Paul Johnson (IFS Director)

Well, yesterday’s Spring Statement certainly met the Chancellor’s objective of not constituting a fiscal event. We should not complain. One fiscal event a year is plenty.

And under the circumstances, coming as it did right in the middle of the votes on Brexit, which will play such a central role in determining the path of the economy over the coming years, it is unsurprising that Mr Hammond did not make any big fiscal decisions. Indeed, by once again declining to set totals for the forthcoming spending review, he deferred making some of the biggest non Brexit decisions of the parliament.

For that spending review, which we now know is planned to cover three years from 2020-21, will determine whether austerity really has ended and whether spending on public services will finally start to move decisively upwards after nearly a decade of unprecedented cuts.

There are some clues as to where we might end up going with the spending review, assuming Brexit goes somewhat as planned.

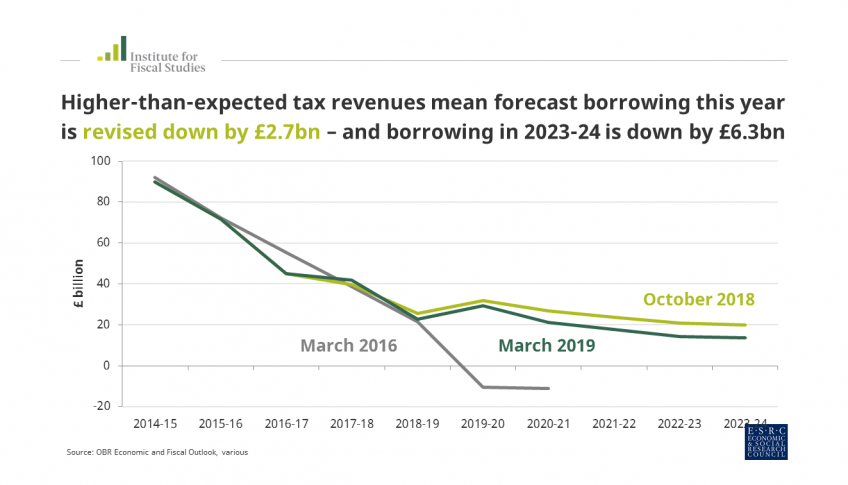

The public finances again surprised on the upside, with forecasts improving even on the big gains we saw back in October. Borrowing is set to come in at just £23 billion this year. At 1.1% of GDP that’s its lowest level since 2001-02. It is £14 billion less than forecast just a year ago. On current forecasts, it will remain low, and within the Chancellor’s fiscal target of a deficit below 2% of national income in 2020-21, for the next few years.

Note, though, that this improvement in the public finances comes in part on the back of a widening in the earnings distribution. The OBR notes that the most recent Real Time Information suggests that pay of the top 0.1% has been rising considerably faster than the average over the last year or more – something which was not true for most of the period after 2010.

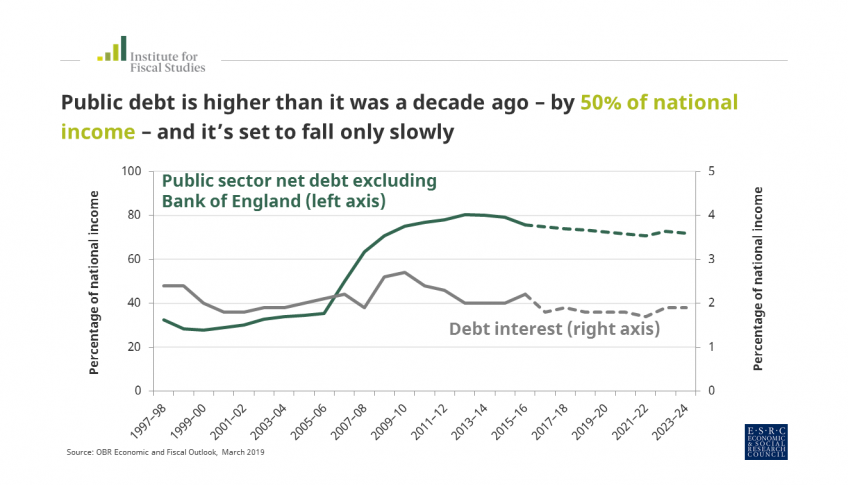

Assuming that he is not fiercely wedded to a target of balancing the books completely by the mid 2020s – and the evidence doesn’t suggest he is – then he probably would have room to find a reasonable amount of extra cash for the spending review period. Even an extra £15 billion a year on top of current plans could keep borrowing within that 2% of GDP limit, and keep debt falling as a fraction of national income – albeit slowly. Extra spending of that sort would, finally, allow the Chancellor to say with rather more conviction that austerity really was coming to an end. It would mean spending rising not just overall in real terms, but even for “unprotected” departments, and as a fraction of national income.

Of course if things go wrong with Brexit – or indeed for other reasons – then that headroom could be removed. Remember that the OBR forecasts are all predicated on a fairly smooth transition, certainly not on crashing out of the EU without a deal. That would lead to lower growth and hence a fiscal cost.

