Collection

Independent, rigorous analysis from the 2020 Budget.

Spring Budget 2020: IFS analysis event (12/03/2020)

Videos and presentations

Introduction by Paul Johnson

The fiscal policy response to Covid-19 by Carl Emmerson

Borrowing to spend by Isabel Stockton

What does the Budget mean for public services? by Ben Zaranko

Slides from the event

The fiscal policy response to COVID 19 by Carl Emmerson

Borrowing to spend by Isabel Stockton

What does the Budget mean for public services? by Ben Zaranko

Permanent tax changes by Stuart Adam

Appendix - Distributional analysis by Tom Waters and Xiaowei Xu

Yesterday’s Budget was really two Budgets rolled into one. There was the normal Budget setting out medium term tax and spending plans. And then there was the emergency Budget aimed at dealing with immediate potential consequences of the coronavirus.

The latter made the former a rather odd affair. All the economic forecasts on which the core Budget was based were put together before any significant effect of the coronavirus was accounted for, and were therefore out of date at the moment of publication. If it turns out that the short term disruption caused by coronavirus is just that – short term – then all is well. Any significant longer term effect, though, and a smaller economy will mean the tax and spending plans set out yesterday will lead to an even bigger deficit than currently planned in the first few years of this decade.

So what are the headlines from these two budgets?

- The coronavirus package appears to be what was promised: timely, targeted and temporary. At £12 billion it is also substantial. It looks fairly well designed. It remains to be seen whether it will be enough to support public services, support the vulnerable and insulate the economy from long-term effects.

- The OBR’s economic forecasts are a little more positive than the Bank’s, but they are still very weak even before factoring in possible longer term effects from the coronavirus. Projected growth rates averaging barely over one and a half per cent a year for the next five years are feeble and indicative of an economy that is not in a robust position for coping with shocks like the coronavirus. The OBR continues to assume an orderly move to a free trade agreement with the EU. Anything less orderly, or a failure to achieve such an agreement, would weaken an already weak economy even further.

- Overall spending will rise by £76 billion or 9% in real terms between 2019-20 and 2023-24, largely paid for by extra borrowing. This will mean the size of the state, measured by looking at public spending as a fraction of national income, stabilising at nearly 41% of national income. That is above its pre-crisis level and bigger than at any point between the mid 1980s and the start of the financial crisis.

- The investment spending plans are genuinely very big. The intention is to get to the manifesto “ceiling” of 3% of national income in short order. This will take investment spending to its highest level in modern times. The challenge will be to ensure this money is well spent. That is a big challenge.

- The current spending plans are nothing like as generous as they appear. Average annual increases of 2.8% sound substantial. Take account of the need to replace EU funding, and factor in planned increases for health, schools, defence and overseas aid, and there is relatively little here for other departments. If this spending envelope is stuck to there are plenty of public services which will not be enjoying much in the way of spending increases over the next few years.

- Current spending plans also look suspiciously front-loaded. Spending increases pencilled in for the next two years are much bigger than what follows. This could suggest top ups in later budgets and hence a need for more tax or more borrowing.

- Current spending per person for most public services will remain well below 2010-11 levels in 2024-25. Chart 1.3 in the EFO shows current RDEL per person returning to 2010-11 levels. Outside of health though spending per person will still be 14% lower, and around 19% lower once you account for the spending that is simply replacing EU funding.

- On (pre-covid19) forecasts the Chancellor is on target to achieve a surplus on the current budget. There are clearly risks around this. There is a 40% chance that current budget balance will be missed and any significant long-term effect from the coronavirus, or from a failure to reach a trade deal with the EU, would certainly make this target much harder to hit.

- That still means borrowing peaking at £67 billion, nearly £30 billion above its 2018-19 level. With rising investment spending the current budget balance target is looser than the maximum 2% deficit targeted by Mr Hammond and far looser than Mr Osborne’s commitment for overall balance. Nevertheless, this appears entirely consistent with pre-election promises.

