The long awaited 2019 Spending Review has finally been timetabled. HM Treasury has announced that it will set departmental budgets for the coming financial year, 2020−21, in September. A full multi-year spending review has been pushed back to 2020. If the new Chancellor wants to avoid making further cuts to any department’s day-to-day spending budget in 2020–21 then he will need to top up the provision spending plans he has inherited from his predecessor by at least £2 billion in that year.

The ongoing uncertainty surrounding the nature of the UK’s departure from, and future relationship with, the European Union means that the outlook for the UK economy is currently highly uncertain. Given that, setting departmental budgets for just one year is understandable, and leaves the Government more flexibility to respond to future developments. While departments crave multi-year spending settlements for future planning, such plans in the current climate would probably have lacked credibility.

Why, though, one would decide on that settlement before the nature of Brexit is known is rather unclear. Why not wait until November and make the allocations alongside other Budget decisions? The public finances and the wider economy will be profoundly affected by the Brexit outcome. It would make sense to wait until you have the latest economic and fiscal forecasts before you decide how much you want to spend – not to mention decide how you’re going to change taxes and/or borrowing to pay for it.

What do we know already?

So what do we know about the likely contents of this spending review? There are already a number of commitments which the spending review will need to provide for. Even before the recent change in Prime Minister these included a five-year settlement for day-to-day spending on the English NHS worth more than £20 billion in real terms by 2023−24, as well as a commitment to spend (at least) 2% of national income on defence and 0.7% on overseas aid. The new Prime Minister has also promised to provide additional funding for English schools and to recruit 20,000 new police officers in the coming years.

Reversing all cuts to per-pupil schools spending since 2009−10 and protecting it from cuts going forwards would cost around £5 billion by 2022−23; recruiting 20,000 police officers by 2021−22 would cost in the region of £1 billion. So to be on track to deliver those promises, the Chancellor would need to provide more than £2 billion extra to those areas next year.

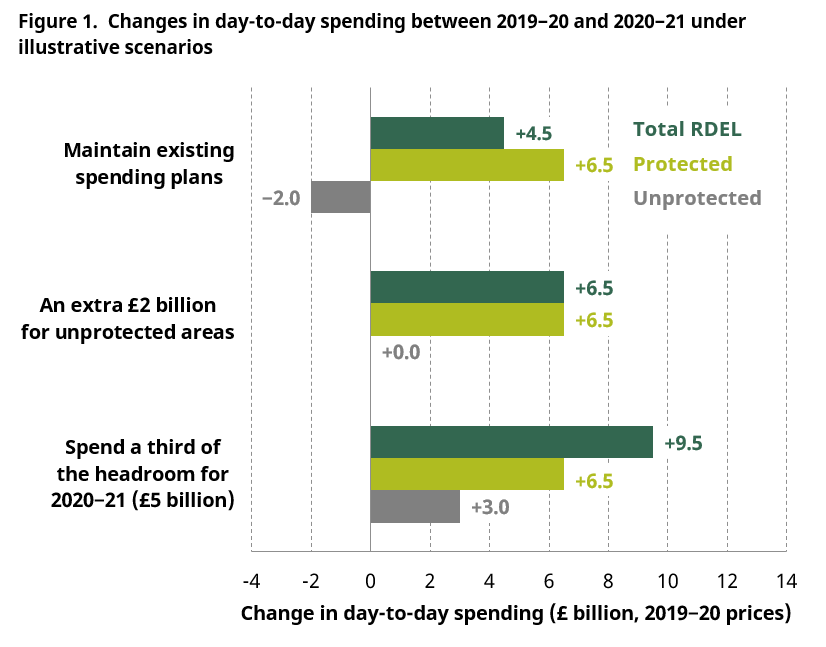

Ahead of the spending review, though, we still don’t know how much the government plans to spend overall. It is to be presumed that overall spending will be promised at a level above that implied by the provisional spending plans published by the previous Chancellor Philip Hammond alongside the March 2019 Spring Statement. Those plans imply an increase in day-to-day spending of £4.5 billion (1.5%) next year, in 2019−20 prices. If these were in fact adhered to, then taken together with the government’s commitments on the NHS, defence, overseas aid, schools and the police, these would imply cuts to the other ‘unprotected’ areas of around £2 billion next year (as is illustrated by the top three bars in Figure 1).

Note: RDEL refers to resource departmental expenditure limits. Protected spending includes the NHS, defence, overseas aid, police and schools. In the third scenario, all or some of the £3 billion for unprotected could instead be allocated to protected departments.

Source: Authors’ calculations using OBR Economic and Fiscal Outlook March 2019 and HM Treasury Public Expenditure Analyses, July 2019.

The Chancellor may decide to spend more

Sticking to existing plans, however, does not appear to be a likely scenario. All sounds emanating from Numbers 10 and 11 Downing Street point towards an increase in overall spending relative to existing plans. A top-up of £2 billion in 2020−21 would be sufficient to deliver on the spending promises announced so far and avoid making real cuts to other areas next year (at least on average). The middle bars of Figure 1 shows that overall day-to-day spending (RDEL) would increase by £6.5 billion (2.1%) next year in this case.

The Chancellor could decide to spend more than that: he could increase borrowing by up to around £15 billion next year and remain on course to meet his fiscal mandate of having structural borrowing of less than 2% of national income. However, a £15 billion increase in spending seems unlikely – the Prime Minister also has stated ambitions to reduce taxes, and it seems prudent given the current economic uncertainty (and the fact that the spending review will report before the latest economic and fiscal forecasts are produced) to maintain some expected room for manoeuvre against the fiscal targets. Even £15 billion of “headroom” could vanish if the forecasts were substantially downgraded.

The Chancellor could choose to spend, say, a third of his £15 billion fiscal headroom for next year, boosting overall day-to-day spending by £5 billion over and above existing plans. That would mean a £9.5 billion (3.1%) real increase in day-to-day spending by central government on the provision of public services between 2019−20 and 2020−21. This would be sufficient to pay for the announced promises and freeze all other budgets in real terms, and would then leave a further £3 billion to be allocated as he sees fit. A £10 billion top-up would allow for a £14.5 billion (4.7%) real increase, and leave the Chancellor with £8 billion to spend after meeting his promises in priority areas and freezing all other budgets.

Even with increases at these levels real spending across a range of departments would remain well below their 2010 levels. For example, spending on justice, local government services and 16−18 further education are currently respectively 28%, 21% and 18% below 2010 levels so would require very large spending increases to reverse those cuts – increases it would be extremely unwise to try to implement in a single year.

A pause to austerity?

This spending review is likely to herald the end of austerity for public services – at least for next year. But the outlook – both for the economy and for public spending – remains highly uncertain. A disorderly ‘no-deal’ departure from the EU that causes short-term disruptions and permanent damage to the productive potential of the UK economy would, in the long term, mean lower incomes and less money available to spend on our public services. It is possible, therefore, that this year’s spending review will represent a pause, rather than an end, to austerity.