By the time children return to school in September, most will have spent more than a staggering five months out of school. Such prolonged time out of school risks setting back children’s learning and development. This is particularly concerning for children from disadvantaged backgrounds, who already achieve less well on average than their better-off classmates and whose parents are at greater risk of losing their jobs as a result of the crisis.

Many studies – from our team but also from the Centre for Longitudinal Studies, the Sutton Trust and the National Foundation for Educational Research among others – have shown that children from different backgrounds have indeed had a very unequal experience of home learning. But gaps in home environments existed before the crisis, so is this evidence sufficient to suggest that the crisis will exacerbate existing inequalities in children’s attainment? If so, are there any lessons we can draw from our first lockdown experience to help mitigate the impact of the crisis on inequalities and ‘level up’ children’s remote learning experiences, should schools need to close again because of a spike in COVID-19 cases?

Our new research, funded by the Nuffield Foundation and released today, attempts to address these questions. It is based on bespoke survey data we collected on around 5,500 parents of school-aged children in England, who mainly responded in the first two weeks of May this year. We asked parents how they and their children spent each hour of what would have been a normal school day. We then compared time use during the lockdown with data from before the crisis, which come from the 2014–15 UK Time Use Survey. While these two data sets do not cover the same children, we can still explore how average learning time compares between these two periods and how any changes differ for children from poorer and better-off families. This observation highlights some of our key findings.

Learning time has gone down and become more unequal

Learning time was dramatically lower during the lockdown than prior to it. On average, primary school students spent 4.5 hours learning on a typical school day during the lockdown, down from 6.0 hours before the lockdown (25% reduction). For secondary schools, the absolute and proportionate drops are even larger, from 6.6 hours a day before the lockdown to 4.5 hours a day during the lockdown (32% reduction).

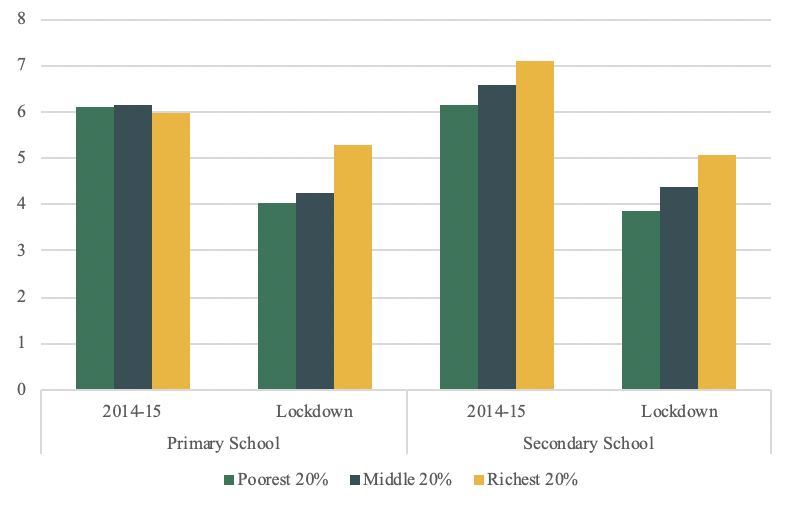

Learning time has also become more unequal, especially at primary school. Figure 1 shows the changes in total daily learning time, including both time in class and time on other educational activities, during a typical term week between 2014–15 and the lockdown period. It compares children from the poorest, middle and richest fifth of households (in the case of the 2020 data, based on their pre-pandemic earnings).

For primary school children, the lockdown has created new inequalities in learning time. Before the pandemic, there was essentially no difference between the time that children from the poorest and richest households spent on educational activities. But, during the lockdown, learning time fell by less among primary school children from the richest families than among their less well-off peers. The end result is that, during the lockdown, the richest students spent 75 minutes a day longer on educational activities than their peers in the poorest families – an extra 31% of learning time.

