Today’s figures from the ONS show that inflation in the year to September was just 0.5%. September is usually particularly important as the increase in prices over the year to that point is conventionally used in calculating how benefits and state pensions are to be uprated in the following April.

For the basic state pension and the new state pension current Government policy is triple lock indexation, which means that payments increase by the greater of growth in prices, earnings, or by 2½%. With the current economic turmoil leading to earnings falling by an estimated 1% over the year to July, and with today’s inflation figure of 0.5%, then this would lead to state pensions increasing by 2½% next April. A full basic state pension would rise from its current £134.25 per week to £137.60, while a full new state pension – which those who reached state pension age since April 2016 can receive – would rise from £175.20 per week to £179.60.

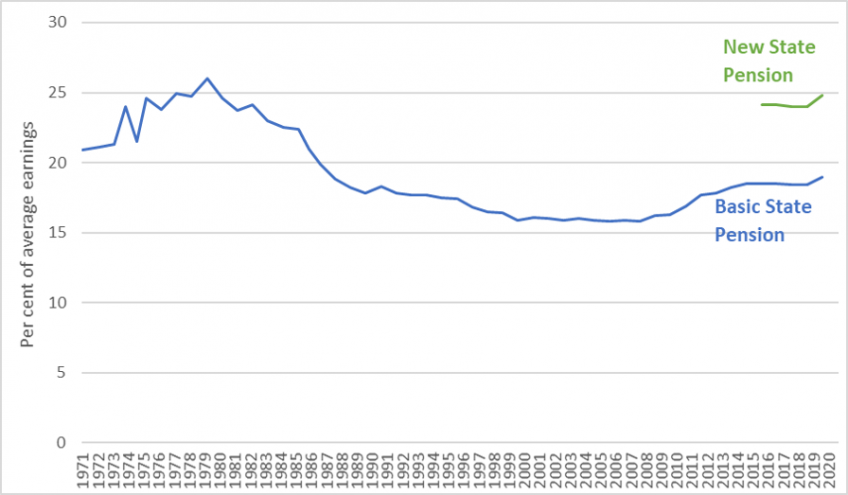

As shown in Figure 1 the basic state pension would rise from 18.4% of average earnings, which is already around the highest seen since April 1988, to 19.0% of average earnings which would be its highest share since April 1987. The new state pension would increase in value from 24.0% to 24.8% of average earnings. In real-terms both would rise further from their current record levels.

Figure 1. Value of a full basic state pension and full new state pension as a share of average earnings

Source: Updated from Department for Work and Pensions, Abstract of DWP benefit rate statistics 2019; using Office for National Statistics, Average weekly earnings in Great Britain: September 2020 and Office for National Statistics, Consumer price inflation, UK: September 2020.

Covid-19, and the triple-lock going forwards

In a goldilocks economy – not too hot, not too cold – one might expect inflation to be at target of 2% and for there to be sufficient productivity growth to result in nominal earnings growth of more than 2½%. In these years the triple lock would be no more (and no less) generous than earnings-indexation. However in periods of economic turmoil the triple lock is particularly generous to pensioners. This is because the value of the basic state pension and new state pension are protected when earnings growth is weak but, despite this, increase fully with any subsequent recovery in earnings. As a result the value of these payments would increase more quickly over time if the economy experiences periods of boom and bust rather than if the economy experiences consistent (but the same average) growth.

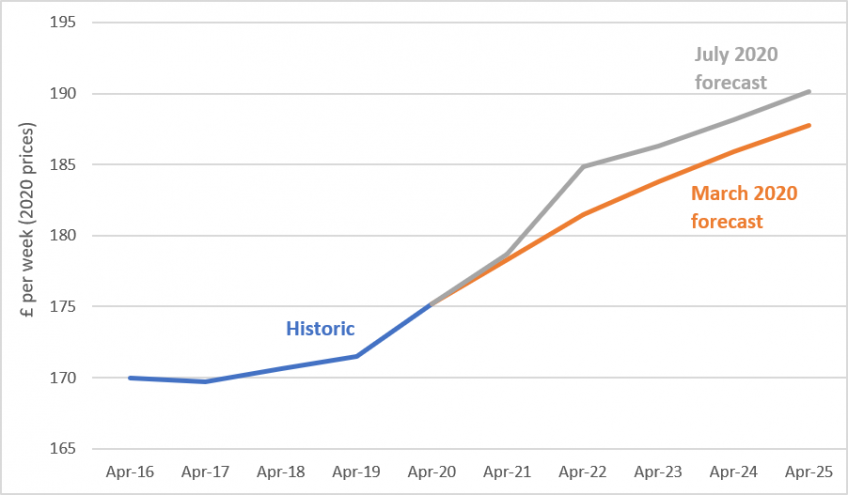

Earnings are forecast to bounce back reasonably strongly in the coming year as – hopefully – the severe and lengthy lockdown introduced in response to the pandemic does not need to be repeated. As a result the OBR forecast in July that over the year to July 2021 average earnings will grow by 5%. Under triple-lock indexation, the state pension would then increase in line with this bounce back in earnings in April 2022 and the boost to these payments in April 2021 relative to average earnings would be locked-in. The OBR estimates that in 2024–25 state pension spending will be £3.2 billion more than it would be were it indexed to earnings throughout this period. These state pensions would also be more generous in real terms than was forecast to be the case in March, as is shown for the new State Pension in Figure 2. This is despite the working age population now being expected to be poorer in 2024–25 than was expected in March.

