At the Spending Review on 27 October, the Chancellor faces a dilemma. He has announced a £14 billion top-up to his March 2021 spending plans, alongside a manifesto-breaking tax rise. Overall funding for public services is planned to increase at a faster rate than at Labour’s 2007 Spending Review. Rishi Sunak, a Conservative Chancellor, is set to oversee a lasting increase in the size of the state of around 2% of national income. But still he faces an unpalatable set of spending choices.

In this chapter, we look at the options and trade-offs for the Chancellor ahead of the forthcoming Spending Review. We outline the framework used for planning public spending, trends in departmental spending since 2010, and some of the key areas where the Chancellor will be under pressure to allocate additional funds. These include public services disrupted by the pandemic – most notably the NHS – but also public sector pay awards, social security, and the government’s stated policy priorities (such as social care reform, levelling up and net zero). We then turn to an analysis of the Chancellor’s latest spending plans, fixed on 7 September, and what these imply for different areas.

The conclusion is that this Spending Review still promises to be a tricky one. There are no easy options, but the decisions made will be of major economic, fiscal and political importance.

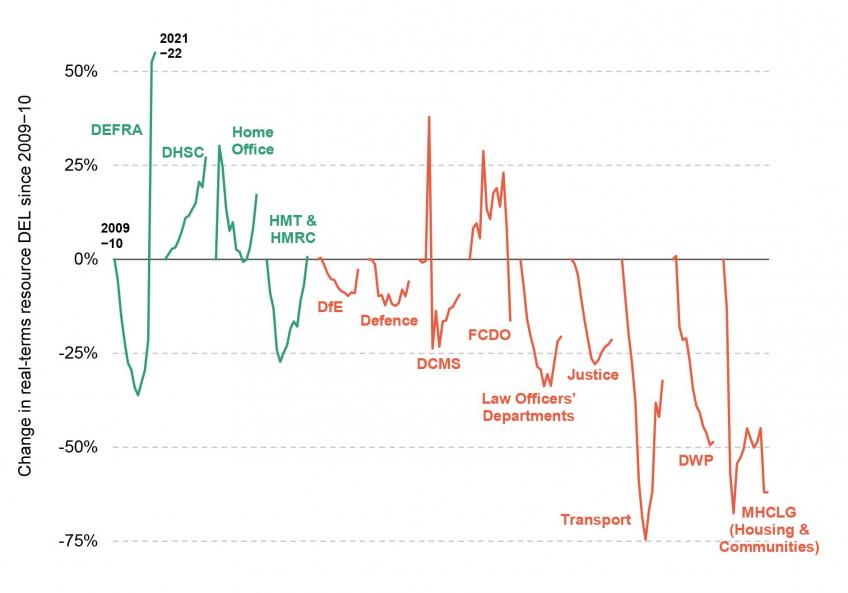

Figure 1. Percentage change in departmental ‘core’ (non-virus) resource budgets, 2009−10 to 2021−22

Notes and sources: see Figure 5.4 of IFS Green Budget 2021.

Key findings

- At the Spending Review on 27 October, the Chancellor faces a dilemma. He has announced a £14 billion top-up to his March 2021 spending plans, alongside a manifesto-breaking increase in National Insurance contributions. Overall funding for public services is planned to increase at a faster rate than at Labour’s 2007 Spending Review. Rishi Sunak, a Conservative Chancellor, is set to oversee a lasting increase in the size of the state of around 2% of national income. But still he faces an unpalatable set of spending choices.

- The latest overall spending envelope, set and published in early September, is more generous than those previously pencilled in at the March 2021 Budget, but still marginally less generous (around £3 billion lower in 2024−25) than those published in March 2020. In other words, despite the substantial pressures placed on public services by the pandemic, the Chancellor is planning to spend no more overall than he was prior to COVID-19.

- These plans imply a tight settlement for many areas of government over the next two years. Sticking to them would mean overall public service funding increasing year on year, but would require cuts to unprotected budgets (which include local government, prisons, further education and courts) of more than £2 billion in 2022−23. This could be difficult to reconcile with the government’s promises on levelling up and social care reform. The Chancellor’s plans imply more wiggle room in the medium term: funding for unprotected budgets is set to grow by more than 8% in 2024−25, the final year of the Spending Review period, after real-terms cuts over the previous two. Mr Sunak might consider bringing some of that funding forward to the next two years, when pandemic-related pressures on departments are likely to be at their most acute. If he wished, he could do so without spending any more overall.

- In reality, an ever-growing NHS budget and top-ups needed elsewhere will likely eat into the amount available for unprotected budgets in 2024−25. Plugging a possible £5 billion shortfall in the NHS budget in 2024−25, plus an extra £4 billion or so to return overseas aid spending to 0.7% of national income (which the government claims to be committed to), would be more than enough to require further real-terms cuts to unprotected budgets in that year. A difficult two years for areas such as local government and justice could very easily become a difficult three.

- Most of the unprotected budgets facing potential cuts under the Chancellor’s current plans were cut hard through the 2010s. For instance, despite recent increases in the day-to-day budget for the Ministry of Justice and the Law Officers’ Departments (which includes the Crown Prosecution Service), core spending in 2021−22 for each is still set to be 21% lower in real terms than in 2009−10. Meanwhile, health spending has risen steadily, and is set to account for an ever-growing share of day-to-day public service spending: 44% by 2024−25, up from 42% in 2019−20, 32% in 2009−10 and 27% in 1999−2000.

- The Chancellor’s plans allow for additional spending to deal with pandemic-related pressures on the NHS, but make no allowance for virus-related spending on other services. COVID-19 pressures on other parts of the public sector will not simply dissipate after this year: ongoing support for public transport operators and a catch-up package for schools could easily require £3 billion of extra spending each year. The Chancellor should be prepared to make additional funding available via a ‘COVID-19 Reserve’, but is right to set out spending plans of individual departments for the remainder of the parliament. After sensibly following the advice in last year’s Green Budget to set budgets for only one year in the 2020 Spending Review, now is the time to return to the certainty and stability of multi-year budgeting, while retaining the flexibility to respond to changing conditions.

- Many public sector workers – particularly those who are more experienced and higher earning – are still earning substantially less than their equivalents in the past. For instance, pay levels for experienced teachers in 2021 are 8% lower in real terms than in 2007, and average real-terms pay for NHS dentists fell by more than a third between 2006–07 and 2019–20. More generally, during the sustained period of public sector pay restraint in the years after 2010, pay awards in the public sector failed to keep pace with private sector pay growth. But over the past two years, average public and private sector earnings have grown at roughly the same rate. The Spending Review will not make direct public sector pay awards, but could provide an indication of future pay policy – including whether the pay freeze for most public sector workers will come to an end next year. There was some logic to the public sector pay freeze in 2021, but extending it risks having a damaging effect on recruitment, retention and motivation.