The global outlook and recent trends in the UK economy point to significant headwinds for growth going forwards. Arguably the most important determinant of the UK’s economic trajectory will be the continuing process of leaving the European Union. Brexit no longer ‘just’ determines future relations with the UK’s largest trading partner and the transition towards them. It has become intertwined with the political outlook and thus broader economic policies, including monetary policy.

At the time of writing, Prime Minister Boris Johnson’s government has failed to break both the deadlock in negotiations with the EU over the arrangements at the Northern Irish border and the deadlock in parliament over the UK’s wider Brexit strategy. This has left the UK with little clarity on when, how or even whether it will leave the European Union. And, with the increasing chances of a general election in the coming months, the Brexit stance and domestic agenda of the UK’s opposition parties would become relevant to growth in some plausible scenarios.

In this chapter, we set out forecasts for the UK economy under four distinct Brexit scenarios: continued uncertainty (our base case); a no-deal scenario accompanied by significant fiscal loosening; a negotiated Brexit deal passed through the current parliament; or a second referendum on a Brexit deal negotiated by a Labour-led coalition, culminating in a vote to remain. In each case, the impacts on the economy will depend not just on relationships with Brussels, but also on policy decisions made in Westminster.

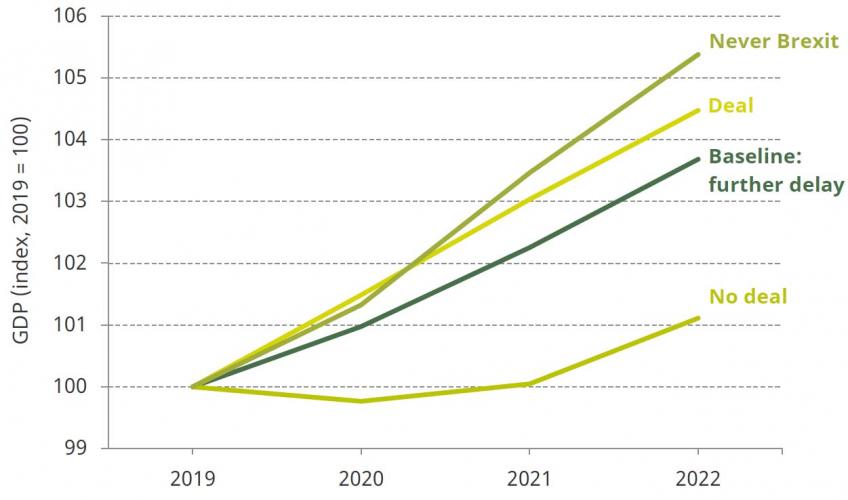

We find that a ‘no-deal’ Brexit makes for the hardest hit to the economy under these scenarios. By contrast, our scenario for ‘no Brexit’ – which involves a Labour-led coalition government that brings in significant tax and spending giveaways but does not implement all of the more radical structural reforms outlined in Labour’s 2017 manifesto – would, at least for the next three years, provide the most optimistic outlook for growth.

Real GDP growth in the UK under different Brexit scenarios (2019 = 100)

Key findings

- Whether – and if so how and when – the UK leaves the European Union will be perhaps the key determinant of growth over the next few years. Obviously, Brexit will define the terms on which the UK trades with its largest trading partner. But different Brexit outcomes may also be tied to different political outcomes in Westminster, and these come with very different sets of domestic policies that would significantly affect the economy.

- In our base scenario, the UK continues to delay Brexit. In this scenario, we assume a further fiscal loosening of between 1 and 2% of GDP. There would be a chance of small rate cuts. Growth remains below 1% in 2020 and, while it then picks up, it remains very poor, below 1½% in 2021 and 2022.

- Securing a Brexit deal would be better for the economy over the next two to three years than another delay. If this were to come with tax cuts and further spending increases together worth 1 to 1½% of GDP (over and above the loosening at the September 2019 Spending Round), then growth should pick up to (a still poor) 1½% a year in the short term. Some pent-up investment should occur, and consumer confidence would improve, as the risk of a no-deal Brexit recedes.

- A ‘no-deal’ Brexit would be economically considerably worse, even under a relatively benign scenario. We assume this would happen under a Conservative-led government, which would implement further fiscal loosening totalling 2% of GDP. Interest rates are cut to zero alongside £50 billion of quantitative easing. Private consumption and investment growth falls while net trade is also a drag on growth. Overall, the economy does not grow over the next two years, and grows by just 1.1% in 2022, leaving it 2½% smaller in that year than under our base case.

- Revoking Brexit would lead to the best economic outcome. We assume this would require a Labour-led government which, as well as revoking Brexit, would also implement significant tax and spending increases, an overall fiscal loosening and some tightening of labour market regulations. Interest rates would also rise more quickly. This might result in growth of 2% a year. Crucially, this scenario involves a Labour-led coalition rather than a majority Labour government.

- In the short term, implementation of the full 2017 Labour manifesto would offset at least some of the economic benefits of remaining in the EU. Widespread nationalisations, handing 10% of share capital of large companies to employees while redirecting some dividends to the Treasury, or other policies that might reduce private sector investment significantly, would challenge the UK’s traditional ‘business model’ and risk damaging growth by an amount it is not possible to quantify. Unlike Brexit, at least some of these policies will be reversible under future governments.