- Underlying debt is forecast to rise slightly relative to national income. If growth turns out less positive than expected as a result of coronavirus, Brexit or for any other reason, then debt could easily start moving decisively upwards.

Coronavirus package assessment

This is a substantial package well targeted at what it is seeking to achieve. It is, though, necessarily limited. On the business side it is aimed particularly at those businesses which might face a demand shock – those in hospitality, retail and so on. It does much less for those that might end up having to reduce production or close temporarily because staff can’t come into work either because they are ill, self isolating or looking after children who have been sent home from school. This may be a particular problem for manufacturing industry where home working will be much harder than in some office based jobs.

For individuals, there are many among the self-employed for example who won’t be helped by the Statutory Sick Pay changes. More generally, if this does lead to big temporary falls in income for some, the lack of financial resilience evidenced by very low levels of liquid savings may quickly create hardship including among groups who may not be entitled to benefits.

Mr Sunak will certainly want to monitor the effectiveness of the package and be ready to come back with more if necessary.

Public finances Assessment

Spending and borrowing are both rising over the next few years. They are doing so in a way which appears consistent with the Conservative manifesto, but which is different to the paths they were on under previous chancellors. Ever lower borrowing costs mean that this looks sustainable for now, but there are risks.

The first risk is that with a debt stock more than twice what it was pre crisis, with shorter maturities and a financing requirement much higher as a share of GDP than it was prior to the financial crisis, we are more vulnerable to changes in interest rates, inflation and growth.

Secondly, debt is not falling over a period in which growth seems to be at normal (if deeply disappointing) levels. It would grow sharply in the face of a downturn. This doesn’t look consistent with Mr Osborne’s mantra that the government should fix the roof while the sun is shining.

Most importantly, the current framework and set of policies do not look likely to deliver the kinds of spending growth that were implied in this budget speech. Outside of health and a few other protected areas it looks like little will be available to increase spending. Raising real day to day spending on public services will eventually require tax rises. Mr Sunak proudly announced that day-to-day departmental spending will enjoy “an average growth rate in real terms of 2.8% - twice as fast as the economy”. That is obviously not sustainable for any prolonged length of time. Importantly, while austerity is clearly at an end in the sense that spending is rising, spending levels in many areas are set to remain well below 2010 levels for a long time to come. Expectations may be disappointed.

Mr Sunak has promised a comprehensive review of the fiscal framework. That is to be welcomed. It doesn’t matter how hard you review it, though, the iron laws of fiscal arithmetic will assert themselves. The only way that a change in the fiscal rules can help justify more spending without tax rises is if the Chancellor is happy to see underlying debt rise more quickly.

One thing he should think hard about is the way in which the current framework favours capital spending. Not all capital spending is good. Not all current spending is bad. There is a risk that spending will be misallocated because there is so much more new capital to go around while current spending remains tight. These sorts of largely arbitrary distinctions can be costly.

Levelling up will require a great deal more than investing in capital projects. It will require a consistent industrial strategy, policy on education, local government spending and much more besides over a generation. More spending on roads and rail won’t change the fact that in the North East, for example, only 24% of working age adults are graduates while in London it is 47%.

Finally, reports that this Budget in some way accepts what Labour were proposing at the last election are very wide of the mark. While spending and borrowing are rising they are rising in line with Conservative manifesto promises, not in line with the far bigger numbers implied by the Labour manifesto.

Tax assessment

This was a tax raising budget overall, to the tune of just over £7 billion a year. This was largely driven by the reversal of the planned cut to corporation tax. It is fair to say that on taxes, as on investment spending and on planned borrowing, this budget did largely deliver on the, admittedly rather limited, manifesto promises.

In the round, though, the package of tax changes, looks piecemeal and it is not clear they are part of any long term thought through strategy. Mr Sunak has an opportunity in a second budget later this year to remedy that.

