Collection

A full analysis was presented at a briefing on Wednesday 14 March 2018

Event materials

For those of you accustomed to our post Budget events, this one will be a little different to usual. That reflects that fact that yesterday’s Spring Statement lived down to its billing. It was not a fiscal event. And that’s a good thing. One fiscal event a year is more than plenty.

So rather than picking over the entrails of a non-event, what we will do today is put yesterday’s fiscal and economic numbers in the context of the last decade, and look forward to some of risks and challenges we might face over the next decade. This is after all, almost to the day, the tenth anniversary of the last pre crisis Budget. In March 2008 Alastair Darling presented forecasts suggesting the economy would grow at a healthy 2% a year, the deficit and debt would be steady, and things would carry on much as before. It was still possible for some to persuade themselves that the economic cycle of boom and bust had been abolished. There was no suggestion of the deepest recession since the 1920s, which in fact hit that autumn, let alone of a record deficit, a doubling of debt and a decade of slow economic growth, no earnings growth and apparently never-ending austerity.

The history matters. It matters in part because we should never stop reminding ourselves just what an astonishing decade we have just lived through, and continue to live through. The economy has broken UK record after UK record – record low earnings growth, record employment levels, record low interest rates, record low productivity growth, record cuts in public spending. It also matters because it sets the context for the challenges we still face.

And in that context what changes there were in yesterday’s forecasts barely register. But let’s start by looking at what we did learn, before setting out some of the longer term trends and the challenges that remain.

Spring Statement forecasts

Relative to what we were told in the Autumn Budget, nothing of importance changed. The deficit this year is projected to come in about £4 billion less than expected in the Autumn, and about £13 billion less than projected in the March 2017 Budget. That is good news, largely driven by better than expected tax receipts. That good news largely washes out over the next few years, however. The structural deficit in 2019-20 is almost unchanged. In part that’s because some of the tax receipts are just revenues brought forward. In part it’s because spending, notably on debt interest, is expected to rise a bit as interest rates rise faster. In part, it’s because the OBR now believes the economy to be operating slightly above capacity: slightly better economic growth in 2017 is offset by slightly worse growth later on.

That last point is worth dwelling on. We have had the worst decade of growth since at least the last War. The economy is at least £300 billion smaller than we might have expected based on 2008 forecasts. Yet we are now supposed to be at capacity, with no potential to make up for any of that loss.

What’s more, growth projections remain very subdued. At no point in the next five years does the OBR believe that annual growth will exceed 1.5%. To put an even less positive gloss on the numbers, growth in GDP per capita is forecast to be less than 1% in each of the next five years, half the pre-crisis trend.

Dismal productivity growth, dismal earnings growth and dismal economic growth are not just part of the history of the last decade, they appear to be the new normal.

One result of that is that while the deficit has returned to normal pre-crisis levels the accumulated debt is not forecast to fall to any significant degree. Once you strip out the effect of Bank of England transactions, debt as a fraction of national income is essentially flat from 2019 onwards. That’s partly down to slow growth. It’s also partly down to the way we account for student loans. The £20 billion or so paid out every year to cover the cost of higher education does not add at all to the deficit in the year it is made, but it does add fully to the debt (despite the fact some will be recouped). Furthermore interest charged on the outstanding stock of debt reduces borrowing as it accrues even though most of it will never be collected: in 2022–23 this is worth £7.5bn off the deficit. The upshot of all of this is that even with a deficit of zero in 2022–23 we would be adding around £30 billion to debt.

More on the future challenges in a minute. First, just a bit more reflection on the last decade.

