This is the second of three blog posts we’re posting following the TaxDev Tax Expenditures Workshop held on 6–8 February 2023 in Kampala.

Introduction

Tax exemptions are perhaps the most obvious example of a tax expenditure. They mean that no tax is charged on an activity or transaction that is usually subject to taxation. Examples found in different countries include: the exemption of the salaries of military personnel from personal income taxes; customs duty exemptions for the imports of capital goods or certain key inputs for export-focused or strategically important industries; and temporary corporate income tax exemptions or ‘holidays’ for foreign investors. Such exemptions are usually granted to provide a benefit to the individuals or businesses targeted and can entail a substantial revenue cost to the government.

Many countries’ VAT systems also contain a raft of exemptions. Some of these exemptions are primarily for administrative reasons, such as exemptions for small businesses – for which the revenues raised may not be worth incurring the tax administration and compliance costs – and for financial services, where the tax base is less easy to calculate than for most other services. Many of the exemptions are primarily to support particular industries or groups of consumers though – including exemptions for food and medicine, designed to ease the burden of VAT on the poor (although such exemptions are often poorly targeted). These can be some of the biggest individual tax expenditures that countries have, given how much households spend on these basic goods.

However, the design of the VAT system and the way exemptions operate within it mean that it’s possible for VAT exemptions to raise revenue and increase prices for businesses and consumers. This happens when the exempt goods or services are mostly used in the middle (rather than forming the start or end) of production chains.

The design of the VAT system

To see this, let’s imagine a simplified production chain for bread. As illustrated in Figure 1, this consists of a farmer who grows the wheat, a miller who grinds the wheat into flour, a baker who uses the flour to bake bread, and the retailer who sells that bread to the public.

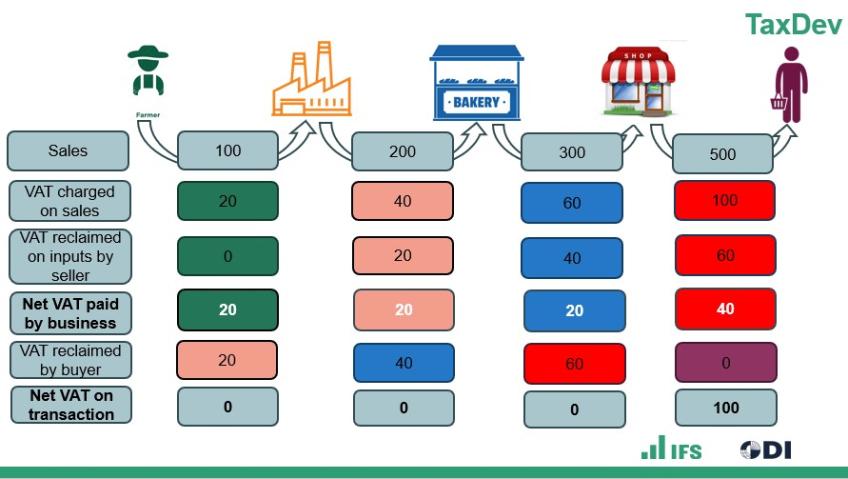

First, consider the situation where all goods are subject to VAT, which in our hypothetical country is charged at a rate of 20%. The farmer sells their wheat for a pre-VAT price of $100, and must charge $20 of VAT on top of this, which they then pay over to the revenue authorities. The miller sells the flour they produce for a pre-VAT price of $200. They must charge $40 of VAT on top of this, but they are able to reclaim the $20 of VAT they paid on the wheat they ground into flour, so they are liable to pay a net $20 in VAT to the tax authority. The baker sells the bread for a pre-VAT price of $300 and must charge $60 of VAT. After netting off the $40 of VAT paid on the flour they’ve used, they are again liable to pay a net $20 in VAT to the tax authority. Finally, the retailer sells the bread to consumers for a pre-VAT price of $500, with $100 of VAT due on top of this. After netting the VAT they paid when buying the bread from the bakery, they are liable to pay a net $40 to the tax authority. Adding up the net amount of VAT each business pays ($20, $20, $20 and $40) gives a figure of $100 in revenue collected on this chain of transactions.