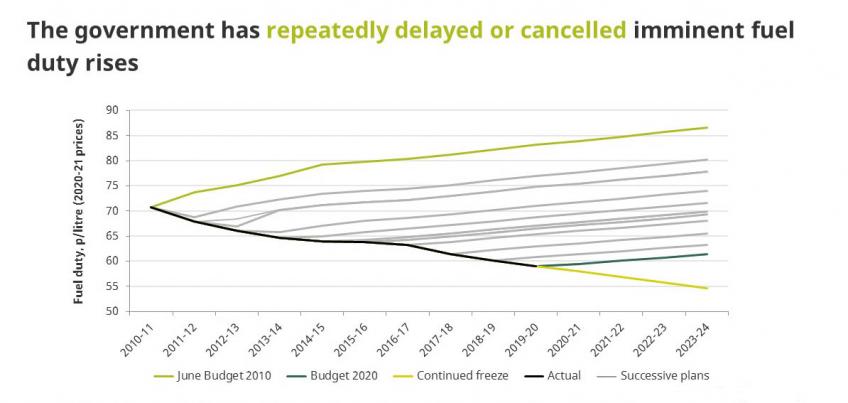

One area where a strategy is desperately required is on how to achieve “net zero”. A strategy is due later this year so perhaps a lack of direction this time round is forgivable, but the decisions made in this Budget don’t provide great confidence that the government is willing to grasp the nettle. The failure once again even to maintain the real value of fuel duties when oil prices are falling is not encouraging. Reducing the scope of “red diesel” is more encouraging, but allowing the relief to continue for farmers and some other users is not. Changes to the Climate Change Levy to recognise the role of gas use in greenhouse gas emissions makes sense. There is no sign of an appetite to tackle use of gas by households, though. We still have wildly different costs of carbon according to what fuel is used and by whom. Tackling this is surely a priority for the upcoming review.

The restriction to Entrepreneur’s relief to gains of £1 million is welcome, though it is a shame that this distortionary and unnecessary relief for the wealthy was not got rid of altogether.

The solution to the “doctors’ pension problem” was to push to the issue further up the income distribution. This means that far fewer people will be affected. But this remains a very poorly designed bit of policy. There remain a lot of fairly fundamental issues to be sorted out in the taxation of pensions, including: the much more generous treatment of defined benefit schemes relative to defined contribution, the excessively generous treatment by the National Insurance system, the very generous treatment of lump sums, and the absurd favouring of pension pots as a vehicle for inheritances. Again, a proper strategy would be nice.

Conclusions

Only time will tell whether any of the numbers in this budget will have meaning once the economic effects of coronavirus become fully evident. On the basis of the pre virus forecasts this was a budget that largely delivered on manifesto commitments. It will result in a big increase in borrowing. Investment spending is planned to rise quickly. Promised tax changes are being legislated.

There are plenty of risks and omissions lurking though. The bigger risks in the short term probably relate most to difficulties in spending the cash set aside for investment projects effectively, and in disappointing expectations on current spending. In the longer term higher borrowing and debt carry their own risks. The lack of any coherent strategy on tax is a long standing gripe. The lack of strategy on net zero will hopefully be sorted out later in the year, and a second budget will also give the new chancellor a chance to stake out his ground on tax.

As for the coronavirus response, this looks like a sensible package. Mr Sunak has promised to do whatever is needed, and more may be needed than promised here. If the long-term path of the economy is affected then he will also need to reassess much more of his fiscal strategy when he returns to the despatch box in the Autumn.

“This was a Budget in two parts.

First, in response to the coronavirus outbreak, the Government announced a £12 billion giveaway in the coming financial year including extra support for public services and tax cuts targeted at business that might be particularly hard hit by a fall in social spending.

Second, the Chancellor set the envelope for the coming Spending Review. Day-to-day spending is to rise, although much is simply to cover new post Brexit responsibilities. Genuinely striking is the substantial increase in planned capital spending. A key challenge will be to ensure that this money is spent well. The key risk is that once again growth disappoints, and that this leaves the Chancellor with the choice of whether to rein back again on spending, or to announce further tax rises, or to abandon his fiscal targets and to allow debt to rise further.”