The last decade

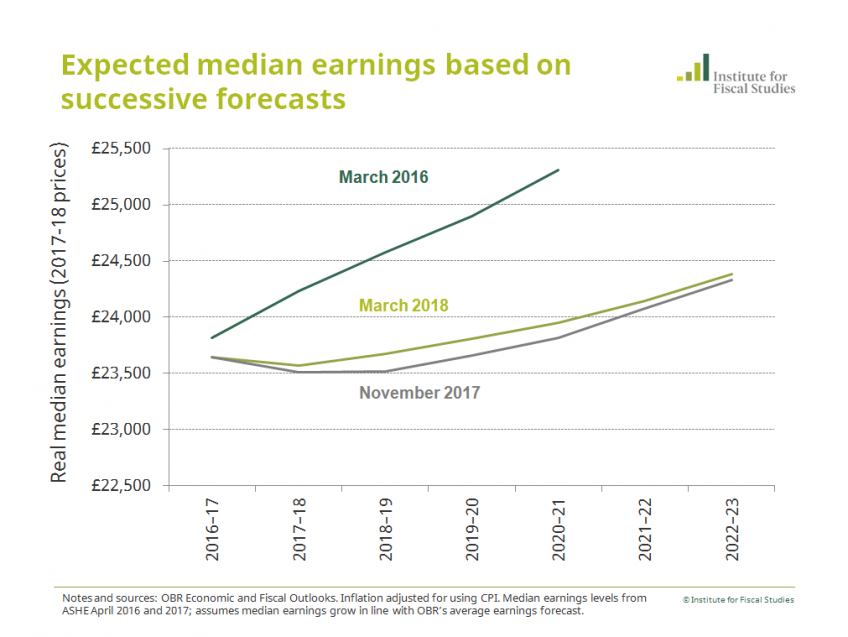

One could talk for hours about what has happened over the last decade. The ten years of growth since 2008 have been worse than any comparable period coming out of any recession since the 1920s. The economy is 14% smaller than might reasonably have been expected in 2008 based on pre-crisis trends, while national income per person is £5,900 lower compared to the same benchmark. Astonishingly, median earnings remain below their 2008 level.

The recession caused a huge spike in borrowing, taking it to a post war record 10% of national income. Much of the fiscal history since then has been about getting that borrowing down. After eight years of austerity it is now back to pre-crisis levels: just over 2% of national income. Debt, on the other hand, has reached more than twice its 2008 level.

Most of the deficit reduction has come courtesy of spending cuts rather than tax increases. The period since 2010 has been completely unprecedented in the scale of cuts imposed. But all those cuts have achieved is to return spending to its same level relative to national income as it was in 2007-08. All that pain just to get the size of the state back to pre crisis levels. This is a very important part of the history to understand.

The tax burden has risen a little, to what are now historically high levels. But the more interesting story with tax has been the combination of some very big tax cuts – to corporation tax, through increasing the income tax personal allowance – with some very big increases – the hike in VAT, and big increases in income tax paid by some of the richest.

Risks and challenges ahead

So we have been through a tough decade. Borrowing though is now down to pre crisis levels. To listen to the suddenly Tiggerish Mr Hammond you might think all was now well.

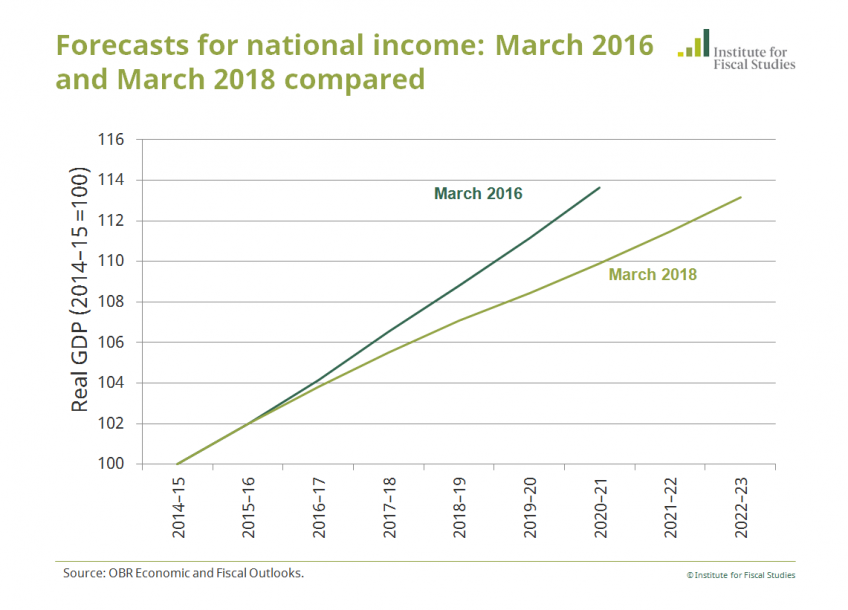

Well not so much. Growth prospects remain depressed, among the worst in the G20. And given the uncertainties around Brexit there remains plenty of risk on the downside. Economic and fiscal forecasts may not have changed much since the Autumn, but they are an awful lot worse than they were in March 2016. Debt may not be rising any more, but nor is it decisively falling. The OBR is projecting that productivity growth will return to 2% a year. But not until 2030. Earnings are still not projected to return to pre-crisis levels until the 2020s.

