As the fourth Children’s Minister in the last 12 months, David Johnston is taking office in a crucial role at a crucial time. In this comment, we look at some of the big challenges that Mr Johnston will face when he starts work this afternoon.

Creating the newest branch of the welfare state

In the March 2023 Budget, Chancellor Jeremy Hunt announced a major expansion of the ‘free entitlement’ to a funded childcare place. This currently serves around 1.3 million children, with entitlements for all 3- and 4-year-olds and roughly a quarter of the most disadvantaged 2-year-olds.

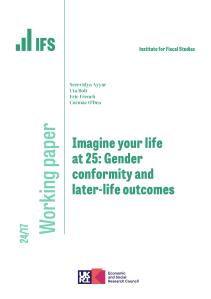

These reforms are another huge step in the creation of childcare as the newest branch of the welfare state. Spending has quadrupled over the last two decades, and these new entitlements will see spending double again over the next three years.

Figure 1. Core funding for the free entitlement

Note: IFS forecast based on a real-terms freeze in per-hour DSG funding rates and forecast demand based on ONS population estimates. Post-Budget spending excludes Barnett consequentials and assumes uplift for existing hours remains flat in real terms over the forecast horizon.

Source: Actual spending from Early Years Block of Dedicated Schools Grant, various years. From IFS Spring Budget analysis.

Delivering a funding system that works

But such a big reform is not without risk. When the new entitlements are fully implemented in September 2025, we estimate that Whitehall will directly control the price of around 80% of pre-school childcare in England (up from just under 50% now).

Having such a big weight in the market magnifies the risks of getting funding rates wrong. Providers will have much less scope to ‘cross-subsidise’ under-funding of free entitlement hours by charging higher fees for parent-paid hours, so setting the funding rate too low could see the market unravel.

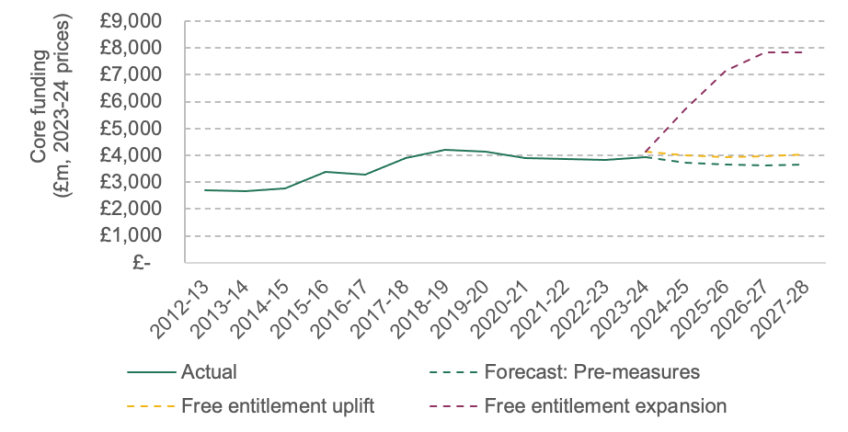

The government does seem to be aware of these risks, at least for the youngest children. The funding rate for 2-year-olds is set to rise by 30% (in cash terms) next year, and we calculate that the Budget settlements could see the average rate for under-2s reach about £11 an hour by 2027–28. This is significantly above existing market prices in most of the country.

Figure 2. Future free entitlement funding rates compared to market prices

Note: Current market rates are averages (means) from the 2022 Survey of Childcare and Early Years Providers, inflated to 2027–28 prices using the OBR’s March 2023 CPI forecast. ‘Proposed funding rates’ are indicative numbers only, based on IFS calculations taking into account the 2023 Budget plans and changes in population.

The offer for 3- and 4-year-olds, though, seems less generous. And it will come against a backdrop of sustained pressure: accounting for the specific costs facing childcare providers, core hourly funding for the 3- and 4-year-old entitlements is around 13% lower than its peak in 2017–18.

