Below we outline an initial response from IFS researchers on the Conservative party manifesto. We take policy areas by turn but this is not a full assessment.

Further analysis, including costings and a comparison with other manifestos, will be published next week.

Responding to the Conservative Party manifesto, IFS Director Paul Johnson said:

"If the Labour and Liberal Democrat manifestos were notable for the scale of their ambitions the Conservative one is not. If a single Budget had contained all these tax and spending proposals we would have been calling it modest. As a blueprint for five years in government the lack of significant policy action is remarkable.

"In part that is because the chancellor announced some big spending rises back in September. Other than for health and schools, though, that was a one-off increase. Taken at face value today’s manifesto suggests that for most services, in terms of day-to-day spending, that’s it. Health and school spending will continue to rise. Give or take pennies, other public services, and working age benefits, will see the cuts to their day-to-day budgets of the last decade baked in."

"One notable omission is any plan for social care. In his first speech as prime minister Boris Johnson promised to 'fix the crisis in social care once and for all'. After two decades of dither by both parties in government it seems we are no further forward."

"On the tax side the rise in the National Insurance threshold was well trailed. The ambition for it to get to £12,500 may remain, but only the initial rise to £9,500 has been costed and firmly promised. Most in paid work would benefit, but by less than £2 a week. Another £6 billion would need to be found to get to £12,500 by the end of the parliament. Given the pressures on the spending side that is not surprising."

"Perhaps the biggest, and least welcome, announcement is the 'triple tax lock': no increases in rates of income tax, NICs or VAT. That’s a constraint the chancellor may come to regret. It is also part of a fundamentally damaging narrative – that we can have the public services we want, with more money for health and pensions and schools – without paying for them. We can’t."

Corporation Tax

Boris Johnson has announced that a Conservative government would not go ahead with the planned reduction in the rate of corporation tax from 19% to 17% next April.

The government’s estimates imply that cuts to the headline rates of corporation tax from 2010 to 2019 cost £13 billion a year. The additional reduction from 19% to 17% that was due next April would have cost a further £6 billion – money that a Conservative government would now have available to spend on other things.

Corporation tax revenue has increased since 2010 even while the headline rate has been cut. But that does not mean that rate reductions have increased revenue.

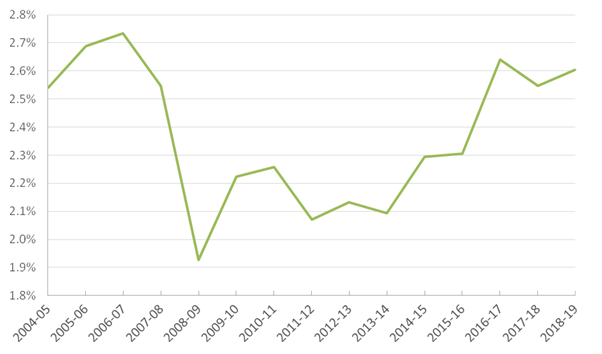

First, as Figure 1 suggests, much of the rise in revenue since 2010 is simply recovering from the effects of the financial crisis and recession. We would have expected a recovery in profits even if the corporation tax rate had not been cut.

Figure 1. Onshore corporation tax revenue as a share of national income

Source: OBR Public Finances Databank, accessed November 2019

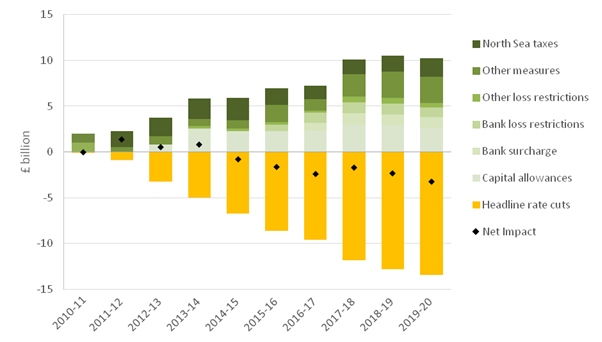

Second, while the government has reduced the headline rate of corporation tax, at the same time it has increased corporation tax in other ways, including reducing capital allowances for investment, introducing the bank surcharge, restricting companies’ ability to offset past losses against future profits, and a raft of anti-avoidance measures. As shown in Figure 2, taken together these measures recoup around £10 billion of the £13 billion spent reducing the headline rate: the net effect of reforms (shown by the diamonds in Figure 2) has therefore only been to cut corporation tax by about £3 billion a year.