The big specific challenge facing the Chancellor though remains over how to balance growing demands for spending increases against his desire to balance the books in the mid 2020s. The fact that even on current plans debt is not really due to fall is likely to make him especially cautious about opening the spending taps. Yet the pressures are undeniable. Many of the public services are struggling in a way that they were not two or three years ago. Safety in prisons is being compromised. The NHS is visibly failing to cope as well as it was. Local government, having done a remarkable job of coping with cuts, is showing the strain. The cap on public sector pay may have been lifted, but we don’t know where the money to pay for any increases above 1% will come from. Further substantial cuts in the generosity of working age benefits have yet to take effect and so we have yet to see their consequences.

So what choices will Mr Hammond make in setting the envelope for the next spending review? He has promised to set it at the Autumn Budget and hinted that he would like to find more money.

Just to avoid spending falling as a fraction of national income beyond 2019–20 he would need to find an additional £14 billion a year, relative to current plans, by 2022-23.

On the other hand if he really wants to eliminate the deficit by the mid 2020s he would need to find an additional £18 billion or so of tax increases or spending cuts by the mid 2020s.

Put these two together and on current forecasts, just keeping spending constant as a fraction of national income beyond 2019–20 and reaching budget balance by the mid-2020s would require tax rises of £30 billion a year.

And that’s before additional demographic pressures which could add another £11 billion a year to the money the government would need to find from somewhere in 2025 if it wants to cover the additional demands for health, pension and social care spending.

Yet Mr Hammond also faces challenges on the tax side. He has been unable to tackle the problems posed by the increasing numbers of self employed and company owner managers, who pay less tax than similarly remunerated employees: the cost of this is forecast to grow from a bit over £10 billion now to around £15 billion or so in five years time. He – like his predecessor – looks wholly unable to maintain the real value of fuel duties. By taking huge numbers of people out of the income tax net, while raising tax on those with the highest incomes, we have become very dependent on a very small number of taxpayers to pay a very large fraction of the overall tax bill. That may be desirable on distributional grounds, but it makes tax revenues very sensitive to the incomes and behaviour of a small number of people. If high paid jobs (and EU citizens, who are well represented among high earners in the UK) relocate elsewhere the consequences for the Exchequer will be severe.

Consultations

Which brings us finally to what this Spring Statement did not really deliver on – the promise of consultations on longer term fiscal challenges. There are some welcome consultations on the details of a number of taxes, but nothing remotely addressing the kinds of challenges I have just enumerated.

Perhaps the most interesting of the consultations that there are relates to the challenge of how to raise tax from the digital economy. At present, the international norm is to try to allocate business profits to the countries in which value is created. This is already tricky. There has been much concern about how multinationals can shift profits out of high tax countries and away from where value is perceived to be created. The government’s current concern is that we’re getting the allocation of taxable profits even more wrong than we thought because we don’t account for the fact that, for some businesses, value creation is intimately linked to ‘users’. For example, users of digital platforms may directly generate content, such as social media posts or videos, which in turn attracts other users and is the basis upon which advertising revenues are generated. Users may also be generating value by providing data, for example on their preferences, or by being part of a network that underpins the success of a business model.

Effectively, the government thinks it should get a bigger slice of the global tax pie because lots of UK users are helping create value for digital businesses. Ultimately, the government would like to see the OECD play a leading role in reshaping international tax norms so that more taxable profits flowed to the countries in which the users of digital platforms are based.

Fair enough. We need to look at how our tax rules should deal with digital business models. But this is extremely difficult, not least because, even at a conceptual level, we don’t know how to assess the value created by users. And even if we could find practical ways to allocate profits based on user input, this would imply a reallocation of taxable profits away from some countries, including the US, and towards others, such as the UK. Getting general agreement on that will be challenging, to say the least.

In the meantime, the government is toying with the idea of an ‘interim revenue-based tax’. The UK could move unilaterally to raise some more revenue from tech giants but we shouldn’t expect this to represent a long term fix for business tax. It certainly won’t provide the kinds of revenues that would alleviate long term spending pressures.

In conclusion

Nothing much changed yesterday. The major news outlets have therefore given all this much less coverage than usual. Well it might not be news in the conventional sense. But the reality of the economic and fiscal challenges facing us ought to be at the very top of the news agenda. And I mean the reality, not the spin and bluster of politicians on all sides pretending there are easy solutions, that the promised land is just around the corner, or that they can reinvent the laws of economics. There aren’t. It isn’t. And they can’t.