Paul Johnson, Director, IFS

1. Borrowing

There has been a marked increase in the forecast for borrowing since the last official forecast, even before taking into account the economic and fiscal impact of the coronavirus outbreak.

2. Public spending

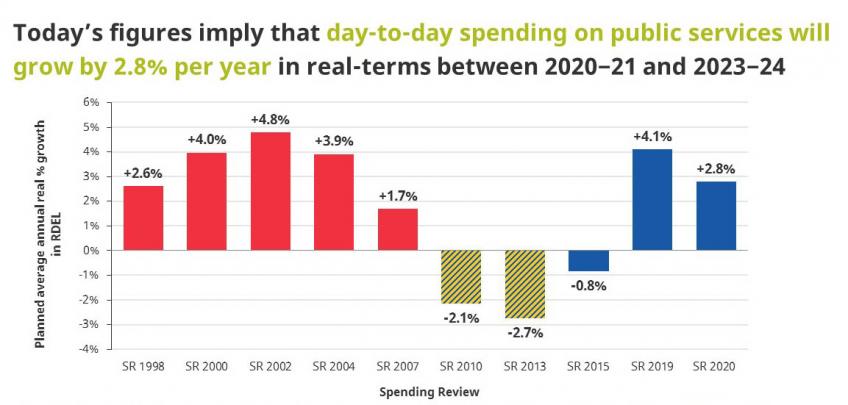

Public services will now get a sustained real-terms funding increase for the first time in a decade.

The 2.8% increases planned after next year are lower than the 4.1% increase for this year planned in the 2019 Spending Round, and considerably lower than under New Labour.

Note: Figures denote the planned average annual real growth rate in day-to-day spending on public services (Resource Departmental Expenditure Limits excluding depreciation). SR 2020 figures account for the OBR’s assumed underspend.

Source: IFS calculations using HM Treasury Spending Review (various), HM Treasury Budget 2020 and OBR’s March 2020 Economic and Fiscal Outlook.

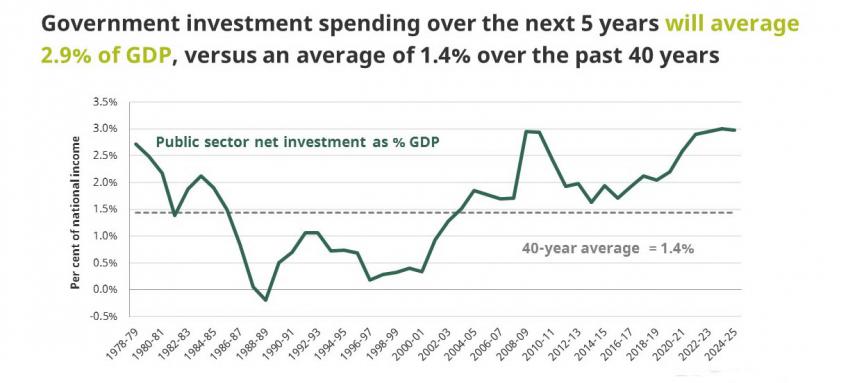

3. Investment spending

The Government plan to raise investment spending to 3% of national income by 2022, averaging 2.9% over the next 5 years.

If delivered and sustained, this will be double the average level seen over the past 40 years.

Source: IFS calculations using OBR public finances databank.