Figure 2. Impact of reforms on corporation tax revenue, by year

Source: OBR Policy Measures Database, and IFS calculations using various HM Treasury Budget documents

Stuart Adam, a Senior Research Economist at the IFS, said:

"Corporation tax revenues today are at much the same the level they were at before the financial crisis, despite a 7 percentage point cut in the headline rate. That is largely because a series of other changes have increased the effective rate of corporation tax: the headline rate is not all that matters. Abandoning the proposed further 2 percentage point cut will leave the government with about £6bn a year more revenue than it would have received had it gone ahead with the cut."

The Triple tax lock: Commitment not to increase rates of income tax, National Insurance or VAT

The Conservative manifesto states “We promise not to raise the rates of income tax, National Insurance or VAT. This is a tax guarantee that will protect the incomes of hard-working families across the next Parliament.” Income tax, National Insurance contributions (NICs) and VAT are the three largest taxes, together accounting for almost two-thirds of total tax revenue.

If tax rises were deemed necessary in the next parliament, the Chancellor would still have scope to increase other taxes. And revenue from income tax, NICs and VAT can be increased without increasing rates, by applying them to a wider range of income/expenditure.

We estimate that the net impact of all tax measures announced since 2010 has been to increase revenues by around £20 billion a year. As well as an increase in the main rate of VAT from 17½% to 20%, a substantial boost to revenues has come from restricting income tax pension tax relief for those on high incomes, introducing the bank levy and abolishing contracting out into defined benefit pension arrangements.

Carl Emmerson, Deputy Director at the Institute for Fiscal Studies, said:

“The commitment not to increase the rates of income tax, VAT or National Insurance contributions is not good policymaking. Should a structural hole appear in the public finances, it might be deemed necessary to increase taxes. While there are plenty of other ways in which additional revenue could be raised, previous Conservative Chancellors have on occasion deemed increases in rates of NICs or VAT to be a reasonable way to raise large sums. This commitment would also make it harder to deal with the concern that the tax system – particularly National Insurance – under-taxes self-employment relative to employment, as Phillip Hammond found when he tried to address this issue."

Spending on public services

The Conservative government had already planned to increase day-to-day spending on public services by £11.7 billion next year with some further increases for schools and the NHS in subsequent years. Their manifesto adds just £2.9 billion to current plans in 2023–24. This is a very modest increase indeed – it would boost spending in that year by less than one-third of one per cent of what was already planned.

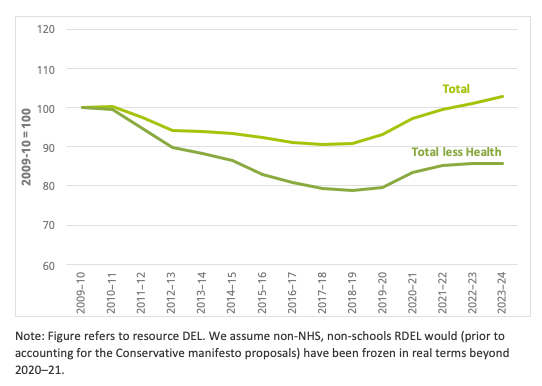

The manifesto pledges appear to leave little scope for spending increases beyond next year outside of those planned for health and schools. Even in 2023–24 day-to-day spending on public services outside of health would still be almost 15 per cent lower in real terms that it was at the start of the 2010s.

