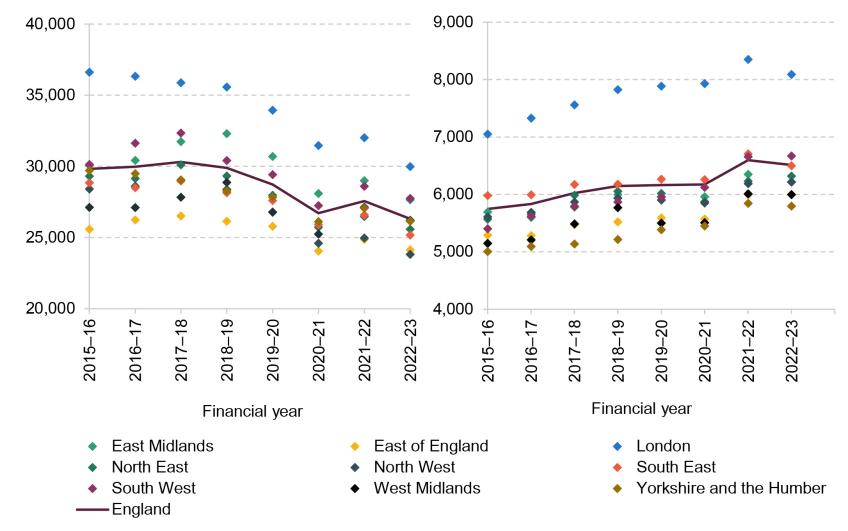

The impact of high-needs budget pressures has not been evenly felt across areas due to different rates of SEND and EHCPs among pupils. A further component of regional inequalities comes from the different funding levels for high needs that councils are allocated. These allocations are determined by the National Funding Formula (NFF). This formula incorporates a basic per-pupil amount, proxies for need (such as deprivation and child health levels) and a component based on historical spending in 2017–18. The historical spend element determines 25% of the overall formula allocation and drives a large element of the variation in funding across areas. This bakes in some fairly arbitrary differences in council funding that have arisen over time, and lead to large variability in funding per high-needs pupil across councils (Figure 11). Naturally, this also translates to differences in per-pupil spending across councils (Figure 12).10

Figure 11. High-needs funding per EHCP, nationally and with regional spread

Note and source: See Figure 7 for notes on how funding is measured and prices adjusted; these figures exclude any schools block transfers made. EHCP numbers are from Department for Education, Education, health and care plans, reporting year 2024.

Figure 12. High-needs expenditure per EHCP and per high-needs pupil, nationally and with regional spread (£, 2024 prices)

(a) Per EHCP (b) Per high-needs pupil

Note and source: Expenditure is from Department for Education, LA and school expenditure, financial year 2022-23 and includes section 1c high-needs spending, 1.4.11 and 1.0.2. Direct place funding by ESFA is imputed using values in DSG allocations; see Education and Skills Funding Agency, Dedicated Schools Grant (DSG): 2024 to 2025 and previous series. ‘High-needs’ pupils include those with identified SEND as well as those with EHCPs. Prices are adjusted using the June 2024 GDP deflator figures; see GDP deflators at market prices, and money GDP.

These local differences in need and funding contribute to variability in deficits across councils. As implied by Figure 7, national in-year gaps between spending and estimated funding for high needs (excepting any transfers from the schools block) averaged around £480 million between 2018–19 and 2022–23. Even allowing for local authorities transferring 0.5% of their schools block into the high-needs block, in-year gaps between funding and spending still average £260 million over this period. This is very consistent with government figures showing accumulated deficits of £1.5 billion by 2022–23.

