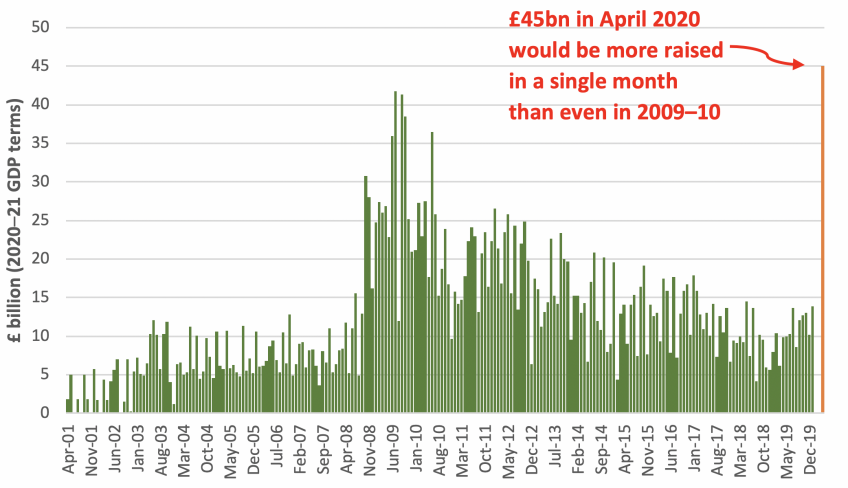

The Debt Management Office yesterday announced that from next Monday it would be conducting additional gilt auctions in order to raise a total of £45 billion this month. This is more than previously planned as greater sums are needed to finance the Government’s interventions in response to the Covid-19 pandemic. £45 billion in a single month is a lot. For example, as shown in Figure 1 below, it would be more than three times the largest amount raised in a single month in 2019 (July 2019, £13 billion) and slightly more than was raised at the peak of the financial crisis (July 2009, £28 billion which relative to the size of the economy is equivalent to about £42 billion today).

Figure 1. Monthly gilt sales

Notes: Cash figures uprated to 2020–21 terms using growth in nominal GDP. Source does not contain data for February or March 2020.

Source: Debt Management Office, monthly gross and net issuance report, (https://www.dmo.gov.uk/media/16278/website-monthly-gross-and-net-issuance-d4f-2019-20-end-dec-19-and-jan-2020.xls); authors’ calculations.

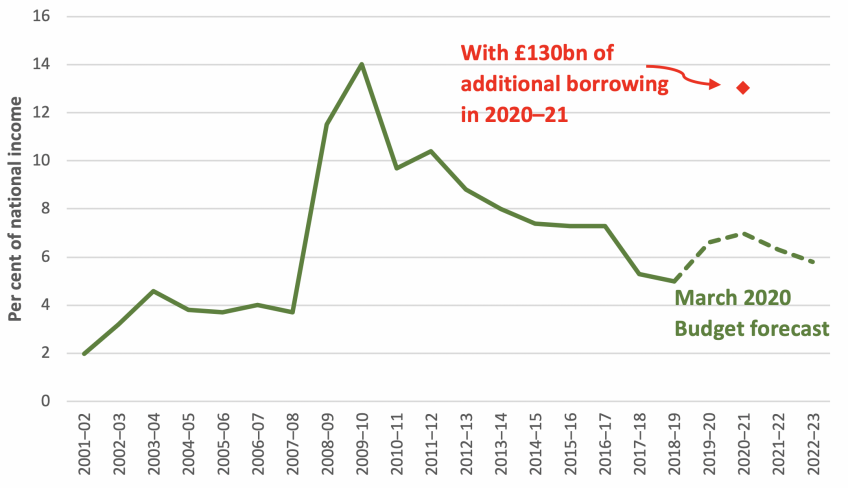

Even prior to the main response to the Covid-19 crisis in the UK, the Government was already planning to raise substantial sums from the markets. This is because it chose to finance increases in day-to-day spending and investment spending announced in the 2019 Spending Round and the 2020 Budget with increased borrowing rather than higher taxes. The Budget forecast implied that the “gross financing requirement” – the amount that the Government needs to raise to roll over existing debts and to finance new borrowing – was set to be £163 billion in 2020–21, and an average of almost £150 billion a year over the subsequent four financial years. As shown in Figure 2 below, as a share of national income, this would be quite substantially higher than the amount raised in the last two years and more than 50% higher as a share of national income than that raised immediately prior to the global financial crisis.

Figure 2. Gross financing requirement, by financial year

Source: Chart 3.15 of Office for Budget Responsibility, Economic and Fiscal Outlook, March 2020 (https://obr.uk/efo/economic-and-fiscal-outlook-march-2020/).

The current reduction in economic activity will increase government borrowing as revenues are depressed and spending pushed up. Appropriately, the Government has announced a set of policies aimed at supporting public services, household incomes and employers through this very challenging time. The cost of these interventions will also add to borrowing. In a piece last Thursday we set out how the combination of these two effects – reduced economic activity and the direct cost of the fiscal responses – could easily add £120 billion to borrowing over the next twelve months. A substantial package for the self-employed – announced last Friday – could add a further £10 billion to this figure. Overall this would bring total borrowing up to almost £190 billion, compared to the forecast produced just three weeks ago in the Budget of £55 billion. This would add almost 6% of national income to the amount needed to be raised which, as shown in the Figure, would bring it up towards the share of national income seen in 2009–10.

It is worth noting that this does not require the private sector to own substantially more gilts at the end of 2020–21 than was expected at the time of the Budget. Since then the Monetary Policy Committee of the Bank of England has announced that its programme of quantitative easing (QE) will be expanded by £200 billion. With the majority of this being used to purchase gilts this increase could easily be greater than even the substantial increase in the outlook for the deficit seen since the Budget (of, perhaps, £130 billion).

Low interest rates mean that the Government will be able to increase borrowing very cheaply. But this does not mean that it is costless. The larger amount of government debt held by the Asset Purchase Facility (APF) of the Bank of England will make the public finances much more exposed to changes in short-term interest rates (as this is the rate at which this borrowing is effectively financed). Recent years have seen interest rates continue to fall, and with them the amount spent on debt interest. For example in December 2014 the OBR forecast that central government debt interest spending (net of the APF) would be £60.1 billion in 2019–20, whereas its March 2020 Budget forecast was for this to be over £20 billion lower at just £38.2 billion. But what goes down can also go up. Were interest rates to rise sharply then, unless this went alongside improved growth prospects, greater debt would soon prove to be much more burdensome than it is at the moment.

Carl Emmerson, Deputy Director of the Institute for Fiscal Studies, said “The sharp decline in economic activity that is occurring at the moment, and the fiscal measures announced in response, will push up borrowing over the next year. As a result from next Monday the Debt Management Office will be raising more through gilt auctions. The Government is right to set out a substantial package of support for public services, households and employers. But more borrowing, effectively borrowed at short-term interest rates, will leave the public finances much more exposed to interest rate changes. Were they to rise significantly without a commensurate increase in our growth prospects then greater debt would soon prove to be much more burdensome than it is at the moment.”