Today, the Oxford Review of Economic Policy publishes a special issue on Labour's economic record when in government between 1997 and 2010. As part of this, IFS researchers assess Labour’s record on income inequality and poverty. Here, we show how income inequality changed little but child and pensioner poverty fell significantly. We suggest, though, that these falls in poverty might prove fragile given that they were mostly based on very large increases in spending on benefits and tax credits. We also reflect on the main lessons for today’s policymakers. One such lesson is that how you spend money is more important than how much you spend. Governments need effective means to establish what works and what doesn't, and patience to see whether policies bear fruit in the long-run.

Labour had very clear objectives to reduce poverty amongst families with children and pensioners, and accorded these objectives high priority. Tony Blair made a famous commitment to end child poverty within a generation, and Gordon Brown promised to ‘to end pensioner poverty in our country”. However, it is much less clear that Labour took a strong view on the appropriate level of inequality within the top half of the income distribution, as indicated for example by Peter Mandelson’s famous statement that he was “intensely relaxed about people getting filthy rich as long as they pay their taxes.'

What happened to poverty and inequality under Labour?

If our summary of Labour's distributional objectives is accurate, then outcomes reflected those objectives quite closely. Turning first to poverty, both absolute and relative measures of income poverty fell markedly among children and pensioners - although the scale of the changes did not always match the considerable ambition, as set out explicitly in the case of the government’s child poverty targets.

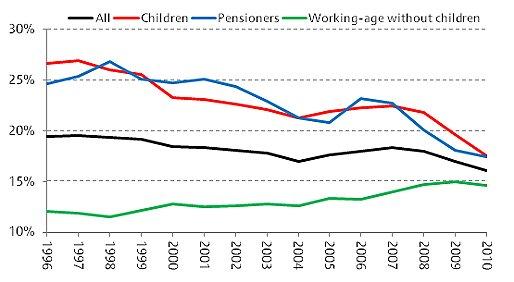

By contrast, the incomes of poorer working-age adults without dependent children - the major demographic group not emphasised by Labour as a priority - changed very little over the period. As a result they fell behind the rest of the population and relative poverty levels rose. Since childless working-age people started the period with low levels of poverty compared with other demographic groups, one consequence of these trends was that the risks of poverty across the major demographic groups converged under Labour. This is illustrated in the Figure below.

Figure: Relative poverty rates since 1996-97

Notes: Years refer to financial years. Poverty line is 60% of median income. Incomes measured before deducting housing costs.

Source: Family Resources Survey.

With falls in income poverty, one might expect to have seen a fall in income inequality. Indeed inequality did fall across much of the distribution. Those on relatively low incomes did a little better than those with incomes just above the average. However, those right at the top saw their incomes increase very substantially with the result that, on most measures, overall inequality nudged up slightly.

What drove these changes?

The substantial falls in pensioner and child poverty were largely driven by very significant additional spending on benefits and tax credits. Reforms since 1997-98 resulted in an £18 billion annual increase in spending on benefits for families with children and an £11 billion annual increase on benefits for pensioners by 2010-11 (see here). Our modelling suggests that child and pensioner poverty would either have stayed the same or risen, rather than fall substantially, had there not been these big spending increases. Meanwhile, Labour’s tax and benefit changes had relatively little net impact on the top half of the income distribution, or on low-income adults without dependent children – the group whose poverty rate did not fall. However, there is evidence to suggest that these reforms prevented a larger rise in inequality than actually occurred under Labour.

There were also increases in employment which had a small but detectable effect on income poverty. For example, reductions in the proportion of children living in workless families acted to reduce relative child poverty by about 2 percentage points.

There were many other Labour initiatives that could be considered anti-poverty policies. These include the introduction of the National Minimum Wage, Sure Start, increased financial support for childcare, significant increases in education spending and an expansion of the number of young people going on to higher education. Any payoffs from most of these measures will be long run, rather than immediate. It is of course very difficult to predict precisely what effects they will ultimately have on overall levels of poverty and inequality - and we will never know for sure, as their effects will inevitably happen alongside many other factors which continue to affect the income distribution. The verdict on the effects of Labour’s period in power on poverty and inequality is necessarily incomplete.

Reflections for the future

The fiscal climate is now very different and welfare spending can be cut back just as quickly as it is increased. As most of the currently detectable effects of Labour policy on poverty rates came through benefit increases, Labour’s legacy may prove fragile. Its durability will thus depend crucially on whether wider policies on things like education and childcare do have long-run impacts.

We would draw a few key lessons.

First, a sensible strategy for achieving distributional objectives will probably involve a lot of patience. Tax and benefit policy has quick impacts, but most other plausible policy levers do not. Many policies that might achieve sustainable impacts are likely to bear fruit only over the medium to long term, and certainly beyond the timeframe of a normal electoral cycle.

Second, the uncertainty about the long run effects of Labour’s policies on the income distribution highlights a wider point, which governments of all complexions should take seriously: major changes to things like childcare and education policy should, wherever possible, be implemented in ways which allow their effects to be robustly evaluated. We know much less than we should about policy effectiveness because so much major policy is implemented without proper evaluation (see here).

Finally, there are large gains to be had from designing the tax and benefit system skilfully: a government’s chosen level of redistribution can be achieved in more and less efficient ways. Stronger work incentives should be focused on those who are more responsive to such incentives (such as lone parents and parents of school-age children, as argued in the IFS’ Mirrlees Review). Labour’s reforms made some moves in this direction (see here). Another important goal should be simplicity and transparency. The current government’s Universal Credit offers a major opportunity to further this goal by replacing a jumble of overlapping means tests with a single integrated one, although reforms such as that to Council Tax Benefit risk undermining some of its potential advantages.