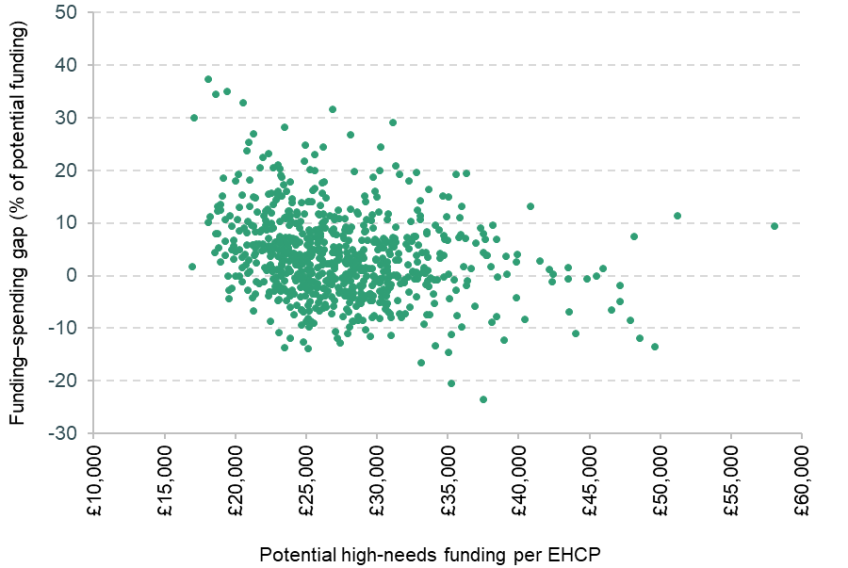

Some local authorities have much greater gaps between funding and spending than others. Furthermore, it is the ones that receive lower levels of per-EHCP funding that seem more likely to overspend relative to their high-needs funding (Figure 13). In some sense, this is obvious given the limited flexibility councils have over how much they spend on high needs and the very broad-based rise in EHCPs. However, it provides a strong case that any reform to the high-needs funding system must take steps towards rectifying these geographical discrepancies in funding in order to bring down deficits most effectively.

Figure 13. Percentage funding–spending gap against potential funding per EHCP, by local authority, 2018–19 to 2022–23 (gap is positive if spending is greater than funding)

Note and source: City of London and Isles of Scilly are excluded, as are Newham and Shropshire as outliers. See Figure 7 for notes and sources for estimation of funding, spending, potential funding and price adjustment.

These pressures on councils’ high-needs budgets also feed into pressures on schools, which data for 2022 show make up the bulk of requests for EHCP assessments (Booth, 2024b). As previously mentioned, mainstream schools have to fund up to the first £6,000 in additional provision costs for pupils with SEND before they can access top-up funding from their council’s high-needs budget. This threshold has remained the same since its introduction in 2014, and therefore its erosion in real terms may have had a mechanical effect of bringing more high-needs pupils into the group who require top-up funding, for which an EHCP is often tacitly a requirement. Regarding the costs that mainstream schools are expected to pay themselves, as school funding has fallen in per-pupil terms since 2010 (Sibieta, 2024) and the notional amounts allocated to SEN budgets have been fairly stagnant in real terms since at least 2020,11 it is likely that the ability of mainstream schools to support high-needs pupils from their core budgets has been strained. As the only route to additional funding is through pupil-led top-up funding, this may further incentivise parents and schools to seek EHCPs.

These pressures on mainstream schools may also have contributed to the substantial increase in costs that special school placements have generated. Given the increasing budget pressures, there is some evidence that mainstream schools have been incentivised to ‘off-roll’ pupils who generate high costs – for instance, by trying to have them placed in special schools instead, for which again an EHCP is almost always required (Ofsted, 2019). Attainment targets can also contribute to these incentives to off-roll high-needs pupils, although as illustrated earlier, capacity constraints in special schools have limited the rise in numbers in recent years (National Audit Office, 2024).

