The upcoming Spending Review follows a decade of austerity and unprecedented new financial pressures and service responsibilities for councils as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. The pandemic has pushed up councils’ spending and reduced their local revenues, with the UK and devolved governments having to provide substantial top-ups to councils’ grant funding over the last 18 months to help them weather this storm. Some of these pressures are likely to persist, and will come on top of underlying increases in the demand for and cost of council-provided services. And a range of reforms to councils’ funding arrangements and responsibilities are set to take effect over the next few years – or should be considered by the UK and devolved governments.

We examine what’s happened and what’s next for councils in England and Wales, focusing on the short-term financial impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, the medium-term financial outlook, and planned and potential financial and service reforms over the next few years.

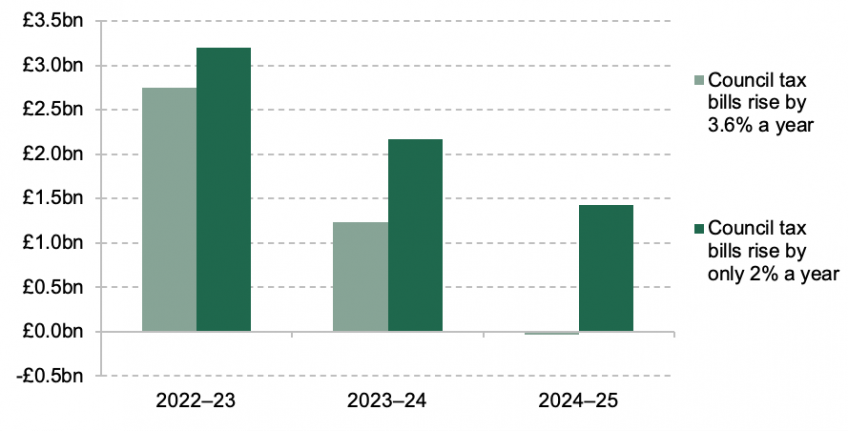

Potential funding gap facing English councils each year (£ billion)

Note: Projected spending required to maintain 2019–20 service levels, less projected revenues, under different scenarios for allowed increases in council tax bills. Grant funding from government is assumed to grow in line with average for ‘unprotected’ departments. For full details, see Table 7.2 and the Online Spreadsheet Appendix to Chapter 7.

Keyfindings

- Driven by cuts in central government funding, English councils’ non-education spending per resident fell by almost a quarter in real terms between 2009–10 and 2019–20. Most of this cut was in the early part of the 2010s, when deep cuts to grant funding were combined with a cash-terms council tax freeze. The lack of a council tax freeze in Wales, as well as smaller cuts to grant funding and Welsh councils using their ability to shift funding from education budgets, means that Welsh councils’ non-education spending per resident fell by more like a tenth over the decade.

Impact of the pandemic

- Overall, the £10.4 billion in additional funding provided by the UK government more than compensated English councils for their estimated in-year COVID-19-related financial pressures in 2020–21. However, most funding was provided on the basis of relatively rough, up-front needs assessments, and councils were only partly compensated for losses in their incomes, which varied widely. As a result, underlying the aggregate ‘over-compensation’, many councils, and particularly shire district councils, were ‘under-compensated’. In contrast, the Welsh Government provided most funding on the basis of ex-post claims from councils, which channelled more money to those councils that reported the greatest financial impacts, but could have reduced their incentives to control costs and generate income.

- Additional funding is also being provided to councils in 2021–22 to help address the pandemic – but the funding announced so far will likely be insufficient to meet the COVID-related pressures. In England, around £3.8 billion has been provided to meet higher expenditures and non-tax income losses, but councils forecast that such pressures amounted to £3.2 billion in the first half of the year alone. We estimate that English councils could face a shortfall in their COVID-19 funding this year of £0.7 billion. This suggests the government will likely have to provide English councils with additional funding for the second half of this financial year. The Welsh Government will also likely have to extend its COVID-19 financial pressures compensation scheme, which expired at the end of September.