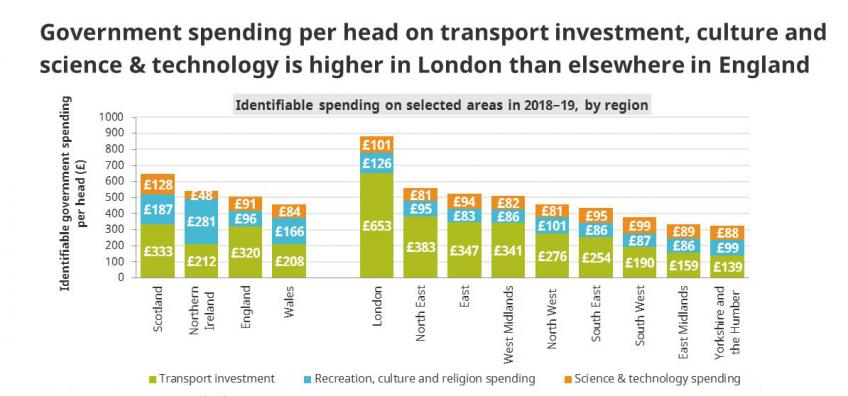

4. Levelling up

The Chancellor has reiterated the government’s commitment to ‘levelling up’ across the regions of the UK, with a review of the rules for which projects receive funding.

‘Levelling up’ will need to be about more than just transport however.

Note: ‘Transport investment’ denotes identifiable capital expenditure on transport. ‘Recreation, culture and religion spending’ and ‘Science & technology spending’ denote total (i.e. the sum of current and capital) identifiable expenditure on those areas.

Source: ‘Country and regional analysis: 2019’, ONS mid-year population estimates.

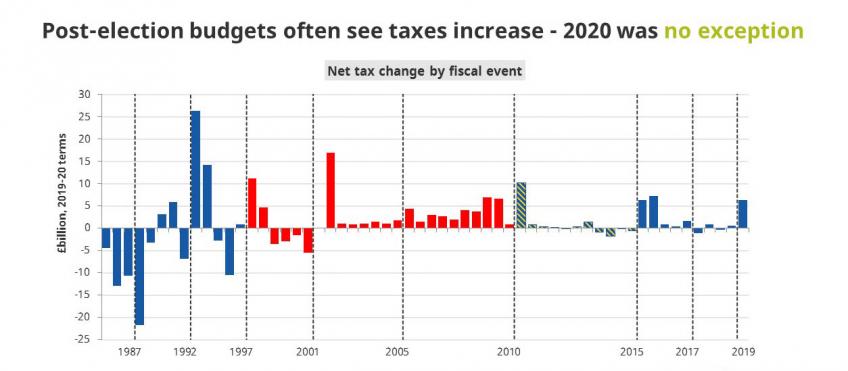

5. Tax increases

While the Chancellor announced short-term tax relief in response to the Coronavirus, Budget 2020 represents a long-term tax increase of over £6 billion a year.

This follows a long tradition of Chancellors announcing tax increases in the 12 months following an election.

6. Fuel duty

The government have again frozen fuel duty. The real value of fuel duty has fallen 18% since 2010, and by 30% relative to the plans the Coalition inherited.

Source: Updated calculations from Adam, S. and Waters, T., ‘Options for raising taxes’, in Emmerson, C., Farquharson, C. and Johnson, P., (eds), The IFS Green Budget: October 2018. Produced in association with Citi and ICAEW and with funding from the Nuffield Foundation.