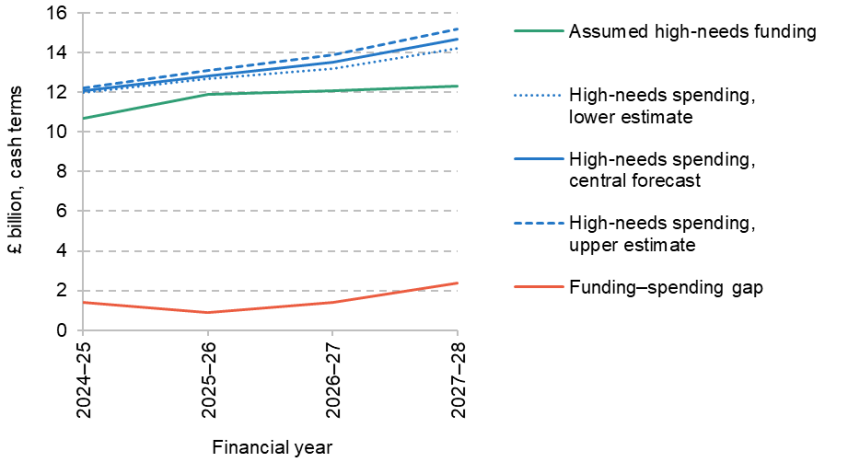

Looking to the future, government forecasts imply things are likely to get much worse without extra funding or significant reform to the system. The National Audit Office (2024) estimates that the gap between funding and spending was about £1.4 billion in 2024–25, and quotes government forecasts for annual spending needs increasing by at least £2–3 billion in cash terms between 2024–25 and 2027–28. These forecasts were published before the government added £1 billion to the high-needs budget for 2025–26, which will likely reduce the gap between funding and spending to around £900 million in 2025–26. However, because of continued forecast growth in numbers, the gap between spending and funding would still likely rise to about £2.4 billion in 2027–28 under current forecasts for spending and assuming a real-terms freeze in funding (Figure 14).

Figure 14. Forecasts for high-needs funding and spending, cash terms

Note and source: Figures from National Audit Office (2024) and Autumn Budget 2024.

If realised, the implied spending gaps over the next three years would add about £4.7 billion to local authority accumulated deficits. These are already estimated to be at least £3.3 billion in 2024–25. Adding these together would give a total accumulated deficit of over £8 billion by 2027–28.

4. Policy options

It is widely accepted that the SEND system is in need of major reform, both to control costs and to improve provision. In this final section, we set out the potential advantages and drawbacks of a broad set of policy options. There is no shortage of policy options and it is likely that the government will want to make multiple changes. All of the options are challenging and costly. The ‘right’ option will depend on how much of the rise in EHCPs is due to an objective rise in very high needs among young people or increased recognition of needs, as opposed to financial and legal incentives for less severe needs to be met by the costly statutory system of EHCPs. Both effects are likely to be at play.

If one thinks that most of the rise has been driven by increased needs or better identification of needs that were always there, then the best approach is likely to involve expanding current provision to meet that need and finding the best ways to assess how to meet those needs (i.e. specialist versus mainstream provision). Here, we note that the rises in ASD, ADHD and mental health needs appear to be global phenomena across high-income countries.

Alternatively, one might think that numbers and costs have been driven by financial incentives to seek EHCPs for less severe needs, the statutory obligations attached to EHCPs, poor practice, and seemingly artificial separations between high-needs and mainstream education budgets. In this case, the best response is likely to be cost-saving measures and legal/funding reforms. Indeed, the present system of ring-fenced funding blocks, a cash-terms freeze in the top-up funding threshold, and top-up funding being generally limited to specific pupils with EHCPs are likely to have played an important role in escalating EHCPs.

For its part, the government has already set out a clear preference for increasing core provision in mainstream schools and has announced £740 million in capital funding to help schools make adjustments.12 However, sufficiently expanding core provision to accommodate rising need is likely to require much more than this. This is likely to be challenging and it is important to consider the full range of options.

The first (default) option is to continue with the current system of pupil-led top-up funding for EHCPs. This is not an easy option. On current forecasts, the number of pupils with EHCPs is expected to rise significantly and annual spending is forecast to increase by at least £2–3 billion between now and 2027. Much of this extra spending flows directly from statutory obligations and, without extra funding, would likely increase local authorities’ high-needs deficit to over £8 billion. If accounted for in the normal way, this would lead to widespread local authority bankruptcies. Continuing with the current system would lead to over 5% of pupils (and rising) going through the costly and combative EHCP assessment system.

