Introduction

This weekend, on Saturday 6th July, the state pension age rises again, to 65 years and 5 months. Naturally, this means that some will have to wait longer to receive their state pension. But it also means that some with low incomes must wait longer to receive Pension Credit – a means-tested benefit that aims to provide pensioners with a ‘minimum income’.

In fact, Pension Credit has recently been subject to an important change meaning that many couples will have to wait many years longer to first claim Pension Credit. Prior to 15th May 2019, an eligible couple could claim Pension Credit when the older member reached their state pension age, whereas now they have to wait until the youngest member has reached state pension age. This has been termed the ‘mixed-age couples’ reform because it affects couples where one partner is, and one is not, above state pension age. The Department for Work and Pensions estimates that affected couples will lose around £5,900 per year on average as a result of the reform. Based on current patterns of Pension Credit receipt, something like 115,000 couples might be affected by the policy, once it is fully rolled out, at any one time.

In this observation, we assess who is likely to be affected by this change, how long for, and how it changes the benefit system for older couples.

What is Pension Credit?

Couples who receive Pension Credit get a payment that tops their income up to at least £255.25 per week (they may also be entitled to other benefits such as housing benefit). Couples with some of their own income are eligible to receive an extra amount (called ‘savings credit’) of up to £15.35 per week. The government expects to spend £5 billion on Pension Credit this year, with 1.5 million claimants and therefore an average award of just over £60 per week.

Under the reform that came in on 15th May, low income couples where only one of them has reached the state pension age who would otherwise be eligible for Pension Credit must now wait until the younger of them reaches state pension age. This only affects couples who had not claimed Pension Credit or pensioner housing benefit before 15th May.

The older member of the couple can of course claim their state pension, with a full single-tier pension worth £168.60 per week. If the couple have little or no other income, they may be able to claim Universal Credit (UC). This typically means they will receive less as UC is less extensive than Pension Credit. In fact, if the older partner is entitled to a full new state pension and the couple own their own home, they typically would not be entitled to any UC. If they do receive UC (for example, because they rent their home), then unless the younger member of the couple has a health condition which is deemed to prevent work, or is looking after young children, or is a full-time carer, he or she will be expected to look for paid work.

Who will be affected by the new rules?

Since this reform reduces entitlements to benefits for low income families around state pension age, the reductions in income are clustered in the bottom 40% of the income distribution. This means couples with net household incomes under £25,000 per year. The median net income of affected couples is around £19,400. Once the policy is fully in place, about 250,000 households (or 3% of pensioner households[1]) will (at a point in time) have lower entitlement than if the reform was not in place, losing on average £4,500 per year. This would suggest a saving to the Government of just over £1 billion a year.

However, take-up of Pension Credit is quite low (60%[2]), and clearly those that do not claim Pension Credit (or pensioner housing benefit) do not lose out from the reform. DWP estimate that only 115,000 mixed age couples currently claim Pension Credit or pensioner housing benefit and so can lose from the reform. Their analysis suggests that losers will lose on average £5,900 per year – larger than the amount we estimate, which may be down to those with greater entitlements to Pension Credit (and therefore with more to lose) being more likely to take it up.[3] This suggests a saving to the Government of around £0.7 billion a year.[4] As well as having relatively low incomes, affected couples are disproportionately likely to live in social housing (35%), although majority are owner occupiers (53%). About half contain at least one person in receipt of a disability benefit.

How long are couples affected by the new rules?

