The March 2015 Budget presented a set of figures for tax and spending over the next five years that, while technically reflecting government policy at the time, were inconsistent with the intentions that each of the coalition partners presented in their manifestos. In particular, neither party was committed to the profile for spending on public services, which OBR chief Robert Chote described at the time as a ‘rollercoaster’. It was, therefore, to be expected that the first Budget of the new parliament would contain significant measures in order to bring official forecasts closer to the Conservatives' manifesto commitments. But the Budget also contained policies not mentioned in the manifesto – in particular new tax rises and less deep cuts to spending over the next three years – that further affect the timing and composition of the remaining planned fiscal consolidation.

The March Budget set out a plan to achieve an overall budget surplus by 2018–19, through a nine-year fiscal consolidation package totalling 10.0% of national income (or £185 billion). At that time, the UK was just at the end of the fifth year of the planned consolidation, with four years remaining.

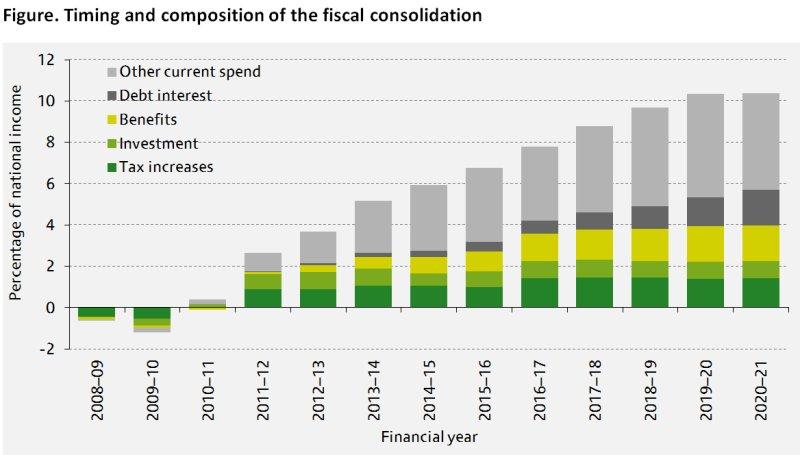

The new plan set out in last week’s Budget is for a slightly longer, slightly slower, but ultimately larger fiscal consolidation – lasting for 10 years and totalling 10.3% of national income (£194 billion) from when it first started in April 2010.

This means that the government is not now expected to achieve an overall budget surplus until 2019–20 (i.e. one year later than intended just four months ago in March). (The size, timing and composition of this consolidation plan have changed gradually over the last five years – this evolution is described in Chapter 1 of this year’s IFS Green Budget.)

The Budget also somewhat changed the composition of the consolidation – shifting more towards reliance on tax rises and cuts to social security spending, and away from reliance on cuts to public service spending.

The plan set out in March entailed 11% of the consolidation coming from each of net tax rises and social security cuts, whereas the new plan has 14% of the tightening coming from net tax rises and 17% from cuts to social security spending (as shown in the Figure below). With little change to investment spending plans this leaves the share of the consolidation coming from cuts to day-to-day spending on public services falling from 56% to 45%.

By the end of this financial year, two-thirds of the consolidation is set to have been done. Of the final third, 88% is set to come from spending cuts and 12% from tax increases. This is partly accounted for by the planned abolition of contracting out for defined benefit pension schemes and partly by last week’s announced net tax rise. However, while the former is expected to boost National Insurance contributions by £5 billion in 2016–17, more than £3 billion of this comes directly from public sector employers and so really reflects an additional pressure on public service spending.

The net effect of the slower pace of the consolidation and the greater reliance on tax rises and social security spending cuts is that the cuts required to public service spending over the next three years will be smaller than implied by the March Budget – and even somewhat smaller than implied by the Conservative party manifesto. However, most of this additional potential spending was committed by the Budget to the Ministry of Defence, meaning that the prospects for other unprotected departments are little improved.

Note: This Figure updates the numbers presented in Figure 1.6 of the 2015 IFS Green Budget to include the policy announcements made in the March 2015 and July 2015 Budgets. The Green Budget contains details of the methodology and sources used to construct this figure. The data underlying this figure can be downloaded here (xls).