The COVID-19 crisis has pushed up government borrowing substantially, meaning that the Debt Management Office will need to sell a much larger value of gilts than normal. In our central scenario, we forecast the total amount to exceed £1.5 trillion, more than double the Budget forecast in March. While there is tremendous uncertainty around this figure, the total value will easily be the highest in recent history outside of the two world wars.

As a result, the UK’s public finances will be extremely sensitive to the effective interest rates on this debt, and to the risk that they rise. One way to address this risk is by selling more long-term, index-linked gilts while the effective interest on them is extraordinarily – some would say unsustainably – low.

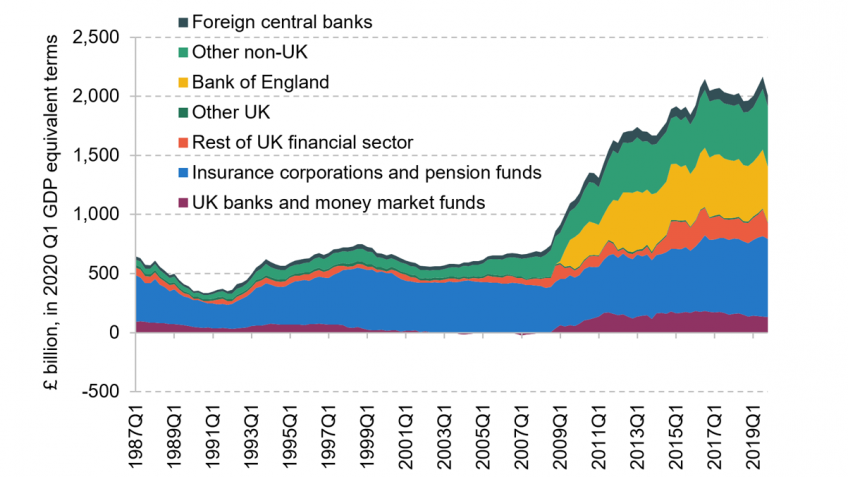

The expansion of the Bank of England programme of quantitative easing means that virtually all of this new debt has been bought by the Bank. The cost of financing this debt is the Bank Rate. While this remains historically low, it helps to hold down the government’s debt interest bill; however, debt interest spending will rise suddenly and sharply when the Bank Rate increases. Since government spending is now more closely tied to the Bank Rate, it will be even more important to ensure that the Bank of England continues to be – and be perceived as – independent and focused on its monetary policy mandate.

Holders of UK gilts (£ billion)

Note: Negative values represent repo positions.

Source: Figure 5.3 in Chapter 5.

Key findings

1. The Debt Management Office will need to sell a much larger value of gilts than normal. Our central scenario is for over £1.5 trillion to be raised through gilt issuance over the next five years, double the £760 billion forecast in the March 2020 Budget. There is considerable uncertainty around this amount. The enormous value of debt being issued means the costs of financing it just slightly wrong will be large.

2. Short- and long-maturity gilt yields have fallen even further from the already low rates seen prior to the pandemic. Yields are now much closer to the very low rates that have become typical for Japan.

3. The expansion of the Bank of England’s programme of quantitative easing means it has bought almost all of the extra debt issued during the pandemic. The financing cost of quantitative easing is Bank Rate, which is at record low levels, and has therefore further depressed government debt interest spending. However, the tilt towards Bank of England held debt means that the government’s debt interest bill will rise sharply if Bank Rate rises. It will be particularly important to maintain the credible independence of the Monetary Policy Committee in setting monetary policy, since the government has a more direct stake in Bank Rate.

4. Rising yields accompanied by stronger growth would be welcome. The risk to the public finances is that yields rise but growth prospects do not. One way to address this risk is by selling more long gilts. Long-term rates are extraordinarily – some would say unsustainably – low. Even 50-year gilts have been consistently offering just 0.5% a year (in nominal terms) since April 2020. With inflation anywhere near its 2% target, investors would see a negative return in real terms.

5. Contrary to the direction of recent policy, there could be considerable benefits from tilting the UK’s debt portfolio more towards index-linked gilts. This would have the advantage of locking in the current very low real rates for a greater share of government debt.

6. The Chancellor needs to signal that he takes the long-run health of the public finances seriously, that he fully respects the Monetary Policy Committee’s independence, and that he will not water down the inflation target in an attempt to help manage the public finances. Issuing a larger share of gilts on a long-term, indexed basis could only help to signal that intent.