Medium-term outlook

- The COVID-19 pandemic is likely to continue to affect councils’ spending and income-generating capacity over the next few years. Even as these pressures (hopefully) abate, councils will still face underlying growth in service demands and costs. Under our central projections, English councils would need a £10 billion increase in revenues between 2019–20 and 2024–25 to maintain service levels. If grant funding for councils moves in line with what current overall spending plans imply, council tax increases of 3.6% a year would be needed to close the funding gap across the sector as a whole by 2024−25, increasing the average council tax bill by £160 (£77 in real terms) over the next three years. However, councils will likely face large funding gaps over the next two years without additional grant funding – unless COVID-19-related spending pressures almost entirely abate by the end of this year. And uncertainty about the financial outlook is significant, with more of a risk of higher pressures than lower pressures, not least due to the potential for further significant disruption and long-term impacts from COVID-19.

- This uncertainty means that setting firm plans for council funding for the next three years is an impossible task. Instead, the Chancellor and DLUHC should consider setting a baseline amount of funding (plus principles for council tax increases), with a commitment to top this up in later Budgets (or even between Budgets) if necessary. That would allow councils to plan spending on their core services with some degree of certainty, provide them with a degree of assurance that funding will be forthcoming to deal with future COVID-19 surges and potential lockdowns, and minimise the risk of ‘locking in’ funding that may not actually be needed if COVID-19 pressures abate.

Reforms to funding, and devolution

- England – unlike Wales – also lacks an up-to-date and coherent system for assessing how much different councils need to spend and how much they can raise themselves via local taxes. For instance, the allocation of social care funding this year was still based on local populations in 2013. Yet since then, there have been dramatic changes in population: for example, the population of Tower Hamlets has grown by 21%, compared with a 2% decline in Blackpool. The repeatedly delayed ‘fair funding review’ aims to address this and should be completed. Numerous important decisions on the specifics need to be taken separately from the Spending Review, but it will be easier to transition to the new system if the Chancellor greases the wheels with additional funding given the potential large cuts some councils could otherwise face. A sensible outcome to the fair funding review would have advantages for the Treasury: by making it easier to target grant funding where it is most needed, it would help reduce the total amount that would need to be provided to councils in future fiscal events.

- Council tax also needs to be revalued and reformed, which could contribute to the government’s levelling-up agenda, by ending the current situation where poorer households and poorer parts of the country face taxes that are much higher shares of their properties’ values. Unfortunately, the UK government seems to have set itself against reform. The Chancellor should use the opportunity of the Spending Review to at least signal a willingness to reverse this short-sighted decision. If he does not, England could be left behind by Wales and Scotland where welcome reforms to council tax are definitely on the agenda.

- The UK government has signalled its desire to agree more devolution deals with English councils, with a particular focus on the shire county areas of England that have largely missed out on devolution so far. To help ensure both voters and the Whitehall machinery understand the division of powers in different parts of England, the government should develop a number of devolution ‘packages’ rather than have completely bespoke arrangements for each area, and ensure there is a straightforward and up-to-date central hub for information on what is devolved where.

Social care

- Perhaps the most significant upcoming reforms for English councils are those planned for the adult social care system. These include a more generous means test, a lifetime cap on the costs people may have to pay privately, and a new right for those paying privately to have their council organise their care – and pay the lower rates councils negotiate with providers. The £5.4 billion of funding the government is providing over the next three years to help roll out these reforms is unlikely to be sufficient to deliver its ambitions in full.

- By the second half of the 2020s, the reforms could require up to an additional £5 billion every year. The proposals also leave unaddressed several other concerns with the current adult social care system – including low pay levels for social care workers, and highly stringent needs assessments, which contributed to large falls in the numbers deemed to need social care services in the 2010s. Addressing these issues too would cost billions more per year, and adult social care is likely to remain a financial headache for councils and the Chancellor for years to come.