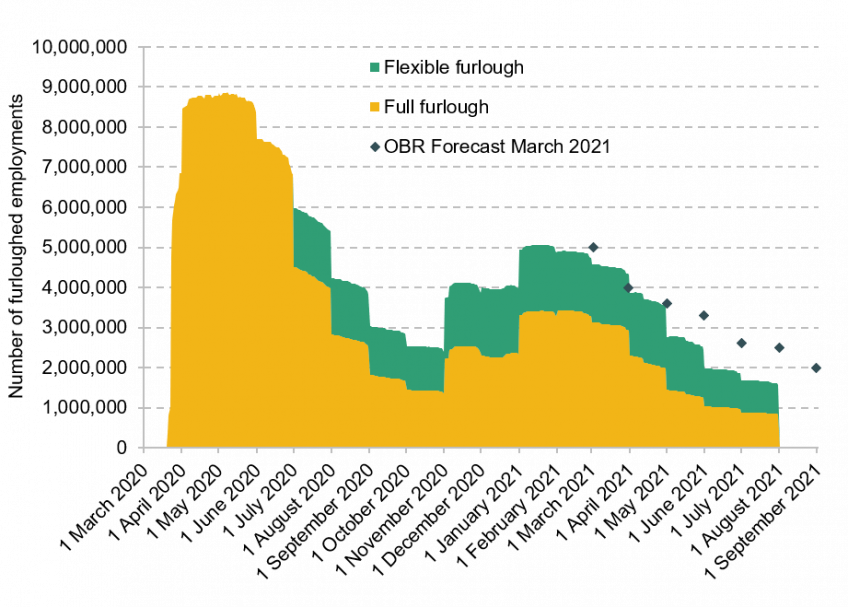

The government’s furlough scheme ended on 30 September. In many ways it has been very successful, albeit at a cost of almost £70 billion so far. While unemployment has risen and employment fallen since the start of the pandemic, the changes are nowhere near as dramatic as the falls in national income. As the furlough scheme comes to an end, a number of labour market challenges remain. We examine these challenges in detail and draw out key lessons for policymakers.

First, in late July, there were still 1.6 million people on furlough, of whom 900,000 were fully furloughed. At least some of these people will lose their jobs following the ending of the scheme. We examine in detail the types of people potentially at risk, including the region, age group and industry they belong to.

Second, despite the furlough scheme, around 1 million people were made redundant in the 15 months from April 2020 to June 2021. We look at who was most likely to be made redundant, and how difficult it has been for these people to find new work compared with those who lost their jobs before the pandemic.

Third, there has been a lot of interest in the situation facing younger adults, particularly those who left full-time education during the pandemic. We examine how hard it has been for them to find jobs, and the types of jobs that they have found.

Finally, the most high-profile trend during the summer has been the large increases in the number of unfilled vacancies. We examine in detail where, and in what industries, vacancies have risen particularly fast, and the potential reasons for these trends.

Number of employments furloughed, March 2020 to July 2021

Note: OBR forecasts from the March 2021 Economic and Fiscal Outlook are plotted for the last day of each month.

Source: HMRC furlough data, March 2020 to July 2021.

Key findings

- The furlough scheme is ending at the end of September. At a gross cost of almost £70 billion since March 2020, it has meant that rises in unemployment and falls in headline employment have been considerably smaller than during the recession between 2008 and 2011, when there was a far larger fall in GDP. Despite this success, significant challenges remain in the labour market. These include additional job losses when the furlough scheme ends, low re-employment rates for those made redundant, and high levels of vacancies in some sectors.

- The latest figures from HMRC show 1.6 million people were still furloughed in late July 2021, and 900,000 of these were fully furloughed. The highest furlough rates remain in industries severely affected by social distancing rules, such as accommodation & food and arts & entertainment. Rates in these sectors should come down following the easing of COVID-related restrictions.

- However, around 1.1 million people furloughed in July were in industries less affected by the easing of restrictions. For example, 110,000 employees remained furloughed in construction and 160,000 remained furloughed in manufacturing. These people are particularly at risk of job losses as the scheme winds down. Concerningly, around half live in households without another working adult, and a third neither have a degree nor live with another working adult. These people are susceptible to persistently low living standards should they be made unemployed.

- Despite the furlough scheme, around 200,000 people were made redundant per quarter between April 2020 and June 2021 (1 million in total), compared with only 110,000 per quarter in the year before the pandemic. We find that 56% of them found new employment within six months of redundancy, down from 66% prior to the pandemic. However, for Londoners, those aged 50+ and those without degrees, the chances of re-employment were much lower, with six-month re-employment rates at 44%, 35% and 49% respectively. This is concerning, since these groups are also disproportionately likely to still be furloughed. This compounds concerns about these groups being particularly at risk of long-term unemployment.

- Trends affecting workers aged 60+ are especially worrying: among those made redundant during the pandemic, 58% were not in, or searching for, work six months later, compared with just 38% among those made redundant in the three years prior to the pandemic. There is a risk that older workers made unemployed after furlough may drop out of the labour force altogether.

- While the fall in the re-employment rate for redundant workers compared with pre-pandemic is worrying, it is worth noting that the re-employment situation is not as bad as it was between 2007 and 2010, when only 51% of redundant workers found re-employment within six months. Given the degree of economic disruption during the pandemic, rates of re-employment have remained remarkably high – even before the most recent relaxation of restrictions in July.

- Concerns about unemployment are tempered by a record number of vacancies, which reached 1,034,000 between June and August 2021. There are a number of factors driving this, including: the furlough scheme discouraging job moves across firms; certain jobs becoming less attractive during the pandemic; and reductions in numbers of workers from the European Union. However, there is mismatch between the regions and industries with high vacancy rates and those with high rates of current or potential unemployment. This implies some need for ‘labour reallocation’, particularly towards the transport and retail sectors, and potentially across regions too.

- London appears hard-hit on multiple fronts. Despite comprising 14% of all employees, Londoners comprised 19% of those furloughed in July 2021 and 16% of redundancies during the pandemic. Among those made redundant, just 44% of Londoners had found new work six months later, compared with 58% for those living in the rest of the UK. Finally, while the number of UK-wide vacancies in September 2021 was 24% higher than in September 2019, the equivalent figure for London was just 8%.

- Young people who left full-time education during the pandemic initially struggled to find work. Among those who left full-time education in Summer 2020, only 63% were in work 3–6 months later – down from 75% in 2019. However, 9–12 months after leaving education, their employment rates had risen substantially, falling back into line with those of pre-pandemic cohorts. Given this recovery, coupled with the extensive pipeline of Kickstart jobs for young people, government resources and attention might be better focused on supporting other groups, such as older workers and those living in London.

This analysis was funded by the Nuffield Foundation as an early output of the 2021 IFS Green Budget.

The Nuffield Foundation is an independent charitable trust with a mission to advance educational opportunity and social well-being. It funds research that informs social policy, primarily in Education, Welfare and Justice. It also provides opportunities for young people to develop skills and confidence in science and research. The Foundation is the founder and co-funder of the Nuffield Council on Bioethics, the Nuffield Family Justice Observatory and the Ada Lovelace Institute. www.nuffieldfoundation.org | @NuffieldFound