Figure 3. Day-to-day spending on public services, 2009–10=100

The Conservative Party manifesto proposes a larger boost to capital spending of £8.1 billion in 2023–24. This would be 15% higher than the £53.8 billion pencilled in at the time of the last Budget and, if delivered, would take public sector net investment to 2.4% of national income. This would be higher than what has been sustained at any point in the last 40 years.

However it would leave investment spending well below the Conservatives proposed ceiling of 3% of national income. And the boost to capital spending is much smaller than that proposed by either Labour (£55 billion a year) or the Liberal Democrats (£26 billon a year).

Carl Emmerson, Deputy Director at the Institute for Fiscal Studies, said:

“The increases in day-to-day spending proposed in the Conservative Party manifesto are very modest, adding less than £3 billion a year, or less than one-third of 1 per cent, to spending by 2023–24. Under these plans the boost to spending set out in the September Spending Round would, for many spending departments, prove to be short-lived. More significant increases in capital spending are planned – but even these are far smaller than what would be permissible within the Conservatives stated fiscal targets.”

Health spending

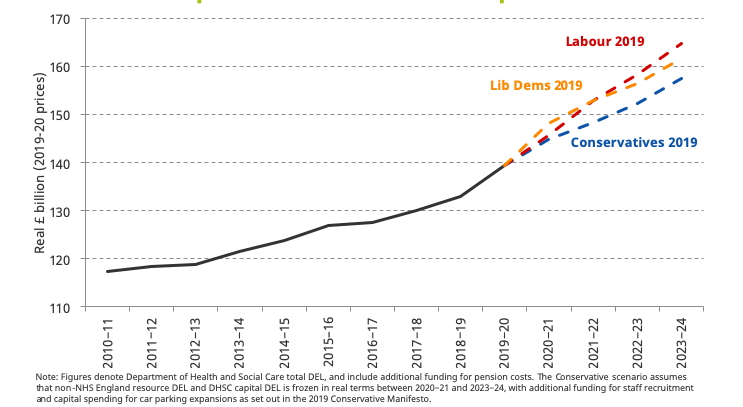

Today’s proposals from the Conservatives restated the commitment to provide additional funding for day-to-day spending on the NHS in England first announced by Theresa May in Summer 2018, with a small additional amount of money in order to help provide more GP appointments. These proposals would increase day-to-day spending on the NHS in England by an average of 3.3% per year between 2019–20 and 2023–24. Labour and the Liberal Democrats proposed average growth rates of 3.8% and 3.7% in their manifestos last week.

Importantly, health spending in England also includes other day-to-day health spending, covering activities such as staff training and public health initiatives, and capital spending. Both Labour and the Liberal Democrats have set out additional spending in these areas. The Conservative plans set out some additional funding for recruiting and training nurses in each of the next four years, and some capital spending for expanding hospital car parking facilities, but have failed to set out complete plans for wider health spending over the entire four year period. The promise to build 6 new hospitals over the next 5 years – and to begin planning for 34 more – was also reiterated today but no additional capital funding proposed to cover these costs.

Assuming that the rest of the health budget is frozen in real terms, today’s announcements imply that overall spending on the Department of Health and Social Care would increase by 3.1% per year between 2019–20 and 2023–24. This compares with the 4.3% growth rate implied by Labour’s spending plans, and the 3.8% growth rate under Liberal Democrat plans.

Figure 4. Health spending plans in Conservative, Labour and Liberal Democrat manifestos

School spending

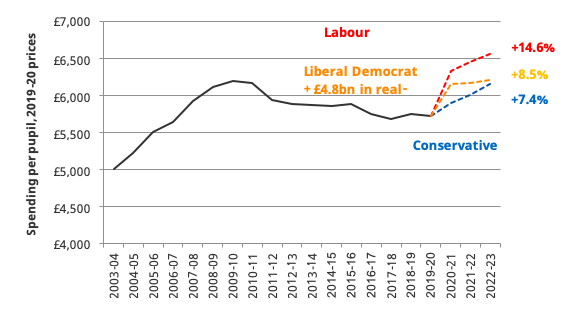

Today, the Conservative party confirmed plans from the 2019 Spending Round to increase school spending in England by £7.1 billion in cash-terms by 2022–23 as compared with today. This represents a £4.3 billion increase in real-terms, or a 7.4% real terms rise in spending per pupil. This would near enough reverse cuts since 2009–10. However, this would still leave spending per pupil no higher in 2022–23 than it was 13 years earlier.