If we break down how much VAT is paid by each business, it is based on the value added by that business: the difference between what they sell their good or service for, and how much they paid for the (non-labour) inputs they used in its production. The farmer, miller and baker are each liable for $20 in VAT: 20% of the $100 they generate in value-added. The retailer instead is liable for $40 in VAT: 20% of its $200 in value-added.

Figure 1: A simple supply chain illustration of the VAT system with no exemptions

But we can also break down how much VAT is paid by transaction. The farmer charges $20 of VAT on the sale of their wheat to the miller, but that is subsequently reclaimed by the miller. So no VAT is actually paid on that transaction. The same charging and reclaiming means no tax is actually paid on the sale of flour from the miller to the baker, or on the sale of bread from the baker to the retailer. It is only the final sale from the retailer to the public that is actually taxed by the VAT, because ordinary members of the public cannot reclaim the VAT they pay on what they buy, unlike registered businesses: the $100 in VAT charged by the retailer on this transaction is a final tax, equal to the total net VAT collected by the tax authority on this transaction chain. In this way, the VAT mimics a tax on sales to final consumers, except with the revenues being collected in chunks along the production chain.

How the effect of VAT exemptions varies according to where in the production chain it falls

Now let’s consider how VAT exemptions affect the amount of VAT collected. When a good or service is exempt from VAT, the business producing it does not have to charge VAT. But in addition, it cannot reclaim any of the VAT it paid on its inputs. The effect of exemptions on VAT revenues therefore depends on how much VAT is charged on goods and services before and after the one that has been exempted.

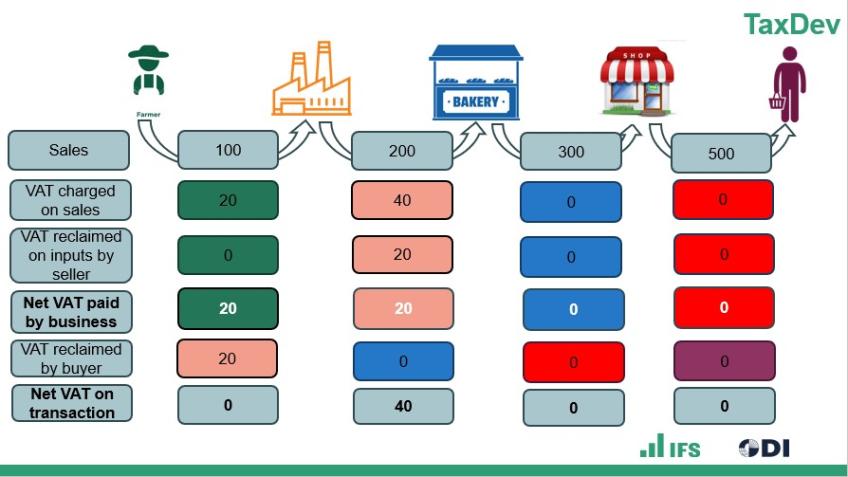

First, consider what happens if it was bread that was exempted from VAT, as illustrated in Figure 2. In this case, neither the baker nor the retailer is liable to charge VAT. But the baker cannot reclaim the $40 in VAT that they paid on the flour they used to bake the bread. This means that rather than $100 in tax being collected when everything was subject to VAT, $40 is collected when bread is made exempt from VAT.

Figure 2: A simple supply chain illustration of the VAT system with exemption for bread