At secondary school, though, the picture looks very different. While the size of the gap between children from the poorest and the richest households during the lockdown, at 73 minutes a day, is almost precisely the same size as the gap for primary students, this inequality has much deeper roots; even before the lockdown, secondary school pupils from the richest fifth of families spent almost an hour a day more time on education than their worst-off peers. And, unlike at primary school, this is not just a story about the rich and the rest; the inequalities between the middle and the bottom are just as pronounced as those between the middle and the top.

Existing research has shown that extra learning time leads to better educational outcomes. The widening of the socio-economic learning-time gap during the lockdown therefore suggests that the lockdown could worsen educational inequalities between children from poorer and richer backgrounds, especially among primary school students.

Figure 1. Change in total learning time between 2014 and 2020 lockdown, by family earnings

Note: Poorest, middle and richest groups are based on equivalised family earnings (based on pre-pandemic earnings for lockdown data).

Source: Authors’ calculations using data from the 2014–15 UK Time Use Survey and the IFS–IOE survey of time use during COVID.

Access to learning resources is also unequal

Of course, how much time children spend on educational activities is not the only factor that will determine the effect of the crisis on educational outcomes. Among other factors, the quality of the home learning environment and of the resources children receive from their schools are likely to matter for how well and how much children learn during that time. Differences in access to such resources during lockdown between children from poorer and better-off families could also exacerbate existing inequalities in children’s attainment.

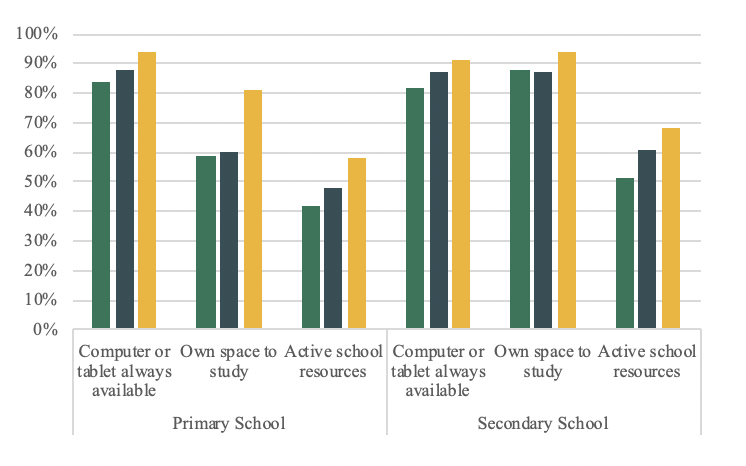

Figure 2 shows the percentage of students in primary and secondary school from the poorest, middle and richest fifths of families who have a computer/tablet available to use as needed, their own space to study and access to active learning support by their school (which includes online classes, video conferences or online chats with a teacher).

A large majority of primary and secondary school children from all earnings groups had a computer or tablet always available, with those in the richest fifth 9–10 percentage points more likely to have access than those in the poorest fifth. Better-off children are also more likely to have their own study space, as opposed to having no space at all. This inequality is particularly marked for primary school children, where the richest fifth are 22 percentage points more likely to have space than the poorest.

Resources provided by schools are also unequally distributed. Around 42% of the poorest fifth of students in primary school received some sort of active learning support from their school, compared with 58% of the richest fifth. A similar gap exists for secondary school pupils, with 51% of the poorest fifth of pupils getting some sort of active resource compared with 68% of the richest fifth.

Figure 2. Access to learning resources, by family earnings

Note: ‘Computer/tablet always available’ measures whether the student has access as needed to a computer or a tablet to do their schoolwork. ‘Own space to study’ measures whether the student has access to a dedicated study space at home. ‘Active school resources’ measures whether a student’s school offers online classes, videoconferencing or online chats with a teacher.

Source: Authors’ calculations using data from the IFS–IOE survey of time use during COVID.

Are inequalities in learning time explained by unequal access to learning resources?