1. Growth outlook much weaker than 2 years ago

“The growth forecast for 2018 has been revised up a little since November. But slightly weaker growth thereafter leaves the outlook for the economy in five years time broadly unchanged. Overall the forecasts are for subdued medium-term growth, with an economy that is more than 3% smaller in 2020–21 than was being forecast just two years ago.”

Thomas Pope, Research Economist

To be clear - against a long term trend of at least 2% a year growth, after poor growth since 2008, and compared with growth across rest of OECD, these are not encouraging forecasts https://t.co/UjoizmQWBI

— Paul Johnson (@PJTheEconomist) March 13, 2018

"Against a long term trend of at least 2% a year growth, after poor growth since 2008, and compared with growth across rest of OECD, these are not encouraging forecasts"

Paul Johnson, IFS Director

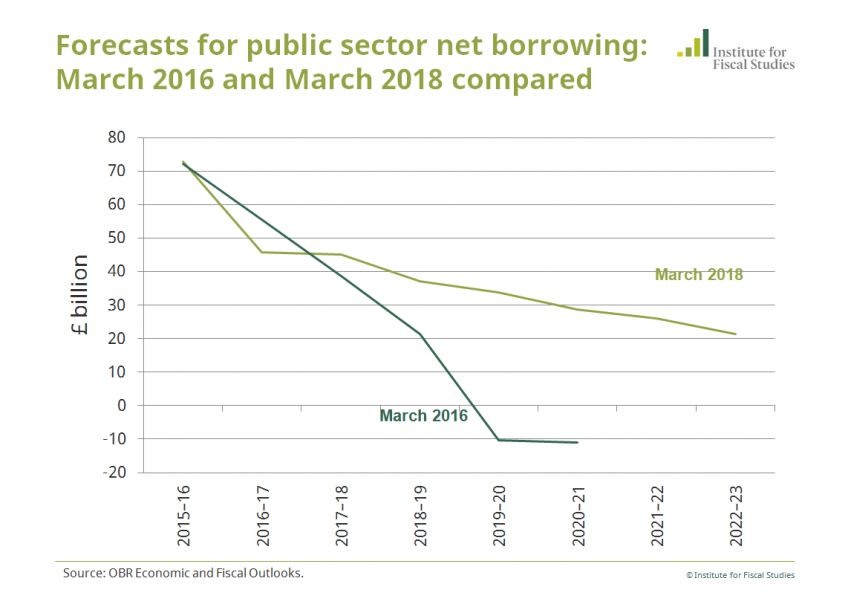

2. Forecast deficit much higher than 2 years ago

“The Chancellor revised down the forecast deficit for this fiscal year by almost £5 billion. This is good news and the deficit has been returned to pre-crisis levels. However the forecast for 2019–20 is for a £34 billion deficit, rather than the £10 billion surplus forecast just two years ago. The government now intends to eliminate the deficit by the mid-2020s, but even delivering that would entail difficult choices and missing it would certainly not be a surprise.”

Carl Emmerson, Deputy Director

3. Wage growth

"Despite a very marginal upgrade to the forecast for earnings growth today, real average earnings are now expected to grow by just 3.5% over the next 5 years, meaning their level in 2022-23 would be similar to 2007-08. Meanwhile inflation will continue to erode the value of most working-age benefits as they are frozen in cash terms, alongside other benefit cuts. Together this means we expect a further period of weak growth in the living standards of working age households." Robert Joyce, Associate Director

Collection details

- Publisher

- IFS

More from IFS

Understand this issue

Election Special: The UK economy since 2008

3 June 2024

Election Special: Your questions answered

27 June 2024

Election Special: The big issues politicians haven't spoken about

25 June 2024

Policy analysis

How do the last five years measure up on levelling up?

19 June 2024

The Conservatives and the Economy, 2010–24

3 June 2024

A decade and a half of historically poor growth has taken its toll

3 June 2024

Academic research

Do work search requirements work? Evidence from a UK reform targeting single parents

1 February 2023

The impact of area level mental health interventions on outcomes for secondary school pupils: Evidence from the HeadStart programme in England

13 October 2022

Prioritization, risk selection, and illness severity in a mixed health care system

16 June 2022