This morning, the ONS published its monthly public finance release for April, giving us an initial snapshot of the public finances under lockdown. It throws the enormous impact of the restrictions on the public finances into sharp relief.

Commenting on the numbers Isabel Stockton, research economist at the IFS, said

“In April, the government borrowed more than in any previous month on record and more than forecast in the March Budget for the whole of 2020–21. The public health measures put in response to COVID-19, and the policy giveaways to help businesses and households through this challenging time, substantially depressed government receipts and pushed up government spending. Central government cash receipts in April 2020 were £25 billion lower than in April 2019. Over half of this decline was explained by VAT. Reduced consumer spending and the deferral scheme - enabling businesses to pay VAT later - meant that net receipts were below zero in April 2020, compared to £13 billion received in April 2019. Receipts of income tax, National Insurance Contributions and corporation tax were all also below their April 2019 level. Spending was pushed up by the Coronavirus Job Retention Scheme which in its current form is forecast to cost £14 billion a month.

There will clearly be a substantial spike in borrowing this year. What this means for policy will depend crucially on the shape and extent of the recovery that follows. If the increase in borrowing is a one-off then one option could be to manage down the elevated debt stock gradually over many years. Should higher borrowing endure – for example, because the economy doesn’t fully bounce back – then tax rises or spending cuts would be needed if borrowing is to be returned to its pre-crisis path. Any additional spending pressures arising from the current crisis would also put upward pressure on taxes.”

Public sector borrowing increased substantially

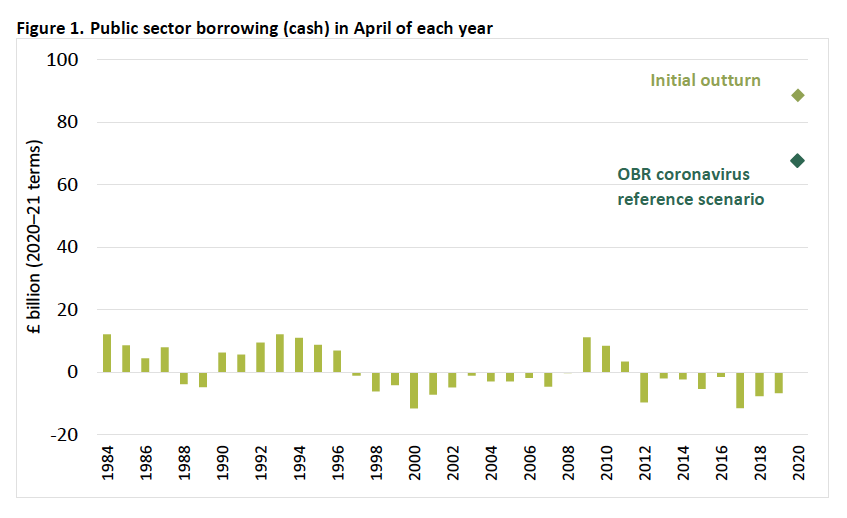

Figure 1 shows a measure of borrowing in cash terms, the difference between what the public sector spent and what it received in revenue. Borrowing is subject to seasonal fluctuations, so we compare this month’s data to the outturn in the month of April in previous years. As the OBR projected in its Coronavirus reference scenario, this month’s borrowing dwarfs anything seen in nearly forty years of data. In April 2020 borrowing (on this measure) was £89 billion, even larger than the £68 billion forecast in the OBR’s scenario. The comparable figure for April 2019 was a surplus of £7 billion, and the most recent peak in April 2009 when (in today’s terms) borrowing was £11 billion.

Just two months ago, at the March 2020 Budget, the government forecast borrowing (again on this measure) of £25 billion over the course of the whole financial year (with at the time this measure of borrowing being flattered by a forecast £43 billion of receipts from financial transactions by the Bank of England), whereas it has now borrowed more than three times that in a single month.

Note: Figure shows Public Sector Net Cash Requirement (PSNCR). Past borrowing figures uprated to 2020–21 in line with forecast growth in nominal GDP.