The second option is to seek to deliver provision in a more cost-effective way, without affecting overall quality. This is, in essence, the approach of the so-called Safety Valve programme, which provides extra grants to local authorities with the largest high-needs deficits on the condition that they reduce costs. This programme has seen some financial success, with 22 of the 33 local authorities with the highest deficits on course to deliver expected savings. The high and ever-expanding cost of independent school placements further suggests opportunities for cost savings. However, the vast majority of the deficits will not be closed until between 2026 and 2032. Furthermore, this programme has been highly controversial, with concerns about cuts to provision and ongoing legal cases (Booth, 2024c). Whilst cost-saving measures are likely to be part of the solution, it is hard to believe they are the major element of the solution given the vast rises in numbers and spending. The government has already decided not to enter into any more Safety Valve agreements.

The third (connected) option would be to reform the system such that EHCPs no longer created statutory obligations. Instead, schools and local authorities would need to make best endeavours to deliver such provision and ration scarce resources. This is the normal way in which public spending and resources are allocated. Furthermore, the present system already includes rationing; it just happens through accessing assessments and legal tribunals. Enabling local authorities and providers to make plans to meet rising needs across the population as a whole may also be a more efficient and equitable way to deliver provision. This would clearly be attractive from a purely financial point of view, but it could be incredibly challenging from a political perspective given parents’ lack of trust in the current system to meet their children’s needs. However, it is still important and useful to consider this question. If we had a clear understanding as to exactly why EHCPs need to be attached to statutory obligations in the current system, we might have a better idea of how to reform the system (including wider aspects such as teacher training and accountability measures). What would need to change for parents to trust the system to meet their children’s needs without statutory obligations?

The fourth option is to provide further specific services to support children, including earlier interventions before problems become more severe and costly. This could include mental health services, speech and language therapy, and educational psychology. The current government has already committed to providing mental health support in all secondary schools, which may well ease some of the severe problems young people currently face in accessing mental health services. Improving access to educational psychology and speech and language therapy may well also be part of a sensible package of reforms. However, it is uncertain exactly how much of the increase in numbers could be avoided, or reduced in cost, by earlier intervention services. For example, could early intervention really ‘prevent’ the cost of providing for ASD needs?

The fifth option is to increase capacity in the state-funded specialist sector. This is almost certainly needed given that many special schools are at or over capacity, which has compelled many local authorities to fund more expensive provision in the independent sector. The previous government had already increased capital spending to increase the number of special school places. However, this is a costly and relatively slow process. Given the rapid increases in numbers of pupils with SEND, it also needs to be a conscious policy choice to increase the share of pupils taught within the specialist sector as this is a big change in the organisation of education. Historically, the specialist sector has accounted for about 1.4% of pupils. Key questions that should be considered include ‘What is the threshold of needs that requires specialist provision?’ and ‘How do we make judgements consistent and fair across local authorities?’.

The last option is to deliver more support within mainstream schools, which is clearly already a long-run priority for the new government. In many ways, this seems like the most natural option, but this is not simple either. It would be a massive change in what schools do and how they are funded. Schools would need to be able to offer core provision for pupils with a range of different types of SEND, and do so without affecting existing provision. Many pupils with SEND can present with challenging behaviour, which can be disruptive and take up staff time. Schools would need extra staff with the required skills, teachers would need to have further good-quality training, and extra physical space would be needed. Delivering a core offer is likely to be harder for smaller schools, given that types of needs and costs are likely to be more volatile for them. The funding system would need to totally change. The present high-needs funding system was introduced in 2018, when numbers were mostly stable, and it incorporates many historical measures of need and spending that already drive substantial geographical differences in spending per pupil. It is ill-designed for the present context of rising need and could not be used at a school level. It would be necessary to design a system based on more objective measures of need across schools and local authorities, and that allowed for greater flexibility in how funding could be allocated. This might include transferring more money to schools as core funding rather than top-up funding, and making access to top-up funding less reliant on having an EHCP (Mime, 2024). The accountability system may also need to change to account for more pupils with SEND in mainstream schools. These substantial changes would likely require extra investment spending, extra day-to-day spending and a lot of work in schools and government to prepare for change. The government has already provided some investment spending (about £740 million in 2025–26) but has not yet committed any day-to-day or resource spending.

