Today the Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies (SAGE) published its latest paper, Direct and Indirect Health Impacts of Covid-19, featuring contributions from the Institute for Fiscal Studies and Imperial College London. This paper, discussed by SAGE on the 9th September, retrospectively examines the impacts and mechanisms of the pandemic on the health of the UK’s population.

In collaboration with the Department for Health and Social Care, we produced detailed estimates of the disruption to NHS hospital activity in England during the first year of the pandemic (March 2020 – February 2021). This builds upon previous analysis that showed significant disruptions to inpatient and outpatient activity during the first ten months. And while aggregate statistics show that activity at the national level has remained disrupted even up to July 2021, the use of individual-level hospital data (available with only a much longer time lag) has enabled us to examine in far greater detail which services have been most disrupted and who has been most affected.

In January and February 2021, during the midst of the second Covid wave, there were 33.7% fewer elective admissions, 26.0% fewer non-primary-COVID emergency admissions and 17.7% fewer outpatient appointments compared to the same period in 2020. This is broadly in line with the average falls in activity over the entire first year of the pandemic, but substantially smaller than the disruption seen in April and May 2020 during the initial wave of the pandemic. This is despite there being more than twice as many patients admitted to hospital from treatment for COVID in January and February 2021 than in the first two full months of the pandemic. This suggests that either patients were more likely to come forward for care during the second wave, or hospitals were better able to provide non-COVID care along treatment for acutely sick COVID patients during the later period, or both.

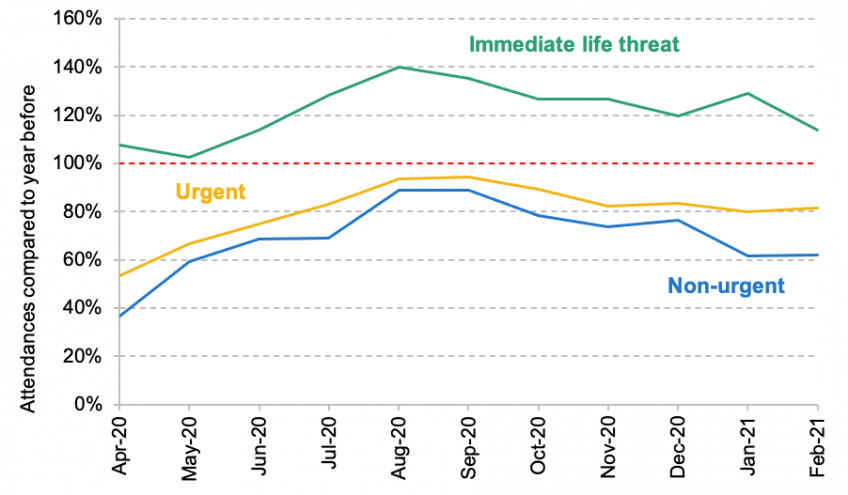

In addition to outpatient and inpatient activity, use of Accident and Emergency (A&E) services were significantly lower during the pandemic compared to the previous year. A&E attendances were 27.1% lower between April 2020 and February 2021 than the same period the year before. This reduction was likely due a number of factors: some patients may have avoided seeking care due to concerns about catching COVID-19 in hospital or overburdening the NHS, while there was likely also a genuine reduction in the need for emergency care.

However, the volume of patients arriving to A&E with an ‘immediate threat to life’ increased by 20.8% during this period (see Figure 1), from 202,000 between April 2019 and February 2020 to 244,000 between April 2020 and February 2021. This includes patients in cardiac arrest, respiratory and major trauma. Some of this may be accounted for directly by COVID-19 patients, but the timing does not match the waves of COVID hospitalisations. These additional urgent presentations may therefore in part be a consequence of missed care elsewhere in the NHS. However, it is important to note that the conditional probability of admission for patients in this category (which is assigned to patients upon arrival and before treatment) has also fallen – from 53.3% pre-pandemic to 41.7%, as well as the probability of dying in A&E. This is likely to reflect changes in the severity of patients even within this category of acutely sick patients, and requires further investigation to fully understand how A&E attendances and admissions have evolved during the pandemic.

Figure 1. Weekly A&E attendances compared to the year before

Source and note: See Figure 65 of the full SAGE report. Patients are classified upon arrival at A&E.

The report also highlights significant variation in the disruption of different services across different groups during the first year of the pandemic:

- There was significant regional variation in reductions in hospital activity, with the North and Midlands experiencing bigger reductions in hospital activity than the South and East of England. For example, elective admissions fell by nearly 38.5% in the East Midlands compared to a fall of ‘just’ 29.9% in the South West. These differences could be driven by a range of factors, including differences in the number of COVID cases in the local area, the underlying health of the local population and the amount of hospital capacity available in the local area prior to the pandemic.

- Reductions in volumes of care varied substantially across clinical specialties. Paediatrics saw the largest reduction in emergency admissions (42%) compared with the same period the year before. There were 59% (409,000) fewer trauma and orthopaedics elective admissions compared with a reduction of only 7% (58,000) for nephrology (treatment for kidney diseases, including dialysis).

- More deprived areas experienced larger reductions in emergency admissions than less deprived areas. For example, the most deprived fifth of local areas saw a reduction in emergency admissions 12.7% bigger than the fall in the least deprived areas (25.7% compared to 22.8%). However, there was very little difference in the percentage falls for elective admissions and outpatient appointments between more and less deprived areas.

- There were substantial differences in changes in hospital activity by ethnicity. White British individuals had a 36.9% reduction in elective admissions, compared with 35.8% for Asian individuals and 26.8% for black individuals. For emergency admissions, white British individuals saw a 23.2% decline, compared with 34.7% for Asian individuals and 29.7% for black individuals.

The substantial disruption to hospital activity over this period will cause a number of challenges for the NHS going forward. The reduction in elective and outpatient activity will almost inevitably lead to big increases in waiting lists in future, as patients return for treatment that they have missed over this period. This will be exacerbated further by any delays in the return to full NHS capacity as a result of the ongoing need for infection control and COVID-related staff absences

Changes in both emergency and elective care also risk creating or widening pre-existing health inequalities across groups. Understanding who has lost care, and the consequences this may have for future health outcomes, is therefore a crucial part of recovery from the pandemic.