On Tuesday 13 March the Chancellor Phillip Hammond will present the first Spring Statement to Parliament.

While he has reserved the right to announce new measures in the Spring Statement “if the economic circumstances require it” these are not expected. If this is kept to – in this and future years – then Mr Hammond should be commended rather than criticised as we should not have two fiscal events every year. But the precedents here are not good: Gordon Brown’s first Pre-Budget Report in 1997 and George Osborne’s first Autumn Statement in 2010 both contained very few measures, but neither Chancellor subsequently managed to resist the temptation to have two full-blown fiscal events each year.

Mr Hammond should have some good fiscal news to announce. In November the OBR revised down its forecast of borrowing this year from £58 billion to £50 billion. Stronger than expected tax receipts since then mean that should come down further and will probably come in below the £46 billion borrowed last year. If, as is just possible, borrowing comes in below £41 billion this financial year (and we spent that amount on investment, as planned) then we would see a surplus on the current budget – i.e. the amount being borrowed will be less than the amount of spending which counts as investment, or capital, spending. Such a surplus has not been achieved in the UK since 2001–02.

While borrowing has broadly returned to pre-crisis levels, and has come down very sharply from 10% of national income peak in 2010–11, public debt, at around 86% of national income, is more than twice as high as it was pre-recession and at its highest level since 1965–66.

The improvement in public finances this year reflects strength in tax receipts. Income tax revenues have been strong, largely driven by self-assessment receipts, which based on the January numbers imply a stronger full-year out-turn than forecast. Corporation tax receipts look set to be revised up again as corporate profits continue to exceed OBR expectations. Receipts of stamp duty on property transactions have also been strong in recent months. However, the fall in the forecast borrowing in future years could be smaller than that for 2017–18 for at least three reasons:

- First, some of the strength in receipts this year may represent a one-off boost rather than something that can be expected to recur in future years. For example self-assessment receipts in January were not as weak as implied by the OBR’s forecast, but some of this could reflect revenue that was previously expected to be received in future years.

- Second, the market expectation is now that interest rates will rise more quickly than thought in November. The way that the Bank of England’s programme of quantitative easing is scored means that debt interest spending is highly sensitive to this, and is likely to be revised up by £1 billion to £1½ billion a year in the early 2020s as a result.

- Third, the Government announced in January that it would not appeal a High Court decision reversing recent changes to the Personal Independence Payments rules affecting some who find it hard to make journeys due to experiencing overwhelming psychological distress. The Department for Work and Pensions has provided an early estimate that this ruling will benefit around 220,000 individuals at a cost over five years of £3.7 billion.

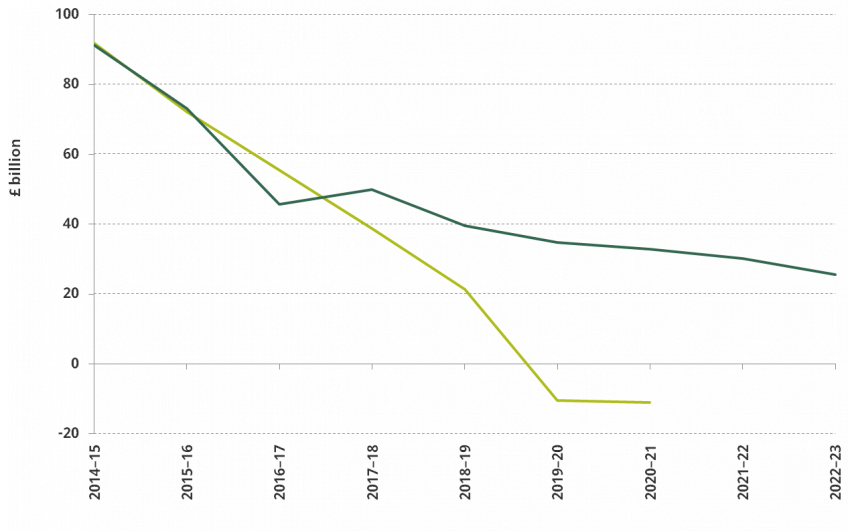

Even so Mr Hammond will probably be able to point to lower forecast borrowing over the next five years than expected in November. But before the champagne corks start popping it is worth comparing the latest borrowing forecasts to those made just two years ago. Then Mr Osborne, as Chancellor, was forecasting that we would have a surplus of £10 billion in 2019–20, in line with his commitment to have eliminated the deficit by that point. As shown in the Figure below, the fiscal forecasts have deteriorated quite dramatically since then, with the November forecast being for the UK government still to be running a deficit of £26 billion in 2022–23. A large part of this deterioration was ascribed by the OBR in 2016 to the likely effects of the decision to leave the European Union. A subsequent downwards revision occurred in November 2017 as the OBR downgraded forecast productivity growth in the light of the UK’s dismal performance over the last seven years.

So, the welcome modest improvement in the outlook for the public finances expected on Tuesday will still leave us looking at a much bigger deficit than expected in March 2016.

Deficit forecasts: March 2016 and November 2017 compared

Source: Office for Budget Responsibility.

New policies in the pipeline

We may not get any new announcements on Tuesday but there are plenty of new policies coming into effect this April. Motorists will benefit from yet another freeze in fuel duties, while many receiving a large inheritance will benefit from a further £25,000 increase in the main residence allowance within inheritance tax. Tax rises will hit those with more than £2,000 of dividend income, those buying sugary soft drinks, and those with mortgages on buy-to-let properties.

There are also significant public spending cuts still in the pipeline. For example spending by the Ministry of Justice is intended to fall by 16% over the next two years. This may not prove easy to deliver in the context of a stable prison population and growing problems within prisons. The NHS budget is not being cut: but after accounting for economy-wide inflation and growth in the population it is broadly flat, which will continue to be very challenging given population ageing and other pressures on the health service.

Of most immediate consequence for some households is the large package of benefit cuts announced by Mr Osborne after the 2015 general election. Additional cuts will continue to affect the lowest income half of working age households adversely. These include:

- The third year of the four year freeze to the rates of most working age benefits. This will be much the most painful freeze so far. Inflation in September 2015 and September 2016 was very low, so inflation uprating would have implied an increase of just 1% over April 2016 and April 2017 combined. By contrast inflation has been much higher recently and benefits would have increased by 3% this April to compensate for price rises. The saving to the government, and cost to households, of the freeze this year alone is over £2 billion.

- No longer paying a higher-rate of tax credit for new first children (a loss of up to £545 for a household), or paying additional means-tested benefits for most new third or subsequent children (a loss of up to £2,780 per extra child), which was first introduced in April 2017, will affect more families.

- Universal credit, which on average is less generous than the system of legacy benefits that it is replacing, continues to be rolled out across the UK. Some of the biggest losers relative to the legacy system include those who own their own home, families with significant amounts of unearned income or financial assets and low-income self-employed individuals.

Finally Mr Hammond has said that Spring Statement will “consider longer-term fiscal challenges and start consultations on how they can be addressed”. There are many potential topics that he could consult on. These include: how should we confront the public finance challenges posed by an ageing population, how should the tax system be reformed in the light of trends such as the growth in the ‘gig economy’ and the shift to electric vehicles, and many others. Which issues – if any – the Chancellor chooses to start a consultation on could be the most important part of Tuesday’s announcement.

Notes

On Wednesday 14 March, the day after the Spring Statement, IFS researchers will present their analysis of the public finances, putting them in the context of recent trends, and will discuss economic challenges facing the country. They will also respond to any announcements on policy made by the Chancellor and set out the impact of measures set to come into force this April. You can register to attend here.