In considering these potentially disruptive and costly policy options, it is tempting to step back from reform and change. However, it is important to restate that the default is for continued rises in numbers of pupils with EHCPs, extra spending of £2–3 billion per year and local authority deficits of £8 billion in three years’ time, pushing many to the point of bankruptcy.

Given the challenging and costly nature of the policy options, there is large interest in the appropriate transition path to a new system. This is not simple either. One can easily imagine a preferred policy package that involved more state-funded special school places for those with the highest needs and more early intervention services in mainstream schools to make up an expanded core offer for those with less severe needs. In the long run, one could credibly claim that such a system would reduce future spending needs and improve equity. In the short run, however, the transition is likely to pose major challenges. Delivering an expanded core offer is a big change to schools and requires up-front investment in people and buildings, but it is a necessary first step to build parental confidence. Savings will only then accrue as the mix of provision changes in the future or early intervention services bear fruit. In the short run, to deliver current obligations while expanding alternative forms of provision, a degree of double funding is almost certainly a necessary feature of an effective transition. This is an expensive and challenging thing to do at a national level.

In the end, one must confront powerful arguments and constraints working in opposite directions. On the one hand, the system is clearly in need of urgent, radical change and will push annual spending up by at least £2–3 billion in three years’ time without reform. On the other hand, the public finances are incredibly tight and the likely set of reforms represent controversial, massive changes to the school system. With this in mind, the most important thing the government can do is set out a clear long-term vision. The state of the public finances and an accumulation of evidence on the best approaches to delivery will then determine the pace of transition. It may be that local or regional trials end up being the only way to begin such a costly and challenging set of reforms. Schools within broad local areas could be asked to adapt existing high-needs provision into a broader and coordinated core offer in return for a set-up grant to ensure the core offer is greater than the sum of its parts. This would enable initial learning on how services could be combined and coordinated, and the extent to which savings are realised in the short run. There are lessons from the (ongoing) implementation of the National Funding Formula for schools. Such a reform was proposed many times from the early 2000s onwards, but was often rejected because of the degree of winners and losers from such a big change. In the end, it was introduced in 2018, but slowly and with lots of transitional protection. Indeed, transition is ongoing. However, there was a clear long-term vision of the school funding system that is well understood by schools and policymakers, and this acts as a force for continual change. The transition path to a better system may run slowly and through an accumulation of local knowledge, but it is probably better than no transition and continuing on the present path of financial unsustainability.

References

Abdelnour, E., Jansen, M. O. and Gold, J. A., 2022. ADHD diagnostic trends: increased recognition or overdiagnosis? Missouri Medicine, 119(5), 467–73. PMID: 36337990; PMCID: PMC9616454.

Booth, S., 2024a. Two-thirds of special schools full or over capacity, new data shows. Schools Week. https://schoolsweek.co.uk/two-thirds-of-special-schools-full-or-over-capacity-new-data-shows/.

Booth, S., 2024b. Pushy parents ‘not to blame’ as schools lead surge in bids for EHCPs. Schools Week. https://schoolsweek.co.uk/pushy-parents-not-to-blame-as-schools-lead-surge-in-bids-for-ehcps/.

Booth, S., 2024c. SEND: DfE finally considers pupil impact of safety valve scheme. Schools Week. https://schoolsweek.co.uk/send-dfe-finally-considers-pupil-impact-of-safety-valve-scheme/.

Children’s Commissioner, 2024. Children’s mental health services 2022-23. https://www.childrenscommissioner.gov.uk/resource/childrens-mental-health-services-2022-23/.

Department for Education, 2011. Support and aspiration: a new approach to special educational needs and disability – consultation. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/support-and-aspiration-a-new-approach-to-special-educational-needs-and-disability-consultation.