Figure 2. The real value of a full new state pension under the triple lock, March 2020 and July 2020 forecasts compared

Source: Updated from Department for Work and Pensions, Abstract of DWP benefit rate statistics 2019; using Office for National Statistics, Average weekly earnings in Great Britain: September 2020 and Office for National Statistics, Consumer price inflation, UK: September 2020.

The record of the triple-lock to date

This is far from the first time this rachet effect has occurred. The last eleven years have seen terrible growth in average earnings. As a result, under the triple lock earnings-indexation has – remarkably – only applied three times, with more generous than earnings-indexation set to apply eight times. As shown in the Table below, by next April this will mean the basic state pension will have increased by 41% over the last eleven years, compared to 25% if it had been indexed in line with inflation (as measured by the CPI) or by 22% if it had been indexed in line with earnings. (A double lock, of indexation in line with the greater of earnings or prices, as was proposed in the Conservatives 2017 manifesto but subsequently dropped as part of their deal with the Democratic Unionist Party, would over the entire period have implied an increase of 34% over this period.)

Table 1. Triple lock indexation since April 2011

| Triple-lock | Index used | CPI | Average earnings |

April 2011 | 4.6% | RPI | 3.1% | 1.3% |

April 2012 | 5.2% | CPI | 5.2% | 2.8% |

April 2013 | 2.5% | 2.5% | 2.2% | 1.6% |

April 2014 | 2.7% | CPI | 2.7% | 1.2% |

April 2015 | 2.5% | 2.5% | 1.2% | 0.6% |

April 2016 | 2.9% | Earnings | –0.1% | 2.9% |

April 2017 | 2.5% | 2.5% | 1.0% | 2.4% |

April 2018 | 3.0% | CPI | 3.0% | 2.2% |

April 2019 | 2.6% | Earnings | 2.4% | 2.6% |

April 2020 | 3.9% | Earnings | 1.7% | 3.9% |

April 2021 | 2.5% | 2.5% | 0.5% | –1.0% |

Total | 41% |

| 25% | 22% |

Source: Updated from D. Thurley and R. McInnes, State Pension triple lock, June 2020, House of Commons Library; using Office for National Statistics, Average weekly earnings in Great Britain: September 2020 and Office for National Statistics, Consumer price inflation, UK: September 2020.

The House of Commons Library has estimated that the triple-lock in 2020–21 is costing £5.6 billion more than earnings-indexation since 2011–12 and £1.2 billion more than had state pension indexation been “double locked” over this period.

The triple lock has also cost much more than was originally expected – as it was (not unreasonably) expected that earnings would grow faster than 2½% and prices more often than has been the case. In the June 2010 Budget the triple lock was estimated to cost £450 million in 2014–15. However the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) estimated in 2015 that in the same year it actually cost £2.9 billion, i.e. over six times more than originally forecast.

So what’s the solution?

There are good reasons not to expose pensioner incomes to the downs of the economic cycle. But having done that it is less clear why they should still benefit from the ups of the subsequent economic recovery.

One solution that avoids the rachet effect was suggested by IFS researchers in our 2015 election analysis (page 15 here) and was subsequently recommended by the Work and Pensions Select Committee who describe it as a ‘smoothed earnings link’. Under this proposal next April would see state pension payments rise by today’s inflation figure of 0.5% (rather than by 2½%), with growth in their value relative to average earnings being subsequently clawed back by setting future increases in line with inflation until a full basic state pension and a full new state pension returned to their pre-Covid shares of average earnings, at which point earnings-indexation would resume.

Other temporary fixes are doubtless possible. But it is also important to remember that it is not just that the triple lock is badly designed for the current pandemic. Rather that at some point it was always going to prove unsustainable. The OBR has previously projected that in fifty years time triple lock indexation would add 1.0% of national income, or around £20 billion in today’s terms, to spending on state pensions relative to a policy of earnings-indexation. The current pandemic has highlighted this and, I suspect, brought forward the date at which the triple lock is abandoned.

We are thankful for funding from the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC), as part of UK Research and Innovation’s rapid response to COVID-19, grant number ES/V00381X/1.