Rishi Sunak has pledged that, should he become Prime Minister, the basic rate of income tax would fall to 16% by the end of the decade. That would be a 3 percentage point (ppt) cut on top of the 1ppt cut (from 20% to 19%) already planned for 2024-25. That 1ppt cut will cost about £6bn per year; the additional cut to 16% now proposed by Mr Sunak would cost an additional £19bn per year.

This is a very substantial tax cut. But it is still considerably smaller than the net tax rise announced by Mr Sunak as Chancellor, which was comfortably more than twice as large. The additional 3ppt income tax cut costs about as much as the multi-year freeze to income tax thresholds was forecast to raise back in March - a policy which will have since grown in size due to rising inflation. We have also had the recently-implemented rise in the NICs rate (which Liz Truss plans to reverse) and the planned corporation tax rise (which Ms Truss plans to cancel). Mr Sunak’s new policy would still leave the total tax take, as a proportion of national income, at its highest level since around the early 1950s.

Based on the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR)’s March forecasts, the additional £19bn of borrowing required to fund Mr Sunak’s proposed income tax cut could be met without breaching the government’s self-imposed fiscal rules (because the government was forecast to meet those targets with £30bn or so of ‘headroom’ to spare). But those forecasts were subject to substantial uncertainty, and the global economic outlook has deteriorated since the spring. It is not difficult to imagine a world where that headroom disappears, and where a £19bn tax cut puts adherence to those fiscal targets at risk. Ms Truss’ proposed package of tax cuts is considerably larger than Mr Sunak’s and, accordingly, would be more likely to breach the current set of fiscal targets.

Where does this leave the big picture comparison between Mr Sunak’s and Ms Truss’ tax proposals? In the short term, nothing has changed: Mr Sunak proposes a temporary abolition of VAT on fuel as his only immediate change to current policy plans, while Ms Truss plans more than £30bn of tax cuts, relative to current plans, very quickly. To the extent that imminent tax cuts would add to the current considerable inflationary pressures - which they would, although it is hard to say by how much - and prompt the Bank of England to increase interest rates, this remains something that is much more likely under Ms Truss’ plans than under Mr Sunak’s.

In the longer term, the biggest difference between the two candidates’ tax plans is one of scale and timing, not direction of travel. Both candidates are now proposing substantial tax cuts relative to current government plans without reference to any of the spending cuts which would, in the end, have to accompany them. Mr Sunak’s indication that an income tax cut would be paid for ‘from the proceeds of growth’ should not obscure the fact that lower tax means, ultimately, lower spending than we would otherwise have had. In the meantime, if there really are no plans to cut spending in line with the cut in taxes then it would mean higher government borrowing.

As a result, some of the critiques that Mr Sunak has so far levelled at Ms Truss’ plans now also apply to his own - though, importantly, still to a considerably smaller degree: Ms Truss’ tax cut proposals come to more than £30bn per year (possibly a lot more) while Mr Sunak’s come to £19bn. Both face questions about how permanent tax cuts would be paid for given the long-term demands on public spending arising from an ageing population, climate change, geopolitical risks, and so on. The OBR’s recent Fiscal Risks and Sustainability report raises questions about the long-run sustainability of the public finances given those pressures even under existing plans, let alone with substantial tax cuts as well. If the two candidates want a smaller state than current plans imply, it would be good to see more openness about the implications for spending and some sense of what would be cut back, not just which taxes they would like to reduce.

Ms Truss’s proposed tax cuts remain much larger than Mr Sunak’s. That is largely because she wants to cancel the large rise in corporation tax that is currently planned for next April. On personal taxes - timings aside - there is a strong similarity between Mr Sunak’s proposal to cut income tax by 3ppts and Ms Truss’s proposal to cut National Insurance contributions (NICs) by 2½ppts. But there are also some differences:

- Mr Sunak’s cuts in income tax would go directly to individuals, whereas Ms Truss’s cut to NIC would initially be shared roughly 50:50 between employers and employees, although in the long term we would expect wages to adjust so that the effect of cutting taxes on employers and employees would be similar.

- Mr Sunak’s cut to income tax is only to the basic rate - it would apply only to income up to the higher-rate threshold (though higher-rate taxpayers would also gain from a tax cut on that part of their income) - whereas Mr Truss’s cut to NICs would apply to earnings above that level as well.

- Cutting NICs would reduce taxes only on income from employment and self-employment, whereas cutting income tax would also benefit people with other sources of income such as pensions and property.

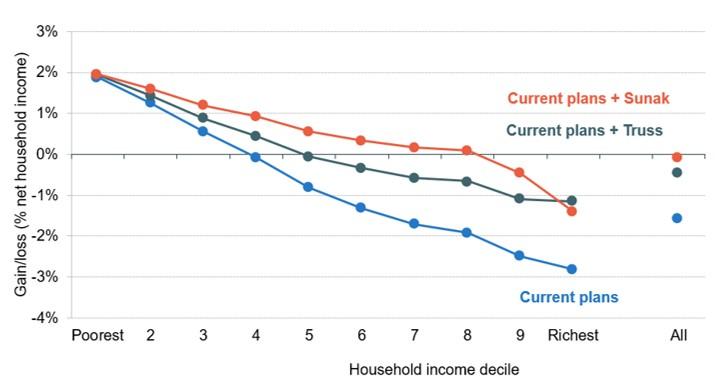

Figure 1 shows the net effect of these proposals in the context of the permanent reforms the government has already implemented or announced this parliament. The policies already announced are clearly progressive, with increases to benefits (most importantly the cut to the universal credit taper rate) boosting incomes at the bottom of the distribution and increases to taxes (both the rise in the NICs rate and the freezing of income tax thresholds) reducing incomes at the top. Both Mr Sunak’s and Ms Truss’s tax cuts would primarily benefit higher-income households, though still leaving the overall policy package a progressive one when combined with reforms to date. Mr Sunak’s reform would raise incomes by more than Ms Truss’s for the bottom 90% of the distribution, on average - largely reflecting the fact that it is simply a bigger tax cut. Among the richest 10% of households Ms Truss’ reform would do slightly more to boost incomes - a consequence of the fact that Ms Truss’s reforms would reduce the tax rate on earnings above the higher-rate threshold while Mr Sunak’s wouldn’t.

In addition to this, note that Ms Truss has also expressed a desire to introduce another (potentially multi-billion pound) cut to personal taxes for families, perhaps by making the income tax personal allowance (rather than just 10% of it, as now) transferable between spouses and civil partners. She has not, however, made a firm commitment to doing this.

Figure 1. Impact of permanent changes to the personal tax and benefit system since April 2019

Note: The ‘current plans’ line includes policy already implemented this parliament, as well as the government’s existing plans for future reforms. It includes freezes to income tax thresholds, the rise then freeze to the NICs primary threshold, 1p cut to the basic rate of income tax, cut to the universal credit taper rate and increase in work allowances, increases in local housing allowance rates, freezes to fuel and alcohol duties, and the introduction of the health and social care levy. ‘Current plans + Truss’ adds the removal of the health and social care levy (and assumes the removal of the employer contribution would be passed on to employees in higher wages), while ‘Current plans + Sunak’ adds the reduction of the basic rate of income tax by a further 3p.

Source: IFS analysis using the IFS tax and benefit microsimulation model, TAXBEN, run on uprated data from the Family Resources Survey and the Living Costs and Food Survey.