Department for Education, 2012. School funding reform: arrangements for 2013 to 2014. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/school-funding-reform-arrangements-for-2013-to-2014.

Department for Education, 2013. School funding reform: findings from the review of 2013 to 2014 – arrangements and changes for 2014 to 2015. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/school-funding-reform-findings-from-the-review-of-2013-to-2014-arrangements-and-changes-for-2014-to-2015.

Department for Education, 2023. SEND and alternative provision improvement plan. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/send-and-alternative-provision-improvement-plan.

Department for Education and Department of Health, 2014. Special educational needs and disability code of practice: 0 to 25 years. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/send-code-of-practice-0-to-25.

Farquharson, C., McKendrick, A., Ridpath, N. and Tahir, I., 2024. The state of education: what awaits the next government? Institute for Fiscal Studies, Report 317, https://ifs.org.uk/publications/state-education-what-awaits-next-government.

Hutchinson, J., 2021. Identifying pupils with special educational needs and disabilities. Education Policy Institute, Report, https://epi.org.uk/publications-and-research/identifying-send/.

Isos Partnership, 2024. Towards an effective and financially sustainable approach to SEND in England. Isos Partnership Report commissioned by the Local Government Association and County Councils Network, https://www.local.gov.uk/publications/towards-effective-and-financially-sustainable-approach-send-england.

Li, Z., Yang, L., Chen, H., et al., 2022. Global, regional and national burden of autism spectrum disorder from 1990 to 2019: results from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences, 31, e33, https://doi.org/10.1017/S2045796022000178.

Lin, L., Parker, K. and Horowitz, J., 2024. What’s it like to be a teacher in America today? Pew Research Centre, https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2024/04/04/whats-it-like-to-be-a-teacher-in-america-today/.

Maenner, M. J., Warren, Z., Williams, A. R., et al., 2023. Prevalence and characteristics of autism spectrum disorder among children aged 8 years — Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 11 sites, United States, 2020. MMWR Surveillance Summaries, 72(2), 1–14, http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.ss7202a1.

McKechnie, D. G. J., O’Nions, E., Dunsmuir, S. and Petersen, I., 2023. Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder diagnoses and prescriptions in UK primary care, 2000–2018: population-based cohort study. BJPsych Open, 9(4), e121, https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2023.512.

Mime, 2024. Inclusion in London’s schools: a review of inclusion of young people with SEND in London. Commissioned by London Councils, https://www.mimeconsulting.co.uk/report-launch-send-inclusion-london-schools/.

National Audit Office, 2024. Support for children and young people with special educational needs. NAO Report, https://www.nao.org.uk/reports/support-for-children-and-young-people-with-special-educational-needs/#downloads.

OECD, 2021. Supporting young people’s mental health through the COVID-19 crisis. OECD Policy Responses to Coronavirus (COVID-19), https://doi.org/10.1787/84e143e5-en.

Ofsted, 2019. Off-rolling: exploring the issue. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/off-rolling-exploring-the-issue.

Roberts, J., 2024. Record speech and language waits ‘damaging’ pupils’ chances. TES Magazine, https://www.tes.com/magazine/news/general/record-speech-and-language-waits-damage-pupils-chances-heads-warn.

Sacco, R., Camilleri, N., Eberhardt, J., et al., 2022. The prevalence of autism spectrum disorder in Europe. In M. Carotenuto (ed.), Autism Spectrum Disorders – Recent Advances and New Perspectives. http://dx.doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.108123.

Sibieta, L., 2024. School spending in England: a guide to the debate during the 2024 general election. Institute for Fiscal Studies, Report 316, https://ifs.org.uk/publications/school-spending-england-guide-debate-during-2024-general-election.

UNICEF, 2024. Child and adolescent mental health. Policy Brief, https://www.unicef.org/eu/media/2576/file/Child%20and%20adolescent%20mental%20health%20policy%20brief.pdf.

Zeidan, J., Fombonne, E., Scorah, J., et al., 2022. Global prevalence of autism: a systematic review update. Autism Research, 15(5), 778–90, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9310578/.