By way of comparison, Labour have committed to a £7.5 billion real terms increase by 2022–23 or a 14.6% rise in spending per pupil. The Liberal Democrats have committed to a £4.8 billion real terms rise by 2022–23 or an 8.5% rise in spending per pupil, with plans for further increases in future years.

Luke Sibieta, Research Fellow at IFS, said:

“All the main parties now seem committed to delivering large increases in school spending over the next few years. The Liberal Democrats are committed to a slightly larger increase than Conservative plans, though both would effectively reverse cuts of 8% in spending per pupil over the last decade. Labour would go further still, with a 15% real-terms rise in spending per pupil over the next 3 years.”

Figure 5. Schools spending plans in Conservative, Labour and Lib Dem manifestos

Time-limited childcare spending targeted at school age children

- Unlike Labour and the Liberal Democrats the Conservative manifesto does not include any plans to offer a further extension of free, pre-school childcare. Instead, it promises £210 million a year for “at least” three years (plus another £210 million in capital funding in 2021) to encourage schools in England to develop or expand ‘wrap-around’ childcare (before and after the school day) and childcare outside of term time.

- Offering support to schools and other third-sector providers to increase wrap-around childcare provision would benefit parents of school-age children by giving them more childcare choices.

- While the Conservatives proposal would benefit some families with school-age children, the sums involved – an increase in day-to-day spending of £210 million a year – are modest both in comparison to current spending on the childcare system (£5.4 billion) and relative to the giveaways promised by Labour and the Liberal Democrats (which the parties cost at £4.3 billion and £9.9 billion in today’s prices, respectively).

- Most working parents are already eligible for support with wrap-around childcare costs, either through tax reliefs (on childcare vouchers or through a tax-free childcare account) or, for low-income parents, through the childcare subsidies in the benefits system. In 2017 – the last year for which data are available – we spent £1.8 billion on these subsidies in England. Currently, parents also have a ‘right to request’ that their child’s school considers providing wrap-around care.

Christine Farquharson, a Research Economist at IFS, said:

“Unlike Labour and the Liberal Democrats, the Conservatives have a relatively modest childcare offer which is focussed on older, school-age children. The Conservatives are also promising to focus spending on supporting childcare settings to increase childcare provision, rather than on offering parents support with childcare costs. This offer could benefit parents of school-age children by increasing their childcare options, but it’s less clear whether it will have a big effect on parents’ working patterns or children’s development.”

Cuts to National Insurance contributions (NICs)

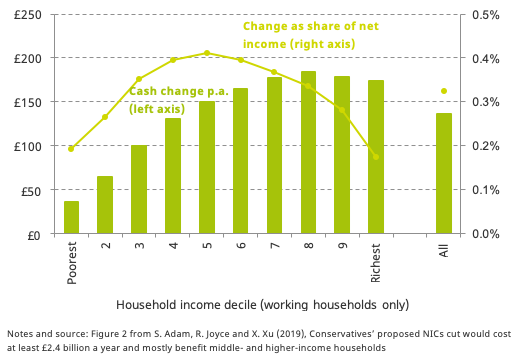

The Conservatives propose to raise the point at which employees and the self-employed pay NICs to £9,500 in 2020–21. This compares to the currently planned level of £8,788. The reform would cost a little over £2 billion a year and would mean that, at any point in time, around 430,000 fewer people would pay NICs, and those still paying it would be paying £85 per year less. (Liability would be £104 lower than this year, as highlighted in some of the Conservatives’ pronouncements, but £19 of that reduction would have happened anyway because of the normal uprating of the threshold with inflation.)

16 million households would gain by £120 a year on average, since many households have more than one earner.