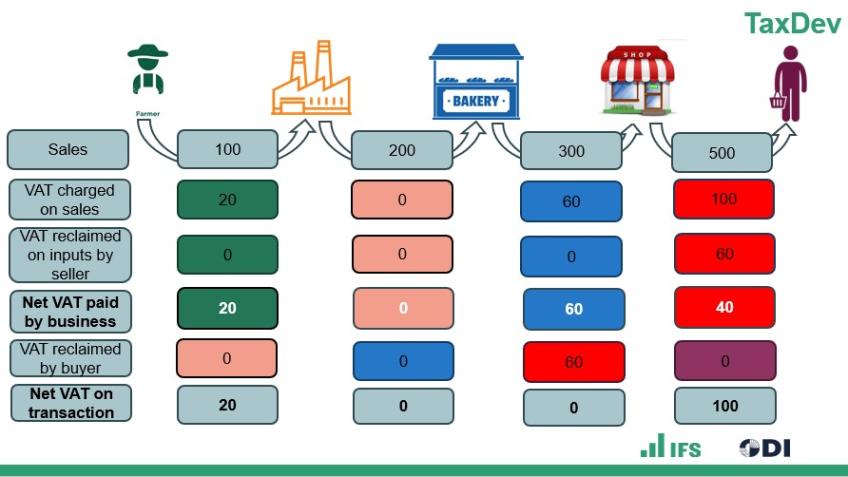

But what if it was flour that was made exempt instead, as illustrated in Figure 3? In that case, the miller would not have to charge VAT, but nor could they reclaim the $20 in VAT paid on the wheat they purchased from the farmer. However, that is not the end of the story. After buying the flour from the miller, the baker would still have to charge $60 of VAT on the bread they sell to the retailer but would not have any VAT to reclaim: the miller charged them no VAT, and the rules of the VAT system do not allow them to reclaim VAT paid earlier in the production chain. Finally, the retailer would have to charge $100 of VAT on the bread it sells to the public, and could reclaim the $60 in VAT it paid when purchasing the bread from the baker.

Figure 3: A simple supply chain illustration of the VAT system with exemption for flour

The upshot of this is that when flour is exempted from VAT, the total amount of tax due on this production chain is $120: $20 from the farmer, $60 from the baker and $40 from the retailer. This is $20 more than when there were no VAT exemptions.

Estimating the revenue effects of VAT exemptions

So here we have it, a tax exemption that raises revenues!

In reality, production chains are not as simple as the example we have used here. No sector is at the start of the chain: the farmer would require some inputs (such as fertiliser for the fields and petrol for the tractor) to grow wheat, and the suppliers of those inputs would in turn make use of other inputs. Few if any goods are used only in the middle or at the end of the chains: some flour may be used directly by the public to make their own bread, pastries and cakes; some bread will be used by cafes and catering businesses to make sandwiches that they sell to their customers.

However, some goods and services are more likely to be towards the start of production chains, some used as inputs by businesses in the production chains, and some used by consumers at the end of the chains. Tax exemptions on goods and services that are more likely to be used/purchased by businesses as opposed to by consumers are the ones that can potentially raise revenues. The likelihood and scale of positive revenue effects will be greater, the higher the share of business usage of a good or service, and the higher the amount of VATable inputs that are used in its production (which cannot be reclaimed when it is made exempt).

In order to estimate the revenue effects of VAT exemptions – for example, as part of tax expenditure reporting – one therefore needs information on the inputs used to produce different goods and services, and the use of these goods and services. This information is usually not available in tax administration records. Instead, one has to make use of so-called ‘supply and use tables’ produced as part of the process of putting together macroeconomic national accounts. These show the inputs used by and the outputs produced by (or supplied by) the different industries that make up the economy. This information can be used in conjunction with tax administration data to model the charging and reclaiming of VAT along production chains, in turn allowing the estimation of the revenue effects of VAT exemptions and other types of VAT expenditures (such as zero or reduced rates).

Concluding remarks

The amount of work to do this accurately can be significant, especially where the industrial sectors included in the supply and use tables do not closely match the VAT treatment of different goods and services, and/or where the tables are not regularly updated. The presence of informal businesses or small businesses not registered for VAT – and hence, like the sellers of exempt goods and services, unable to reclaim input VAT – also needs to be accounted for. VAT tax expenditure estimation is therefore one of the most challenging elements of tax expenditure reporting.

Corporate income tax expenditure estimation is also particularly challenging – not least because the design of the corporate income tax means that tax expenditures in one year can affect revenues (positively or negatively) in subsequent years. This will be the topic of our third and final blog post on tax expenditures.