The government has today announced an ‘Energy Price Guarantee’, holding the cost of energy for a household with typical consumption at an annual level of £2,500 over the two years from October. It has also announced that prices of gas and electricity will be capped for businesses, charities and the public sector for the next 6 months from October, with support for specific sectors beyond next March to be announced in the coming three months.

IFS Director Paul Johnson said ‘This is a huge policy intervention which could easily cost over £100 billion in the next year alone, with more to come in the following year. Given the scale of the package, the failure to provide any official sense of a costing was extraordinary, and deeply disappointing.

The scale of support will mean that each extra £1 households spend on energy is likely to cost the taxpayer 75p over the next year. This is clearly not sustainable in the long-term.

The government has bought us, and itself, some breathing space. It needs to be immediately working out its exit strategy from this huge and costly intervention. It is concerning that it appears to be committing to this policy through next year as well as this. It is perhaps forgivable not to be able to come up with something better designed and better targeted right now. Surely there should now be a concerted effort to come up with something better for next winter. Failure to do so would be enormously costly.’

- The new ‘Energy Price Guarantee’ will hold energy prices down so that the bill for a household with typical consumption is capped at £2,500 a year for the next two years. Alongside this is a six month cap on gas and electricity prices faced by businesses, charities and the public sector, with a promise of more support to follow.

- The cost of the package is highly uncertain, but is likely to be more than £100 billion over the next year alone. This would be more than the almost £100 billion spent in total on the Coronavirus Job Retention Scheme for furloughed employees and associated support for the self-employed over 18 months during the pandemic.

- While households will face energy prices that are about double what they were last winter, they will be little more than half of what they would have been without the guarantee. This means that every extra £1 a household spends on energy will be matched with around 75p from the taxpayer.

- We estimate that a household with typical energy consumption can expect to save £1,800 over the next 12 months as a result of today’s announcement; it would be £1,049 if the £3,549 price cap previously announced for October would otherwise have been unchanged for a year, but gas prices are expected to rise further and remain high throughout next year.

- European gas prices are high because of supply shortages, and some firms, households or governments will need to use less gas. If other European countries also attempt to subsidise household or business use of energy, the result could be a bidding war that raises the cost of providing support in all countries. It also risks a situation where there is simply not enough energy to go round which would require rationing or increase the risk of blackouts.

- While benefiting those who need to use more energy, the policy is not well targeted at those on low incomes who will struggle most to cope with higher costs. Half of the giveaway will go to the top half of the income distribution. The current crisis might necessitate such a response for the coming winter. But it is disappointing that the Government is not trying to implement a better targeted approach in the winter of 2023-24. With markets expecting energy prices still to be elevated in the following winter it is crucial that policymakers work now to ensure that better targeted approaches are available should they be needed beyond September 2024. The current approach is not sustainable in the long term.

How big is this intervention?

Based on energy consumption in 2019, holding energy prices for households at this level would cost around £60 billion over the next 12 months, with support for other energy users likely to take the cost above £100 billion over that period and additional cost in the following year. The eventual cost will depend on what happens to wholesale energy prices: higher-than-expected prices would push the cost up, lower-than-expected prices would reduce it. If wholesale prices remain elevated beyond the next two years it will also raise the possibility of the scheme being extended, adding to its cost.

This is a huge intervention. For comparison, over 18 months the Coronavirus Job Retention Scheme for furloughed employees had a gross cost of £70 billion, with the support for the self-employed over this period totalling a further £28 billion. Both of these schemes were extended for much longer than was initially envisaged and while the initial roughness in their design was understandable given the swiftness with which they had to be implemented, it was disappointing that subsequent extensions of these schemes were not better designed. The lesson from this is that there is clear risk that support for energy bills will need to run for longer than currently expected and it is crucial that policymakers work now to have better designed options available in future.

The £400 per household energy support payments and £150 council tax rebates announced earlier this year, and the additional supplements for those receiving certain benefits (such as universal credit, certain disability benefits and the winter fuel payment for pensioners), are being maintained alongside the new policy. These are worth a total of £25 billion to households. This means that the support being provided will be more generous than the government had expected when it announced its May support package: at that time, energy bills (before rebates) for a typical household were expected to reach an annualised cost of around £2,800 in October, £300 more than the £2,500 cost they are now being held down to.

How are the gains distributed?

