Since the 2016 vote to leave the European Union, Brexit has become the policy area that dominates debate in the UK. It defined Theresa May’s government and will undoubtedly consume much of the government’s time and energy over the next few years, regardless of how the Brexit agenda evolves or who is in power.

Even so, in his first few weeks in office, Prime Minister Boris Johnson has set out an ambitious domestic policy agenda – including ‘fix[ing] the crisis in social care once and for all’; increasing funding for schools, the police, prisons and the NHS; and reinvigorating growth across the country. Likewise, the main opposition Labour party – which could take power if, as seems likely, an election is held later this year – used its last election manifesto and recent party conference to set out a wide range of domestic policy priorities. If either were to deliver on these promises, it would mark a notable change from the past three years when domestic policy has languished. But achieving such objectives will require the government to overcome several major barriers.

One of the issues will be finding the money needed to pay for some of these commitments. But progress on domestic policy under the last government was also hampered by the pressures of delivering Brexit, which consumed civil servants’, ministers’ and parliamentary time; the lack of a parliamentary majority and the breakdown of Cabinet discipline, which (even beyond Brexit) made it difficult to pass anything other than routine or relatively uncontroversial legislation; and unusually frequent turnover of ministers, which deprived several areas of domestic policy of the political focus, continuity and drive needed to push through changes.

In this chapter, we analyse these barriers to progress in Mrs May’s government and the extent to which they will continue to affect policymaking in different areas in the years to come. We also make recommendations to help the government – whoever is in power – to overcome some of these challenges.

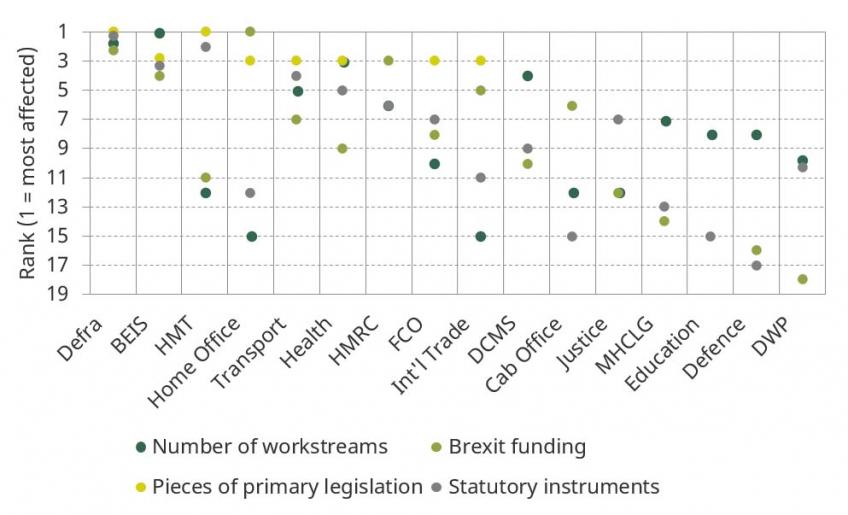

Departmental rankings on different measures of Brexit affectedness

Note: rankings are vertically offset (‘jittered’) to ensure all points are visible.

Key findings

- The all-encompassing nature of Brexit, the lack of a parliamentary majority and tight public finances created difficulties for Theresa May in advancing domestic policies. Brexit imposed significant demands on civil servants’ and ministers’ time, at the expense of progress on the government’s domestic priorities such as tackling ‘burning injustices’, reforming social care and delivering major infrastructure projects.

- Progress on domestic policies under Mrs May’s government was also undermined by poor Cabinet and party discipline and rapid turnover of ministers, both of which were partly a result of disagreement over Brexit. Mrs May’s task was made harder by her loss of the Conservatives’ parliamentary majority at the 2017 election, following which the government suffered defeats in parliament on both Brexit and non-Brexit legislation.

- A general election could break the current parliamentary deadlock, which has left new prime minister Boris Johnson hamstrung. But any future prime minister could still face many of the same difficulties in making progress on domestic policy. Brexit in whatever form will continue to place demands on civil servants’ and ministers’ time and could continue to test Cabinet discipline and party allegiances in parliament; keeping no deal on the table will make it harder still to make progress on domestic policy. Tight parliamentary arithmetic has made passing major legislation difficult. Without a general election – and perhaps with one – any government will struggle to build coalitions to pass new legislation.

- Negotiating a future trade relationship with the EU once the UK has left the bloc – with or without a deal – would be more difficult than negotiating the Withdrawal Agreement over the past three years. Negotiations with ‘third countries’ take place on a different legal basis with a more complicated process and require ratification by all 27 member states, while the difficult trade-offs revealed in the withdrawal negotiations’ would be likely to persist.

- Despite these challenges, the government could do more to make progress on domestic policy. It must set clear and limited priorities, enforce Cabinet discipline, avoid frequent ministerial reshuffles and set clear fiscal objectives. To increase its likelihood of success, particularly in controversial policy areas, the next government should be clearer about how additional public spending can help achieve its objectives and where other approaches (beyond just money) are needed, build cross-party support in some areas and make space for long-term thinking.