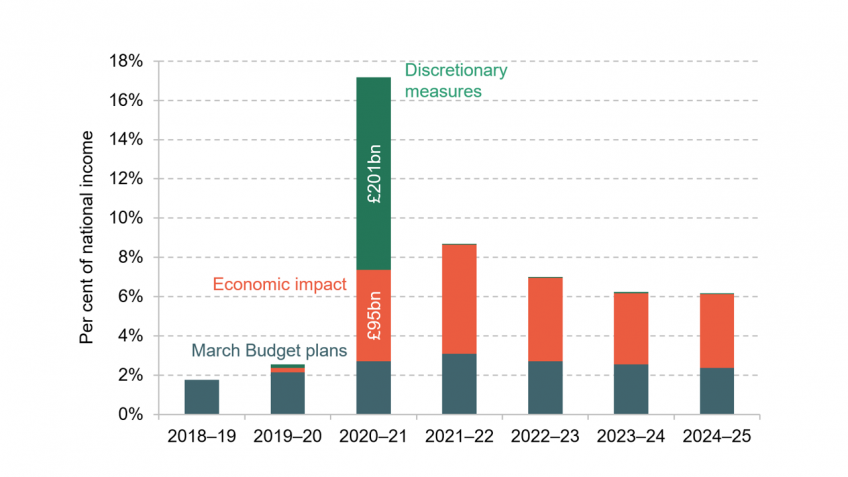

The COVID-19 pandemic and the public health measures implemented to contain it will lead to a huge spike in government borrowing this year. We forecast the deficit to climb to £350 billion (17% of GDP) in 2020–21, more than six times the level forecast just seven months ago at the March Budget. Around two-thirds of this increase comes from the large packages of tax cuts and spending increases that the government has introduced in response to the pandemic. But underlying economic weakness will add close to £100 billion to the deficit this year – 1.7 times the total forecast for the deficit as of March.

This year’s deficit will reach a level never before seen in the UK, outside of the two world wars of the 20th century. But what matters much more for the long-run health of the public finances is how complete the economic recovery will be. With the cost of borrowing at a record low, additional spending now that helps to deliver a more complete recovery would almost certainly be worth doing. For now, the government should focus on designing and delivering such support. But, in the medium term, getting the public finances back on track will require decisive action from policymakers. The Chancellor should champion a general recognition that, once the economy has been restored to health, a fiscal tightening will follow.

Drivers of the increase in borrowing in the central scenario

Source: Figure 4.5 in Chapter 4.

Key findings

1. Government borrowing this year is projected to climb to £350 billion which, at 17% of GDP, is a level never before seen in the UK, outside of the two World Wars of the 20th This compares with a March Budget forecast of £55 billion.

2. What matters most for the long-run health of the public finances is how complete the economic recovery will be. Under our central scenario, and assuming none of the temporary giveaways in 2020–21 are continued, borrowing in 2024–25 is forecast to be over £150 billion as a result of lower tax revenues and higher spending through the welfare system.

3. There will be significant pressures to increase public spending above March plans rather than eliminating all COVID-related extra spending. If a quarter of the additional public service spending announced in response to COVID-19 were made permanent, this would add £20 billion (in today’s prices) to spending by 2023–24. Depending on the size of any tax rise implemented by that point, this could add up to 1% of national income to forecast borrowing in 2023–24.

4. Prior to the pandemic, public sector net debt was around 80% of national income. This was considerably above the 35% of national income seen in the years prior to the financial crisis. In 2024–25, we forecast public sector net debt to be just over 110% of national income in our central scenario, close to 100% of national income in our optimistic scenario and close to 130% in our pessimistic scenario. Most of this is related to lower economic activity, rather than the large increases in spending implemented this year.

5. Once the economy has recovered, policy action will be needed to prevent debt from continuing to rise as a share of national income. Even if the government were comfortable with stabilising debt at 100% of national income – its highest level since 1960 – it would still need a fiscal tightening worth 2.1% of national income, or £43 billion in today’s terms. A rise in interest rates orfuture adverse economic shocks would make the task of preventing debt from rising further even more challenging.

6. The Conservative Party manifesto commitment to reduce debt as a share of national income over this parliament will be broken, and the current fiscal targets lie in tatters. But the high degree of uncertainty means that now is not the time to be announcing new targets, or the size, timing or nature of any fiscal tightening. Even the Autumn Budget of 2021 may be too soon for this. But Mr Sunak should champion a general recognition that, once the economy has been restored to health, a fiscal tightening will follow.