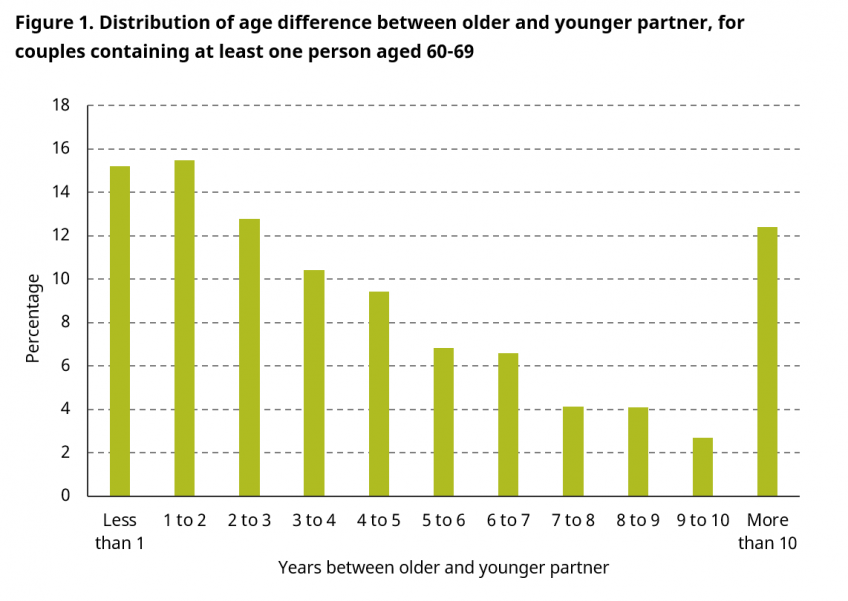

The length of time that low income families are affected by the new rules depends on the difference in age between each member of the couple: since almost no couples are comprised of people with exactly the same date of birth, virtually all are ‘mixed age’ couples at some point: the issue is for how long they can expect to have one member below and one above the state pension age. Figure 1 shows the average age difference of couples that contain someone aged 60 to 69. This gives an estimate of how much longer low income couples would have to wait to claim Pension Credit. 22% of households containing someone aged 60-69 are singles, and so are not affected by the reform. Of the 78% that are couples, the median age difference between the older and the younger partner is 3 years and 7 months. But some couples have considerably smaller age differences, and other have much higher, as is shown in Figure 1. Only 15% of those in couples are born within a year of their partner, and 30% have an age difference of less than 2 years. For 12% of couples, the age difference is more than 10 years, meaning that they will have to wait at least an additional decade to become potentially eligible for Pension Credit – at which point the older member will be above 75. These age differences look similar when looking at groups that are more likely to be eligible for Pension Credit, such as couples with low levels of education.

Source: Authors’ calculations using the Family Resources Survey, 2017–18.

Discussion

Couples which have large age gaps are instructive because they help us to understand the trade-offs the government faces when designing means-tested benefits around state pension age.

Under the old rules, a poor couple born exactly 10 years apart could start to claim Pension Credit when the older one reached state pension (66 next year). This means that the younger partner could have been receiving Pension Credit from age 56 (an age at which 83% of men and 72% of women were in paid work in 2018). Given that Pension Credit has no work-search conditions attached to it, if the younger partner is paid a relatively low wage, they have very weak incentives to work, and can receive financial support from the state without conditions from an age well below state pension age. Some people might see this as the state being overly generous towards a person who may well have the ability to support themselves and their partner through paid work. Arguably it is in some cases unfair for the state to provide Pension Credit to such a person when it only provides the less generous UC – with work search requirements – to a single person of the same age.

On the other hand, imagine the same couple eight years later. The older member of the couple is 74 and the younger is 64 (an age at which in 2018, only 38% of women and 50% of men were in paid work). Under the new rules such a couple would not be entitled to Pension Credit, and if the younger partner is not in work and they have no other income, they will likely have an income well below the ‘minimum income’ that Pension Credit seeks to provide to pensioners. Again, some people might see this as a couple falling through the net that Pension Credit is supposed to provide to poor pensioners: this 75 year old will be receiving less support from the state than a single person of the same age.

So, one way of seeing the trade-off is this: the government’s new rules mean that people well below state pension age can no longer live on Pension Credit, so their work incentives have been improved. However, that comes at the potential cost that those whose younger partner is unable or unwilling to work will face a less generous safety net potentially for many years after they have themselves reached the state pension age.

There are various intermediate alternatives between the old and new systems. One is to provide a level of support for low income mixed age couples that is more generous that UC but less so than Pension Credit. Another is to allow a couple to claim Pension Credit once the older partner has reached a certain age (say, five years above state pension age), even if the younger partner is still below state pension age. Or the average age of the couple could be used to determine eligibility, rather than the highest or lowest. However, any such options would – relative to the new system – likely imply higher benefit spending and weaker work incentives for some older people.

References:

[1] This is among all pensioner households – including those who are single, or where both members are above state pension age, who obviously do not lose from the reform.

[2]https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/income-related-benefits-estimates-of-take-up-financial-year-2016-to-2017.

[3]https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/mixed-age-couples-benefit-impacts-of-ending-access-to-pension-credit-and-pension-age-housing-benefit/mixed-age-couples-benefit-impacts-of-ending-access-to-pension-credit-and-pension-age-housing-benefit. £5,900 figure derived using the costing for 2023–24 and number of couples affected in that year, downrated to 2019–20 prices using the OBR forecast for CPI.

[4] Though, because the reform only affects new claims, it will take some time for this saving to be fully realised: in 2023–24 the government expect the reform to be saving them only £360 million per year (2019–20 prices).