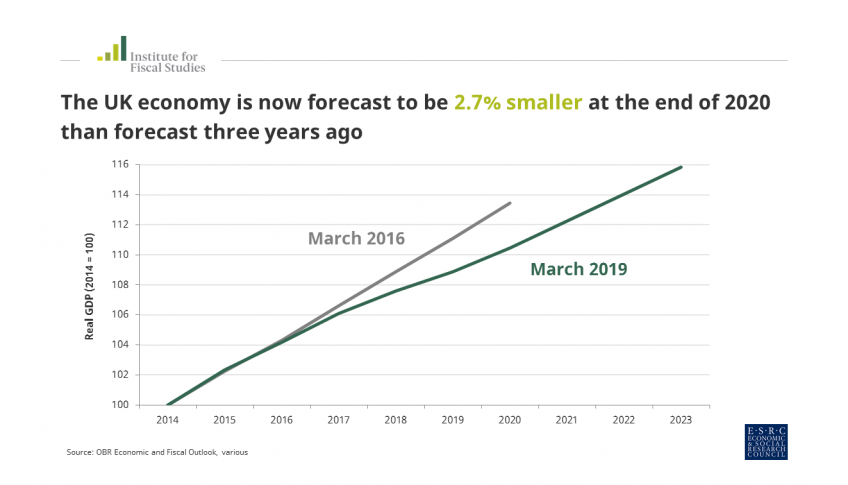

And don’t forget the context. The deficit is lower than forecast a year ago, but still higher than forecast in March 2016: £32 billion higher in 2020–21. There is a consensus that the economy would have been about 2% bigger had the Brexit vote not occurred. In those circumstances the deficit would have been smaller still and the fiscal room for manoeuvre greater. The end of austerity could already have been rather more decisively with us.

Challenges

One would usually see a small scale Spring Statement as a bit of a relief. But perhaps less so than usual right now because it comes off the back of a series of rather small scale fiscal events, at least in terms of really looking to address some of the big challenges we face. One of the costs of a combination of the obsessive focus on Brexit and the lack of parliamentary majority has been the lack of focus on some of these challenges.

The one new announcement which might help guide policy related to the National Living Wage. And that was an announcement of a review rather than of a new policy. But a review is the right way forward here. The current policy, to move the NLW to 60% of median earnings by 2020, is already ambitious by UK and international standards. Going further, as Mr Hammond intimated he would like to do, should happen only following a thorough review of the evidence of its likely effect – though the fact that current UK policy will already take it towards the top of the international league table for the level of its minimum wage may make convincing evidence on the effects of further increases hard to gather.

Beyond that neither this Spring Statement nor other recent fiscal events have paid a lot of heed to challenges coming our way.

Despite the obvious importance and urgency of the issue, waiting for the Social Care Green Paper has become rather like “Waiting for Godot”, perhaps appropriately subtitled “a tragicomedy in two acts”. It didn’t even merit a mention. The Augar review of funding further and higher education was at least acknowledged, though we still await its conclusions.

Any news of funding for other public services will await the spending review. Local government, prisons, the social care sector, and others will need to continue to cope, as evidence of their current struggles becomes increasingly clear.

There was no reprieve announced for the millions of working age families dependent on benefits. The fourth year of the benefit freeze is going ahead. 10 million families will have lost an average of £420 a year as a result of the freeze. Ignoring those only affected by the child benefit freeze, 7 million poorer families will have lost an average of £560 apiece. At the same time the benefit system is facing mounting challenges from increasing in work poverty, increasing numbers with disabilities, and a growing impact from high levels of private renting.

2020 will see another change presaging further challenges. For the first time in a decade the number of people over state pension age will start to rise – by 1.2 million in six years – as rises in the female and male state pension ages pause. If total spending doesn’t rise as a fraction of national income we are now perhaps only 20 years from the moment when half of all state spending goes on just health, pensions and social care. It was 30% at the turn of the century.

But given the difficulties facing other public services, a world in which we spend less on them to accommodate increased spending on health and pensions, looks hard to envisage. So what about the taxation side of the balance sheet?

Well tax is currently at its highest sustained level as a fraction of national income since the early 1950s. Further increases would not take us outside international experience – many countries raise more in tax than we do – but it would take us further from our own experience.

And the tax system faces a number of big challenges in any case.

There is the ongoing worry over the taxation of multinationals and digital companies; there is the growing numbers of owner managers and the self employed, who pay less tax than equivalent employees; the continued failure to maintain the real value of fuel duties. And perhaps equally worrying is the apparent presumption in some quarters that if we do want more revenue it can all come from the rich and from companies. It can’t. That’s not how other countries do it.

There’s plenty that needs fixing and there are ways of raising more revenue, but they need to be carefully thought out and implemented if they are to be both effective and fair.

To conclude

So, Brexit matters, but it isn’t the only thing that matters. The need for an effective spending review, taking account of the public finance situation and the needs of public services, is urgent. Longer term challenges cannot be ignored forever. Some of them are quickly becoming very near term challenges. Getting policy right on welfare, pensions, public spending and tax will matter to us all and will require a lot more focus and attention from government than they seem to be getting.