Revenues down and spending up

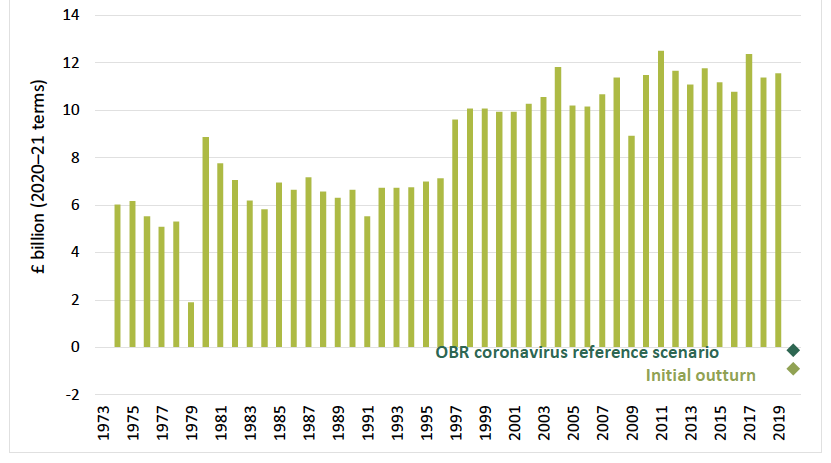

Underlying the sharp increase in borrowing are both a collapse in government revenues and a large increase in public spending. Figure 2 compares cash receipts of VAT (which in 2019–20 comprised one-fifth of total revenue) in April of each year going back to April 1973 when VAT was introduced in the UK. VAT revenue on a cash basis has collapsed. In April 2020 they were £12 billion below what they were in April 2019 – they were below zero because repayments made to businesses exceeded tax payments made to the government.

This sharp decline in revenue reflects both the economic slowdown and the VAT deferral scheme. Therefore – at least in large part – this represents a policy success: large parts of the economy have, as was intended, shut down to stop the spread of COVID-19, reducing VAT owed. In addition, firms have been able to defer payment on their VAT liabilities until the end of the financial year. To the extent that businesses had short-term liquidity problems, this measure will help support them through the crisis and revenue will come in later in the year. However, some fraction of businesses is likely to face not just a liquidity but a solvency issue and not survive, meaning that some VAT revenues will never be paid. The OBR assumes that 5% of the VAT that is deferred will never be repaid and, on this basis, forecast that the deferral cost will mean that ultimately revenues are depressed by £1.9 billion as a result.

Figure 2. Cash VAT receipts in April of each year

Note: Past revenues figures uprated to 2020–21 in line with forecast growth in nominal GDP.

Another, smaller revenue stream that nevertheless highlights the effects of the lockdown is receipts from fuel duties. These were 4.2% of receipts in 2019–20. Since there is no deferral scheme for fuel duties, the effect is unambiguously attributable to changes in spending patterns under lockdown. Figure 3 shows that revenues in April 2020 were just £1.2 billion, whereas in April 2019 they were £2.4 billion.

Figure 3. Receipts of fuel duties in April of each year

Note: Past revenues figures uprated to 2020–21 in line with forecast growth in nominal GDP. Accrued receipts shown, for this tax these generally coincide with cash receipts.

Under normal circumstances, accruals measures, which attempt to capture revenues and spending as they fall due, provide a more accurate picture of the public finances than cash measures. However, accruals measures rely on forecasts and are therefore slower to reflect changes in the economic environment. Borrowing in cash terms could under or overstate the true (or accrued) scale of borrowing during the coronavirus pandemic. On the one hand, companies are able to defer their tax liabilities, which means that cash payments from firms will understate accrued government revenues, which leads to cash measures of borrowing overstating accrued borrowing. But on the other hand it is possible for cash measures to understate borrowing.

An example of this on the spending side is with the Coronavirus Job Retention Scheme (CJRS). HMRC has indicated that the total value of claims in almost two months of operation up until May 17 is £11.1 billion, far less than the cost of £14 billion per month that the OBR has forecast in its reference scenario. But employers may still enter backdated claims while the scheme is open, which would eventually count towards spending in the month they accrued, even if the money has not yet been paid out. This would lead to cash spending understating accrued spending, and borrowing in cash terms understating borrowing in accrued terms.

Implications for fiscal policy

Today’s initial figures are merely the first snapshot of the effect the coronavirus outbreak will have on the public finances. Over the months to come, more and better data will help build a more complete picture. Based on today’s data, it is nevertheless clear that borrowing will increase to historic highs this year. Borrowing of around £300 billion, or 15% of GDP, as the OBR’s Coronavirus reference scenario projects, certainly seems plausible, a level which has not been reached since the Second World War (but, as a share of GDP, would still be below that borrowed in the four years from 1940–41 to 1943–44).

For subsequent policy, the size of the spike this year will be less relevant than the shape of the subsequent recovery. Just like successive UK governments paid off the debt arising from the Second World War over several decades, one approach to the one-off increase in borrowing associated with the pandemic would be to bring it back down over the course of many many years.

One cost of this approach is that it would increase our exposure to the risk of increases in interest rates that were not accompanied by greater growth. This would require careful management by Chancellor Rishi Sunak and also several of his successors. Also while a one-off, albeit substantial increase in borrowing might not necessarily require policy action, it is possible that higher borrowing will, to some extent, endure. This is for three reasons.

• First there will be additional debt interest spending to finance, though at current interest rates this impact is modest.

• Second, if – as is likely – the economy does not rebound fully from the current crisis then receipts will to some extent continue to be impaired.

• Third, it is possible that even after the immediate crisis has passed, voters and policymakers will push for increased public spending in some areas. This could be the NHS and social care, but also preparedness and stockpiling for future pandemics or other disasters, or a higher level of social insurance in “normal” times.

Were any of these three scenarios to come to pass then tighter fiscal policy – perhaps more likely through tax rises rather than spending cuts – would be required if borrowing is to be brought back onto its pre-crisis trajectory.