The socio-economic inequalities in learning resources that we have documented could contribute towards the effect of school closures on attainment gaps for at least two reasons. First, better learning resources could help children learn more during the time that they spend on educational activities. Second, better resources could also make learning more appealing and enjoyable, thus encouraging children to spend more time learning.

While we are not able to test the first hypothesis in our data, we do find evidence suggestive of the second one – children who have better access to learning resources are also likely to spend more time learning than children who do not. This fact, combined with the fact that better-off children are more likely to have access to those resources, suggests that at least some of the differences in learning time could in part be driven by differences in access to resources.

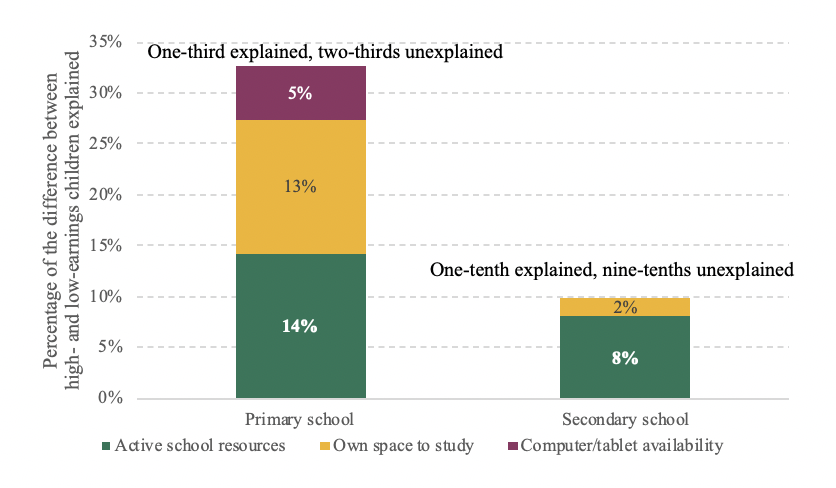

Figure 3 investigates this empirically. This analysis shows that socio-economic gaps in the learning resources that we have focused on – study space, computer/tablet access and active school resources – explain at most a third of the learning-time gap between poorer and richer primary school students. Among secondary school students, they explain at most a tenth of the gap.

Figure 3. Share of inequalities in total time explained by home and school resources

Note: ‘Active school resources’ measures whether a student’s school offers online classes, videoconferencing or online chats with a teacher. ‘Own space to study’ measures whether the student has access to a dedicated study space at home, whether shared or not. ‘Computer/tablet availability’ measures whether the student has access as needed to a computer or a tablet to do their schoolwork. Results are based on a decomposition of socio-economic inequalities in total learning time based on inequalities in these three factors, using the methodology proposed by Gelbach (2016).

Source: Authors’ calculations using data from the IFS–IOE survey of time use during COVID. Based on table 7 of the accompanying working paper.

This means that if the goal is to ‘level up’ children’s home learning experiences, it is worth paying attention to schools, homes and technology. But ‘levelling up’ these aspects of children’s home learning experiences can only go some way towards getting poorer students to study as much as those who are better-off. For secondary school students especially, it could not go very far at all. This is perhaps unsurprising in light of the magnitude of inequalities in learning time among them that already existed prior to the pandemic hitting.

Conclusions

While all pupils in England are expected to return to full-time schooling next month, according to our findings there is a real risk that time spent learning at home since schools closed in March has widened educational inequalities between poorer and richer students, especially among primary school students.

The ongoing risk of local or national spikes in COVID-19 cases means that pupils may not have seen the last of home learning. If the pandemic forces schools to close again, it will continue particularly to deprive poorer students of the protective and (at least partly) equalising role that time in school can play for their learning and development.

The types of home learning support that the policy debate has focused on so far are important, but our findings strongly suggest that it would take more than better home learning resources to prevent poorer students from falling behind. Appropriate support will require a better understanding of the wide-ranging effects of this shock on families and the complex ways in which these interact with pre-existing inequalities in family circumstances.