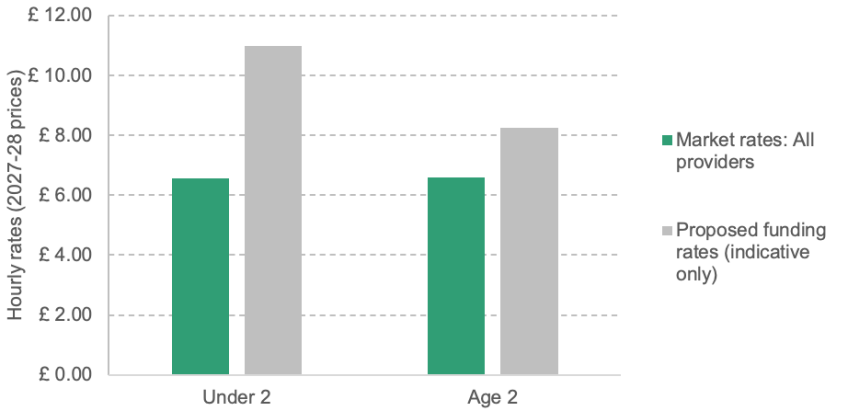

More broadly, the importance of getting the funding rate right also points to the importance of getting the process for funding the entitlement right. Traditionally, as Figure 3 shows, funding has followed a ratchet pattern: it is raised at one Spending Review and then held frozen in cash terms, as inflation quietly eats away at providers’ resources. Then, a few years later, the squeeze becomes apparent and rates are raised again.

Figure 3. Real-terms spending per hour on the 3- and 4-year-old entitlement (index: 2009–10 = 100)

Source: IFS education spending microsite – ‘Early Years’.

One major challenge for the new Minister will be overseeing the process for setting, reviewing and adjusting the funding rates for a sector that will increasingly rely on getting these right.

Defining the purpose of the early years system

The huge injection of resources for the early years sector – at a time when many other public services are being squeezed – speaks to the importance of what the early years system delivers.

The childcare system is also a vital support for working parents. On average, out-of-pocket childcare spending is 18 times higher for 1-year-olds using formal childcare than for 3- and 4-year-olds. The Budget reforms should help drive down these costs, at least for eligible families.

But early years education can also support children’s development, helping them to be ready for school and reducing the inequalities that arise early in life. In 2021–22 (latest available data), 5-year-olds who were eligible for free school meals were 20 percentage points less likely to have a good level of development than their peers.

The Budget reforms to the free entitlement move the system decisively towards the former goal and away from the latter. Offering funded childcare only to children whose parents are working targets support to the families who face the highest childcare costs.

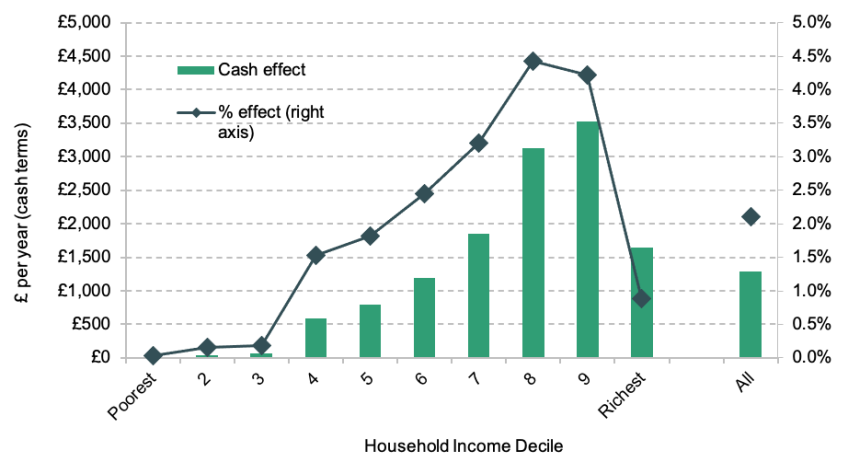

But it also, by definition, excludes children living in the poorest families. Based on current household incomes and childcare use, the poorest third of families will see very little benefit from these reforms. Of course, some of these families might be encouraged to take on (more) paid work in response to the new childcare offers, and so will move up the income distribution.

Figure 4. Distributional impact of free entitlement expansions (before behavioural changes)

Note: Sample is households with a child aged 9–35 months. % effect is as a share of pre-policy net household income.

Source: Calculations using TAXBEN, based on the Family Resources Survey 2017–19. From IFS Spring Budget analysis.

But, to the extent that the care on offer supports children’s development, this new system will not benefit the children who remain at the very bottom of the income distribution. It will therefore widen the already-large educational inequalities we see at the very start of children’s school careers.