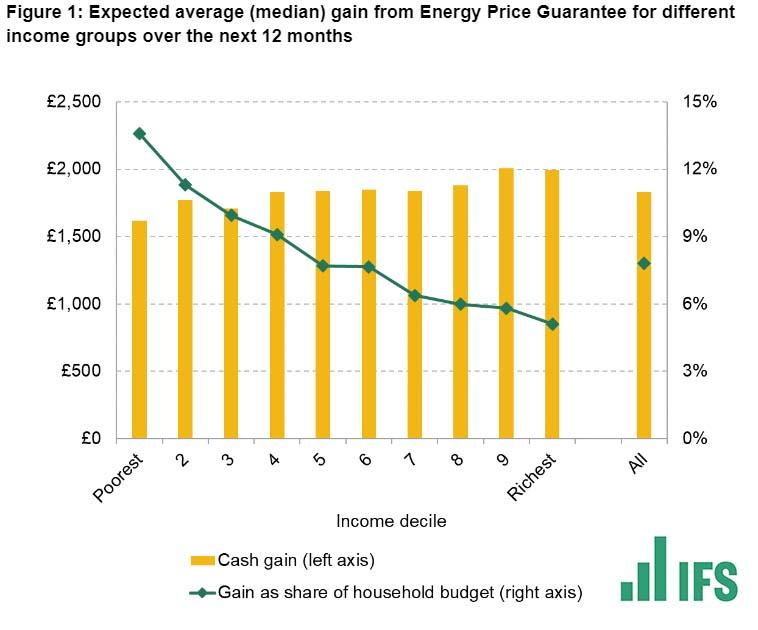

Artificially reducing prices for all households in this way is a blunt way of providing support, since while it gives more to households who need to use more energy, it also gives help to all households regardless of their resources. Figure 1 shows how average (median) gains for households vary across the income distribution. We estimate that a household with typical energy consumption can expect to save £1,800 (8% of its total spending) over the next 12 months as a result of today’s announcement; it would be £1,049 if the £3,549 price cap previously announced for October would otherwise have been unchanged for a year, but gas prices are expected to rise further and remain high throughout next year (with the predicted price cap without the price guarantee averaging well over £4,300 over the next 12 months).

Because households in different income groups use similar amounts of energy on average, the cash gain from the policy does not vary much among income groups. Among households in the lowest-income tenth of the population the average gain is expected to be about £1,600 over the coming year compared to nearly £2,000 for those in the highest-income tenth of the population. Just over half of the £60 billion giveaway to households will go to the top half of the income distribution.

But while poorer households will gain slightly less than richer households in cash terms, energy spending accounts for a much larger fraction of the budgets of the poorest. The Energy Price Guarantee will save a household with typical energy use in the lowest-income tenth an amount equivalent to 14% of their household spending, compared to 5% for the highest income tenth.

It is also important to remember that some low-income households use relatively little energy while others use much more: among the lowest-income tenth of households, one-in-four will face a bill of less than £1,250 per year under Energy Price Guarantee while another one-in-four will face a bill more than £3,500 per year. This is part of the reason why targeting the households who are most in need of support is difficult. Many poorer households will struggle with even the capped price this winter. Even accounting for the Guarantee, energy bills over the coming year will be around twice as high as they were in 2021.

Note: Authors’ calculations using spending data from the Living Costs and Food Survey 2019, aggregate electricity and gas consumption taken from the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy’s UK Energy Trends publication, economy-wide spending on electricity and gas from the Office for National Statistics’ Consumer Trends publication and energy forecasts from Cornwall Insights. The figures represent cash gains for the households with median energy usage within each group. Gains as shares of household budgets are fractions of median spending. Households are divided into income deciles based on net household income adjusted for household size and composition using the modified OECD equivalence scale.

Risks

As well as not being targeted on those most in need, the Energy Price Guarantee subsidises the price of energy for households. Each additional £1 households spend on energy will be matched by around 75p in additional spending by the taxpayer. Households will face much higher prices than last winter (and therefore have a greater incentive to reduce energy use than then) but will face much lower prices than they would have done had the cap not been in place. Unless additional steps are taken to reduce household energy use in the coming months, households will consume energy as if the price is 60% of its true economic cost. Business, charities and the public sector will also face distorted incentives for the period the Guarantee applies to them.

This highlights a fundamental issue. Prices are high because Europe faces severe gas shortages in the coming months. To correct the (large) mismatch between supply and demand, some users of energy - whether households, businesses or governments - will have to reduce their energy use. The less UK households reduce their energy demand, the greater demands placed on others. If other European countries also attempt to subsidise household or business use of energy, the result could be a bidding war that raises the cost of providing support in all countries. It also risks a situation where there is simply not enough energy to go round, which would require rationing or increase the risk of blackouts.

This mismatch between supply and demand is set to continue well into next year. The most recent forecast from the energy consultancy Cornwall Insights suggests that - in the absence of the freeze energy bills - typical bills would be expected to remain well above £4,000 for the typical household over the course of 2023. This compares to an annual price cap of £1,280 in October 2021. The price of forward purchases of natural gas (as captured by traded futures) also remains significantly elevated over the medium term. Purchases of gas for delivery in the winter of 2024-25, while trading at around half the current price of gas, remain around six times more expensive than the pre-crisis period. This points to a significant risk that the current policy - or a replacement - will need to be extended over a longer time horizon than currently planned, entailing even greater costs.

We must avoid this situation. A long-term energy price freeze is not sustainable. The government must act now to put systems in place to ensure that future support, if needed, will be better targeted to those in greatest need, and that households who are able face appropriate incentives to cut down their energy use. Time is in short supply too.