Cutting NICs is about as well targeted as a direct tax cut can be on low earners. On the other hand the biggest average gains still go to the middle and upper-middle of the household income distribution. Only 8% of the giveaway goes to the lowest-income fifth of working households. That number would be 64% if the same money were allocated to increasing work allowances in universal credit – though that would come at the cost of bringing many more families into means-testing.

Figure 6. Distributional effects of raising employee and self-employed NICs thresholds to £9,500 among working households, by household income

The Conservatives have said that their “ultimate ambition” is to raise the NICs threshold to £12,500, and have said that this would save workers about £500 a year. Their manifesto costings do not include doing this by 2023–24: raising the threshold to £12,500 by then would cost around £8.6 billion a year in today's prices, whereas they have only budgeted £2.3 billion (in today’s prices) for the NICs cut that year, just enough to increase it to £9,500 in April 2020 and uprate it with inflation thereafter. Furthermore, even if the threshold were raised to £12,500 by 2023–24, NICs payers would save at most £389 a year – not £500 – since the NICs threshold is already due to rise with inflation (so only any above-inflation increase would be an additional giveaway: that is the basis on which the Conservatives themselves have costed their policies).

Xiaowei Xu, a Research Economist at IFS and an author of the research said:

“The NICs cut set out in the Conservative party manifesto is modest: it would benefit workers by at most £2 a week at the cost of just over £2 billion a year. The Conservatives have stated that their ‘ultimate ambition’ is to raise the NICs threshold to £12,500, which they say would save workers about £500 a year. Their manifesto costings do not allow for this by 2023–24. Even if the £12,500 were reached in 2024, by the end of the next parliament, this would only save workers a maximum of £364 a year – not £500 – since the NICs threshold is already due to rise with inflation.”

Minimum wage

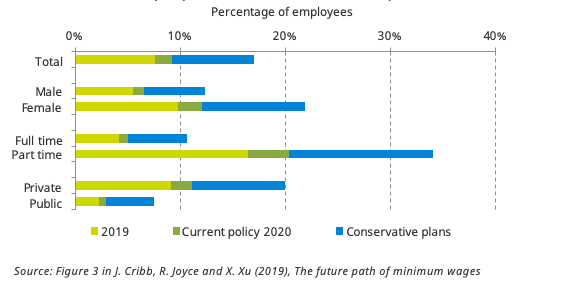

The Conservative party has pledged to extend the National Living Wage (NLW) to 21-24 year olds and raise it to two thirds of median wages by 2024. This is a smaller and more gradual rise than Labour's proposal to set a £10 minimum for all workers aged 16 and over in 2020. But it would still substantially expand the coverage of the minimum wage for those aged 21 and over:

- The number of employees directly affected by the minimum wage would double from 1.9 million to 4.3 million – around one in six employees – by 2024.

- A fifth of all private sector employees, and a third of part-time employees, would be covered by the Conservatives proposed minimum wage.

- The number of hospitality sector employees on the minimum wage would more than double from around 350,000 today to around 820,000 by 2024.

- The share of 21-24 year old employees directly affected by the minimum wage would rise from 9% today to 36% by 2024.

Figure 7. Percentage of employees aged 21+ directly affected by the minimum wage in 2019, under current policy for 2020 and under Conservative plans for 2024

The direct benefits from minimum wage increases would mostly go to middle-income households. Only 22% of minimum-wage workers today live in the poorest fifth of working households, partly because low-paid workers often live with higher earners. Many of those who do live in low-income households would see part of their gains clawed back through reduced entitlements to means-tested benefits such as universal credit.

Xiaowei Xu, a Research Economist at IFS said:

“Recent minimum wage rises have boosted earnings and there is little evidence that they have damaged employment, so there may well be scope for further increases. But the Conservatives’ plans would take us into uncharted waters in the UK and give us one of the highest minimum wages among developed countries. We need to tread carefully to ensure that, if the employment prospects of the low-paid do start to be impacted, policymakers can change course before it is too late.”