Ross Campbell is Director, Public Sector at the Institute of Chartered Accountants in England and Wales (ICAEW) and Martin Wheatcroft is a Fiscal Accountant and the Managing Director of Pendan Fiscal Analysis.

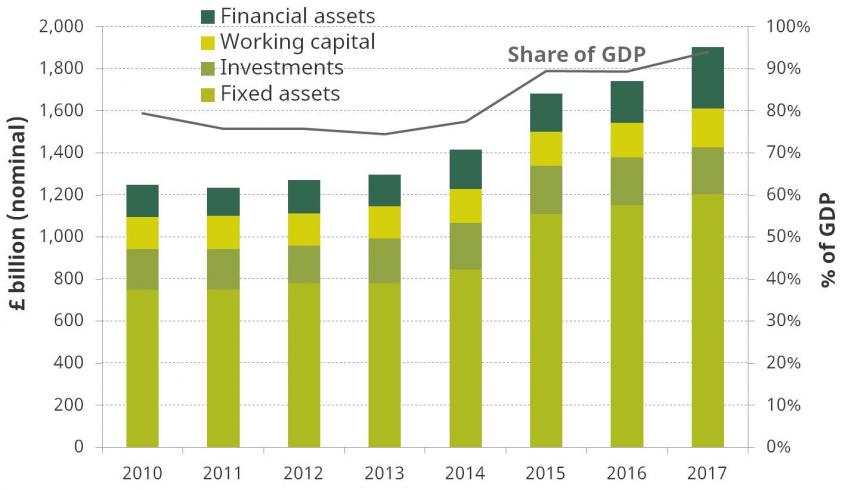

Public assets are integral to both the government’s balance sheet and the functioning of the UK. Some of these assets, such as schools and hospitals, are essential in delivering public services. Others, such as the road network, are part of the economic, social and legal infrastructure that supports economic activity and hence the tax revenues needed to pay for public services.

The government is undertaking a Balance Sheet Review, considering how it can use public assets in the most effective way to advance its policy priorities, and how it manages its liabilities and other financial commitments. In advance of the progress report expected with the 2018 Autumn Budget, this chapter provides an overview of the assets owned by the UK public sector and discusses how the Balance Sheet Review can be used to improve the utilisation of public assets and the prospects for a comprehensive investment and asset management strategy.

Key findings

- HM Treasury is conducting a Balance Sheet Review that is due to report alongside the 2018 Autumn Budget. This provides an opportunity to develop a comprehensive investment and asset management strategy, going beyond ad hoc initiatives such as the recent establishment of the Government Property Agency to improve the management of offices and other general-purpose central government property.

- Public sector assets are less than half the size of public sector liabilities. At 31 March 2017, the government reported assets of £1.9 trillion (94% of national income), compared with total liabilities of £4.3 trillion (214% of national income). Most public sector assets are not readily saleable and could not easily be used to settle liabilities, although the public sector’s most significant resource – the ability to levy taxes – is excluded.

- Capital investment is a relatively small component of public spending and has declined since 2009–10, although the government plans to increase investment next year and the year after. Capital expenditure in 2016–17 of £55 billion (2.8% of national income) was less than 7% of non-capital expenditure of £819 billion (41.2% of national income) and 9% lower in real terms than in 2009–10. Net additions to fixed assets after depreciation and disposals were just £18 billion (0.9% of national income).

- The government is reliant on future tax revenues to fund its financial commitments, with public debt currently standing at close to £2 trillion. There are no social security or social care funds. No money has been set aside for £1.9 trillion in unfunded public service pensions, nuclear decommissioning or clinical negligence liabilities.

- Labour party proposals for nationalisation would add to public sector assets, but the borrowing required would add considerably to liabilities. Higher revenues would follow, but there is a risk of underinvestment in the future without a change in capital allocation approach. Nationalising utilities, train operations, the Royal Mail and PFI contracts could potentially increase public debt by more than £200 billion.

Figure. Total assets, March 2010 to March 2017 (£ billion and % of GDP)

Source: HM Treasury, Whole of Government Accounts 2016–17 and earlier years.