Book

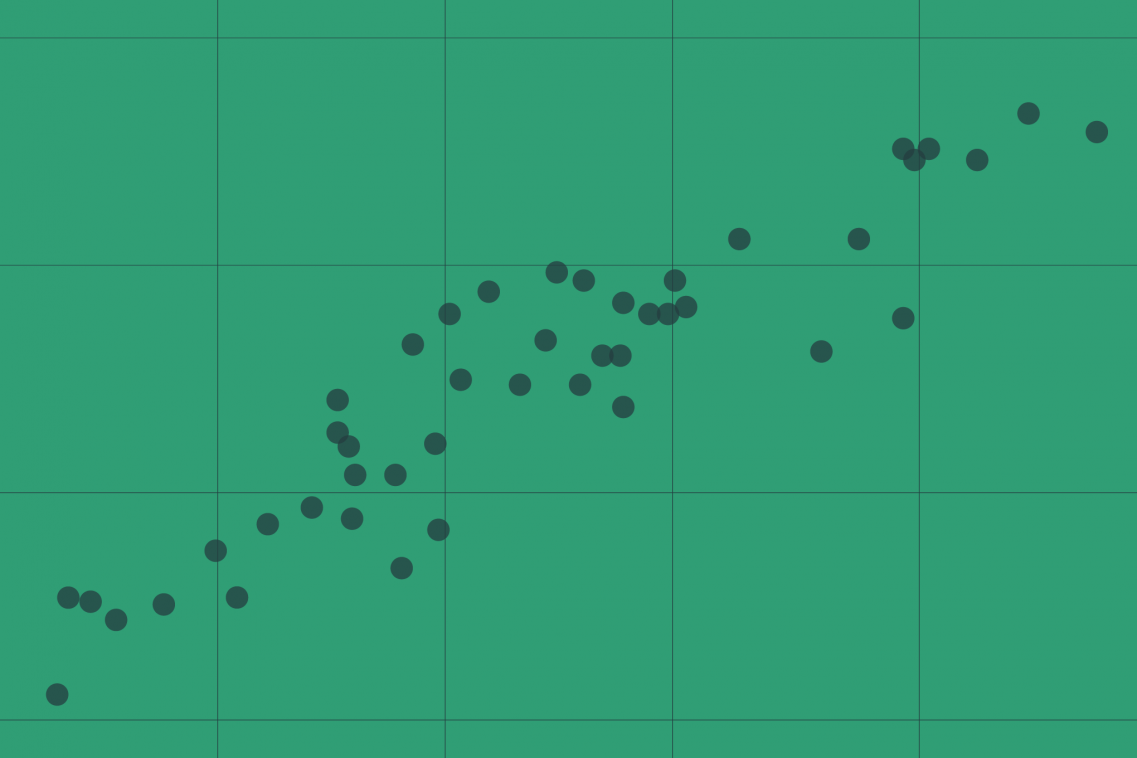

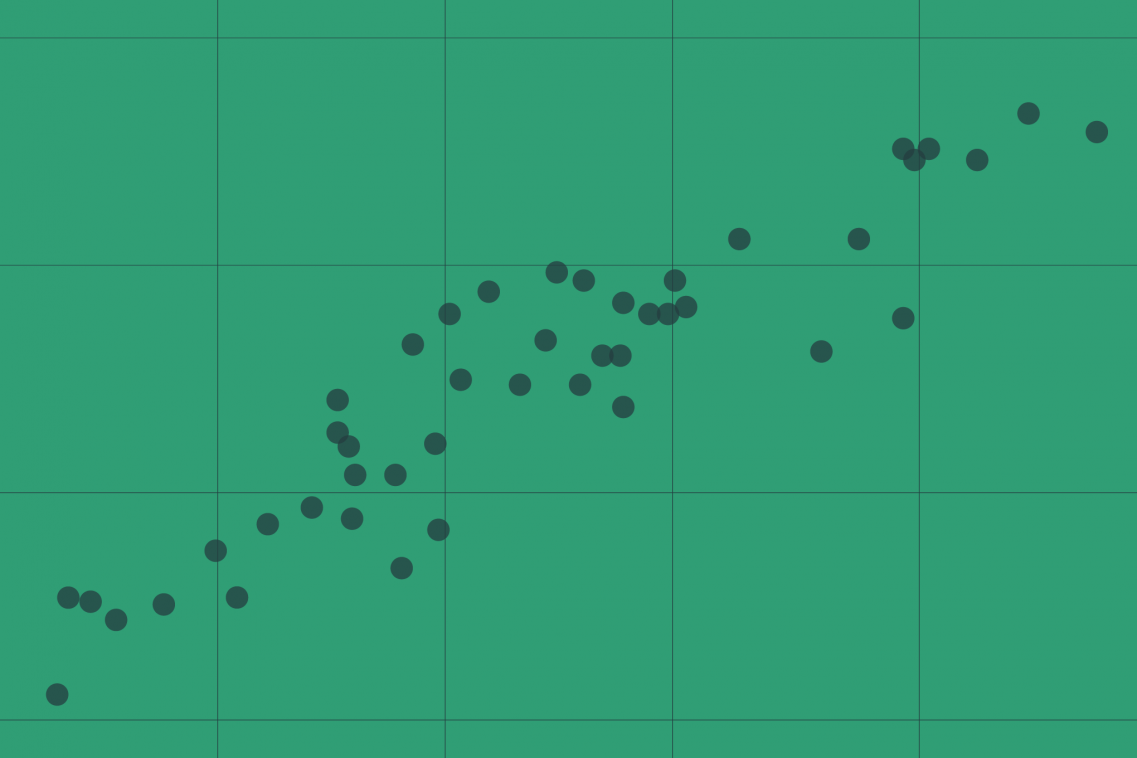

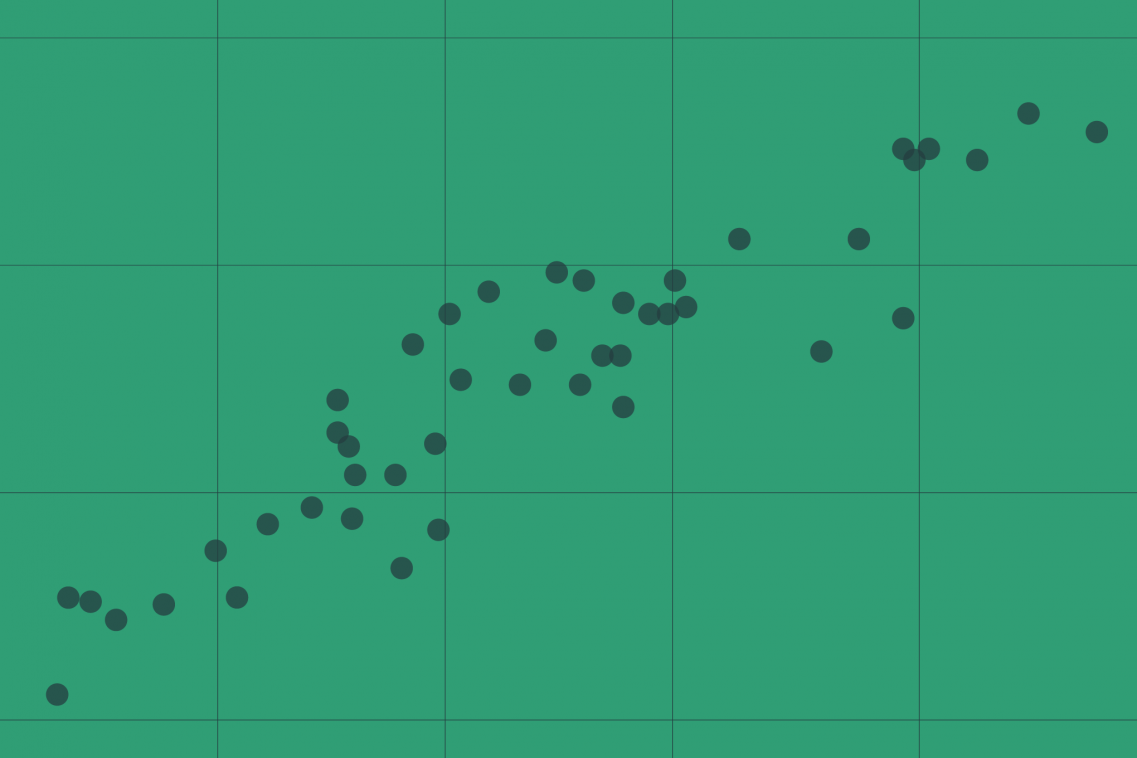

This book examines how family background determines university success, analyses who goes to university, who does best at university once they are there, and who succeeds in the labour market following graduation, and looks at the impact of the 2006 and 2012 tuition fee increases.