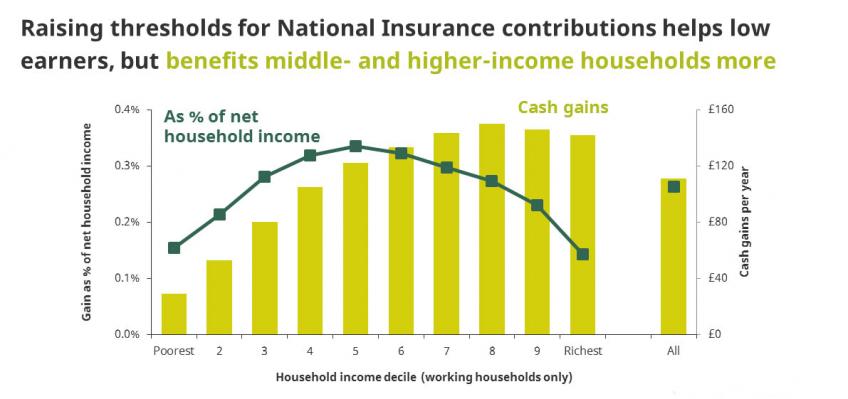

7. Supporting low earners

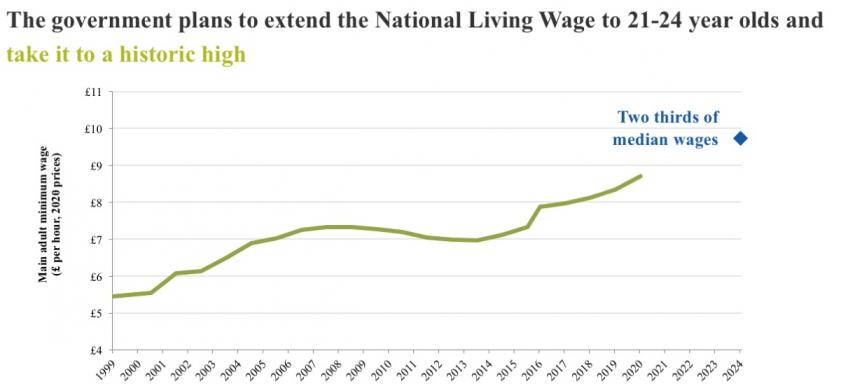

The Chancellor has raised the threshold for paying NICs on earnings, saving workers up to £85 a year, and announced plans to significantly raise the National Living Wage by the end of parliament. Both measures will boost the incomes of low earners. But if the aim is to tackle in-work poverty, they are not particularly well targeted. Only 8% of the gains from the NICs cut would accrue to the poorest fifth of working households. And only 22% of minimum wage workers live in the poorest fifth of all households.

The minimum wage is already at its highest ever level in real terms. The government has announced plans to extend it to younger workers and increase it to two thirds of median wages.

This would give the UK one of the highest minimum wages among developed countries.

A look ahead to the March 2020 Budget - event videos (26/02/2020)

Slides from the event

Background reading

Levelling up: what might it mean for public spending?

Much has been made of the Government’s promise to ‘level up’ across the UK.

9 March 2020

How should fiscal policy respond to the coronavirus (covid-19)?

It looks likely that responding to the coronavirus outbreak (covid-19) will be at the centre of Wednesday’s Budget. We look at some of the options the Chancellor has.

8 March 2020

Raise taxes, entrench austerity or break a fiscal rule: the choice facing the new Chancellor

26 February 2020

Government borrowing in 2019–20 set to be £55 billion higher than forecast four years ago - but £3.5 billion lower than the latest official forecast

If the pattern observed in the first ten months of the financial year continues for the next two, government borrowing will be £44 billion this year. This would be £3.5 billion lower than implied by the OBR’s restated March 2019 forecast. But it is worth recalling that just four years ago, in March 2016, a surplus of £10.4 billion was forecast for this financial year: i.e. we have seen a deterioration of around £55 billion in four years.

21 February 2020

Investing in those new Tory areas is top of Boris Johnson’s to‑do list

With a working majority it looks like we’ll have something approaching a full five-year parliament. Beyond “getting Brexit done” Boris Johnson, his chancellor Sajid Javid and the rest of the cabinet will have plenty on their plate to fill the time.

16 December 2019

UK Conservatives’ tax pledges could come back to bite them

Collection details

- Publisher

- IFS

More from IFS

Understand this issue

Should we worry about government debt?

11 April 2024

Public investment: what you need to know

25 April 2024

The £600 billion problem awaiting the next government

25 April 2024

Policy analysis

Recent trends in and the outlook for health-related benefits

19 April 2024

4.2 million working-age people now claiming health-related benefits, could rise by 30% by the end of the decade

19 April 2024

Oil and gas make Scotland’s underlying public finances particularly volatile and uncertain

27 March 2024

Academic research

Do work search requirements work? Evidence from a UK reform targeting single parents

1 February 2023

The impact of area level mental health interventions on outcomes for secondary school pupils: Evidence from the HeadStart programme in England

13 October 2022

Prioritization, risk selection, and illness severity in a mixed health care system

16 June 2022